31 October 2025

Behold.

Wyeth, Witch Country, Cushing, 1973

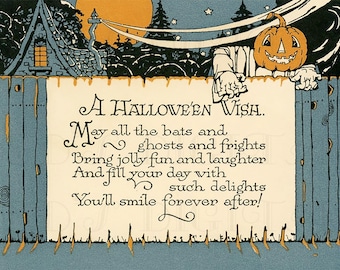

Out I went into the meadow,

Where the moon was shining brightly,

And the oak-tree’s lengthening shadows

On the sloping sward did lean;

For I longed to see the goblins,

And the dainty-footed fairies,

And the gnomes, who dwell in caverns,

But come forth on Halloween.

“All the spirits, good and evil,

Fay and pixie, witch and wizard,

On this night will sure be stirring,"

Thought I, as I walked along;

“And if Puck, the merry wanderer,

Or her majesty, Titania,

Or that Mab who teases housewives

If their housewifery be wrong,

Should but condescend to meet me”—

But my thoughts took sudden parting,

For I saw, a few feet from me,

Standing in the moonlight there,

A quaint, roguish little figure,

And I knew ‘twas Puck, the trickster,

By the twinkle of his bright eyes

Underneath his shaggy hair.

Yet I felt no fear of Robin,

Salutation brief he uttered,

Laughed and touched me on the shoulder,

And we lightly walked away;

And I found that I was smaller,

For the grasses brushed my elbows,

And the asters seemed like oak-trees,

With their trunks so tall and gray.

Swiftly as the wind we traveled,

Till we came unto a garden,

Bright within a gloomy forest,

Like a gem within the mine;

And I saw, as we grew nearer,

That the flowers so blue and golden

Were but little men and women,

Who amongst the green did shine.

But ‘twas marvelous the resemblance

Their bright figures bore to blossoms,

As they smiled, and danced, and courtesied,

Clad in yellow, pink and blue;

That fair dame, my eyes were certain,

Who among them moved so proudly,

Was my moss-rose, while her ear-rings

Sparkled like the morning dew.

Here, too, danced my pinks and pansies,

Smiling, gayly, as they used to

When, like beaux bedecked and merry,

They disported in the sun;

There, with meek eyes, walked a lily,

While the violets and snow-drops

Tripped it with the lordly tulips:

Truant blossoms, every one.

Then spoke Robin to me, wondering:

“These blithe fairies are the spirits

Of the flowers which all the summer

Bloom beneath its tender sky;

When they feel the frosty fingers

Of the autumn closing round them,

They forsake their earthborn dwellings,

Which to earth return and die,

“As befits things which are mortal.

But these spirits, who are deathless,

Care not for the frosty autumn,

Nor the winter long and keen;

But, from field, and wood, and garden,

When their summer’s tasks are finished,

Gather here for dance and music,

As of old, on Halloween.”

Long, with Puck, I watched the revels,

Till the gray light of the morning

Dimmed the luster of Orion,

Starry sentry overhead;

And the fairies, at that warning,

Ceased their riot, and the brightness

Faded from the lonely forest,

And I knew that they had fled.

Ah, it ne’er can be forgotten,

This strange night I learned the secret—

That within each flower a busy

Fairy lives and works unseen

Seldom is ‘t to mortals granted

To behold the elves and pixies,

To behold the merry spirits,

Who come forth on Halloween.

Arthur Peterson

Horror-Struck.

Kelley, Just Then He Saw the Goblin Rising in His Stirrups, and in the Very Act of Hurling his Head at Him, 1991

The hair of the affrighted pedagogue rose upon his head with terror. What was to be done? To turn and fly was now too late; and besides, what chance was there of escaping ghost or goblin, if such it was, which could ride upon the wings of the wind? Summoning up, therefore, a show of courage, he demanded in stammering accents, “Who are you?” He received no reply. He repeated his demand in a still more agitated voice. Still there was no answer. Once more he cudgelled the sides of the inflexible Gunpowder, and, shutting his eyes, broke forth with involuntary fervor into a psalm tune. Just then the shadowy object of alarm put itself in motion, and with a scramble and a bound stood at once in the middle of the road. Though the night was dark and dismal, yet the form of the unknown might now in some degree be ascertained. He appeared to be a horseman of large dimensions and mounted on a black horse of powerful frame. He made no offer of molestation or sociability, but kept aloof on one side of the road, jogging along on the blind side of old Gunpowder, who had now got over his fright and waywardness.

Ichabod, who had no relish for this strange midnight companion, and bethought himself of the adventure of Brom Bones with the Galloping Hessian, now quickened his steed in hopes of leaving him behind. The stranger, however, quickened his horse to an equal pace. Ichabod pulled up, and fell into a walk, thinking to lag behind; the other did the same. His heart began to sink within him; he endeavored to resume his psalm tune, but his parched tongue clove to the roof of his mouth and he could not utter a stave. There was something in the moody and dogged silence of this pertinacious companion that was mysterious and appalling. It was soon fearfully accounted for. On mounting a rising ground, which brought the figure of his fellow-traveller in relief against the sky, gigantic in height and muffled in a cloak, Ichabod was horror-struck on perceiving that he was headless! but his horror was still more increased on observing that the head, which should have rested on his shoulders, was carried before him on the pommel of the saddle. His terror rose to desperation, he rained a shower of kicks and blows upon Gunpowder, hoping by a sudden movement to give his companion the slip; but the spectre started full jump with him. Away, then, they dashed through thick and thin, stones flying and sparks flashing at every bound. Ichabod’s flimsy garments fluttered in the air as he stretched his long lank body away over his horse’s head in the eagerness of his flight.

They had now reached the road which turns off to Sleepy Hollow; but Gunpowder, who seemed possessed with a demon, instead of keeping up it, made an opposite turn and plunged headlong down hill to the left. This road leads through a sandy hollow shaded by trees for about a quarter of a mile, where it crosses the bridge famous in goblin story, and just beyond swells the green knoll on which stands the whitewashed church.

As yet the panic of the steed had given his unskillful rider an apparent advantage in the chase; but just as he had got halfway through the hollow the girths of the saddle gave away and he felt it slipping from under him. He seized it by the pommel and endeavored to hold it firm, but in vain, and had just time to save himself by clasping old Gunpowder round the neck, when the saddle fell to the earth, and he heard it trampled under foot by his pursuer. For a moment the terror of Hans Van Ripper’s wrath passed across his mind, for it was his Sunday saddle; but this was no time for petty fears; the goblin was hard on his haunches, and (unskilled rider that he was) he had much ado to maintain his seat, sometimes slipping on one side, sometimes on another, and sometimes jolted on the high ridge of his horse’s back-bone with a violence that he verily feared would cleave him asunder.

An opening in the trees now cheered him with the hopes that the church bridge was at hand. The wavering reflection of a silver star in the bosom of the brook told him that he was not mistaken. He saw the walls of the church dimly glaring under the trees beyond. He recollected the place where Brom Bones’ ghostly competitor had disappeared. “If I can but reach that bridge,” thought Ichabod, “I am safe.” Just then he heard the black steed panting and blowing close behind him; he even fancied that he felt his hot breath. Another convulsive kick in the ribs, and old Gunpowder sprang upon the bridge; he thundered over the resounding planks; he gained the opposite side; and now Ichabod cast a look behind to see if his pursuer should vanish, according to rule, in a flash of fire and brimstone. Just then he saw the goblin rising in his stirrups, and in the very act of hurling his head at him. Ichabod endeavored to dodge the horrible missile, but too late. It encountered his cranium with a tremendous crash; he was tumbled headlong into the dust, and Gunpowder, the black steed, and the goblin rider passed by like a whirlwind.

Washington Irving, from "The Legend of Sleepy Hollow"

30 October 2025

Most.

Copley, John Adams, 1783

As good government is an empire of laws, how shall your laws be made? In a large society, inhabiting an extensive country, it is impossible that the whole should assemble to make laws. The first necessary step, then, is to depute power from the many to a few of the most wise and good.

John Adams, from "Thoughts on Government"

As good government is an empire of laws, how shall your laws be made? In a large society, inhabiting an extensive country, it is impossible that the whole should assemble to make laws. The first necessary step, then, is to depute power from the many to a few of the most wise and good.

John Adams, from "Thoughts on Government"

Reciprocal.

Among other things, you'll find that you're not the first person who was ever confused and frightened and even sickened by human behavior. You're by no means alone on that score, you'll be excited and stimulated to know. Many, many men have been just as troubled morally and spiritually as you are right now. Happily, some of them kept records of their troubles. You'll learn from them—if you want to. Just as someday, if you have something to offer, someone will learn something from you. It's a beautiful reciprocal arrangement. And it isn't education. It's history. It's poetry.

J.D. Salinger, from The Catcher in the Rye

Respectfully.

Happy Birthday, John Adams

Stuart, John Adams, 1824

I must judge for myself, but how can I judge, how can any man judge, unless his mind has been opened and enlarged by reading ... Let us tenderly and kindly cherish therefore, the means of knowledge. Let us dare to read, think, speak, and write.

29 October 2025

28 October 2025

Scourings.

Rockwell, Ichabod Crane, 1937

The schoolmaster is generally a man of some importance in the female circle of a rural neighborhood; being considered a kind of idle, gentlemanlike personage, of vastly superior taste and accomplishments to the rough country swains, and, indeed, inferior in learning only to the parson. His appearance, therefore, is apt to occasion some little stir at the tea-table of a farmhouse, and the addition of a supernumerary dish of cakes or sweetmeats, or, peradventure, the parade of a silver teapot. Our man of letters, therefore, was peculiarly happy in the smiles of all the country damsels. How he would figure among them in the churchyard, between services on Sundays; gathering grapes for them from the wild vines that overran the surrounding trees; reciting for their amusement all the epitaphs on the tombstones; or sauntering, with a whole bevy of them, along the banks of the adjacent millpond; while the more bashful country bumpkins hung sheepishly back, envying his superior elegance and address.

From his half-itinerant life, also, he was a kind of travelling gazette, carrying the whole budget of local gossip from house to house, so that his appearance was always greeted with satisfaction. He was, moreover, esteemed by the women as a man of great erudition, for he had read several books quite through, and was a perfect master of Cotton Mather’s History of New England Witchcraft, in which, by the way, he most firmly and potently believed.

He was, in fact, an odd mixture of small shrewdness and simple credulity. His appetite for the marvellous, and his powers of digesting it, were equally extraordinary; and both had been increased by his residence in this spell-bound region. No tale was too gross or monstrous for his capacious swallow. It was often his delight, after his school was dismissed in the afternoon, to stretch himself on the rich bed of clover bordering the little brook that whimpered by his schoolhouse, and there con over old Mather’s direful tales, until the gathering dusk of evening made the printed page a mere mist before his eyes. Then, as he wended his way by swamp and stream and awful woodland, to the farmhouse where he happened to be quartered, every sound of nature, at that witching hour, fluttered his excited imagination,—the moan of the whip-poor-will from the hillside, the boding cry of the tree toad, that harbinger of storm, the dreary hooting of the screech owl, or the sudden rustling in the thicket of birds frightened from their roost. The fireflies, too, which sparkled most vividly in the darkest places, now and then startled him, as one of uncommon brightness would stream across his path; and if, by chance, a huge blockhead of a beetle came winging his blundering flight against him, the poor varlet was ready to give up the ghost, with the idea that he was struck with a witch’s token. His only resource on such occasions, either to drown thought or drive away evil spirits, was to sing psalm tunes and the good people of Sleepy Hollow, as they sat by their doors of an evening, were often filled with awe at hearing his nasal melody, “in linked sweetness long drawn out,” floating from the distant hill, or along the dusky road.

Another of his sources of fearful pleasure was to pass long winter evenings with the old Dutch wives, as they sat spinning by the fire, with a row of apples roasting and spluttering along the hearth, and listen to their marvellous tales of ghosts and goblins, and haunted fields, and haunted brooks, and haunted bridges, and haunted houses, and particularly of the headless horseman, or Galloping Hessian of the Hollow, as they sometimes called him. He would delight them equally by his anecdotes of witchcraft, and of the direful omens and portentous sights and sounds in the air, which prevailed in the earlier times of Connecticut; and would frighten them woefully with speculations upon comets and shooting stars; and with the alarming fact that the world did absolutely turn round, and that they were half the time topsy-turvy!

But if there was a pleasure in all this, while snugly cuddling in the chimney corner of a chamber that was all of a ruddy glow from the crackling wood fire, and where, of course, no spectre dared to show its face, it was dearly purchased by the terrors of his subsequent walk homewards. What fearful shapes and shadows beset his path, amidst the dim and ghastly glare of a snowy night! With what wistful look did he eye every trembling ray of light streaming across the waste fields from some distant window! How often was he appalled by some shrub covered with snow, which, like a sheeted spectre, beset his very path! How often did he shrink with curdling awe at the sound of his own steps on the frosty crust beneath his feet; and dread to look over his shoulder, lest he should behold some uncouth being tramping close behind him! And how often was he thrown into complete dismay by some rushing blast, howling among the trees, in the idea that it was the Galloping Hessian on one of his nightly scourings!

Washington Irving, from "The Legend of Sleepy Hollow", found among the papers of the late Dietrich Knickerbocker in Geoffrey Crayon's Sketchbook

27 October 2025

Spread.

Boys.

And it was the afternoon of Halloween.

And all the houses shut against a cool wind.

And the town was full of cold sunlight.

But suddenly, the day was gone.

Night came out from under each tree and spread.

Ray Bradbury, from The Halloween Tree

Happy Birthday, Russell Chatham

Arriving at the creek, I entered yet another dimension, one of quiet intimacy.

The water gurgled softly over shallow riffles, but more often glided silently past watercress-lined banks. Cottonwoods grew here, but the ground was protected and quieted by dense stands of willow and wild roses, home to many cottontail rabbits which were always silently appearing and disappearing.

The fishing itself was slow and deliberate, but best of all, it was solitary. While I was kneeling by the creek, half in it, half out of it, the rest of the world ceased to exist. It was a salve that mended the soul’s tears and abrasions.

As the years passed by, my familiarity with the creek itself grew, along with a more general appreciation of the landscape of the Northern Rockies. At some point in time, perhaps seven or eight years into it, I felt an easy familiarity with the creek, and my paintings were reflecting the spirit of their motifs with an increasing accuracy.

Some have argued that fishing is merely an escape from reality. My father used to tell me I had to get used to doing things I didn’t like because that was the definition of work. I didn’t believe it when he told it to me 35 years ago, and nothing since has caused me to change my mind. The dark, silent water flowing past waving tendrils of moss, sometimes revealing the olive-colored forms of trout, is haunting. We reach out to it with our fishing rods, and by connecting ourselves to living things, we affirm that we ourselves are alive, not just in our clumsy bodies, but in our hearts and souls.

Russell Chatham, born on this day in 1939, from "The Center of Things"

26 October 2025

Sentinel.

WHAT the SCARECROW SAW

Beneath the sky where storm clouds race,

A strawman stands in tattered grace.

An old coat holds his straw-stuffed heart,

Guarding fields where shadows dart.

His burlap face, with stitches worn,

Watches seasons, weathered, torn.

Crows may laugh, yet still he sways,

Rooted firm through smoky haze.

Scarecrow, murmur, tell the tale,

Of winds that howl and rains that wail.

Point the way, through dusk and dawn,

A silent guide till night is gone.

No voice to cry, no tears to weep,

Yet dreams he holds in straw-filled sleep

Of fields alive, of skies that hum,

Of harvests reaped when Autumn's come.

Since ancient times his spirit flies,

Carried forth in brooding skies.

Scarecrow stands, both proud and meek,

Telling tales the winds bespeak.

Scarecrow, murmur, heed the breeze,

Sing of winter when all will freeze.

Through the gales hold your ground,

A silent king with a woolen crown.

Rob Firchau

Recalling.

Oh! fruit loved of boyhood — the old days recalling,

When wood-grapes were purpling and brown nuts were falling;

When wild, ugly faces we carved on its skin,

Glaring out through the dark, with a candle within.

John Greenleaf Whittier, from "The Pumpkin"

Transvaluation.

Ciseri, Ecce Homo, 1871

Naturally, also, with the death of the old mythos, metaphysics too was transformed. For one thing, while every ancient system of philosophy had to presume an economy of necessity binding the world of becoming to its inmost or highest principles, Christian theology taught from the first that the world was God’s creature in the most radically ontological sense: that it is called from nothingness, not out of any need on God’s part, but by grace. The world adds nothing to the being of God, and so nothing need be sacrificed for His glory or sustenance. In a sense, God and world alike were liberated from the fetters of necessity; God could be accorded His true transcendence and the world its true character as divine gift. The full implications of this probably became visible to Christian philosophers only with the resolution of the fourth-century trinitarian controversies, when the subordinationist schemes of Alexandrian trinitarianism were abandoned, and with them the last residue within theology of late Platonism’s vision of a descending scale of divinity mediating between God and world—the both of them comprised in a single totality.

In any event, developed Christian theology rejected nothing good in the metaphysics, ethics, or method of ancient philosophy, but—with a kind of omnivorous glee—assimilated such elements as served its ends, and always improved them in the process. Stoic morality, Plato’s language of the Good, Aristotle’s metaphysics of act and potency—all became richer and more coherent when emancipated from the morbid myths of sacrificial economy and tragic necessity. In truth, Christian theology nowhere more wantonly celebrated its triumph over the old gods than in the use it made of the so-called spolia Aegyptorum; and, by despoiling pagan philosophy of its most splendid achievements and integrating them into a vision of reality more complete than philosophy could attain on its own, theology took to itself irrevocably all the intellectual glories of antiquity. The temples were stripped of their gold and precious ornaments, the sacred vessels were carried away into the precincts of the Church and turned to better uses, and nothing was left behind but a few grim, gaunt ruins to lure back the occasional disenchanted Christian and shelter a few atavistic ghosts.

This last observation returns me at last to my earlier contention: that Christianity assisted in bringing the nihilism of modernity to pass. The command to have no other god but Him whom Christ revealed was never for Christians simply an invitation to forsake an old cult for a new, but was an announcement that the shape of the world had changed, from the depths of hell to the heaven of heavens, and all nations were called to submit to Jesus as Lord. In the great “transvaluation” that followed, there was no sphere of social, religious, or intellectual life that the Church did not claim for itself; much was abolished, and much of the grandeur and beauty of antiquity was preserved in a radically altered form, and Christian civilization—with its new synthesis and new creativity—was born.

David Bentley Hart, from "Christ and Nothing"

Sonic.

And then we heard it.

To our stunned ears, it seemed as though my parents’ bay window, situated directly behind us, had shattered to pieces. But, mysteriously, it was still there, in tact.

Our tiny nervous systems were not prepared for this sonic assault, especially because it didn’t make sense. We stared in disbelief at the window for a minute, waiting for it to spill its shards. When we got enough courage to get up and peer out the front door, we saw the lanky silhouettes of teenagers running away into the dark of the trees. Piles of dried out corn kernels were scattered all over the porch like empty shells. We had been corned.

CONNECT ... don't miss the sound file.

That sound would would make laugh so hard that I couldn't run.

Slapped.

PETA have reached out to Led Zeppelin frontman Robert Plant, and urged him to temporarily change his name to "Robert Plant Wool."

Rips.

“Mythos, in Greek,” said Borges, “is not a story that is false. It is a story that is more than true. Myth is a tear in the fabric of reality, and immense energies pour through these holy fissures. Our stories, our poems, are rips in this fabric as well, however slight.”

Jay Parini, from Borges and Me

Accessible.

van Gogh, Self-Portrait as an Artist, 1888

It certainly is a strange phenomenon that all the artists, poets, musicians, painters, are unfortunate in material things — the happy ones as well — what you said lately about Guy de Maupassant is a fresh proof of it. That brings up again the eternal question: is life completely visible to us, or isn't it rather that this side of death we see one hemisphere only?

Painters — to take them only — being dead and buried, speak to the next generation or to several succeeding generations through their work.

Is that all, or is there more besides? In a painter's life death is not perhaps the hardest thing there is.

For my own part, I declare I know nothing whatever about it. But to look at the stars always makes me dream, as simply as I dream over the black dots of a map representing towns and villages. Why, I ask myself, should the shining dots of the sky not be as accessible as the black dots on the map of France? If we take the train to get to Tarascon or Rouen, we take death to reach a star. One thing undoubtedly true in this reasoning is this: that while we are alive we cannot get to a star, any more than when we are dead we can take the train.

Vincent van Gogh, from a letter to his brother, Theo, 9 July 1888

Glaring.

Rockwell, Ghostly Gourds, 1969

The PUMPKIN

Oh, greenly and fair in the lands of the sun,

The vines of the gourd and the rich melon run,

And the rock and the tree and the cottage enfold,

With broad leaves all greenness and blossoms all gold,

Like that which o'er Nineveh's prophet once grew,

While he waited to know that his warning was true,

And longed for the storm-cloud, and listened in vain

For the rush of the whirlwind and red fire-rain.

On the banks of the Xenil the dark Spanish maiden

Comes up with the fruit of the tangled vine laden;

And the Creole of Cuba laughs out to behold

Through orange-leaves shining the broad spheres of gold;

Yet with dearer delight from his home in the North,

On the fields of his harvest the Yankee looks forth,

Where crook-necks are coiling and yellow fruit shines,

And the sun of September melts down on his vines.

Ah! on Thanksgiving day, when from East and from West,

From North and from South comes the pilgrim and guest;

When the gray-haired New Englander sees round his board

The old broken links of affection restored,

When the care-wearied man seeks his mother once more,

And the worn matron smiles where the girl smiled before,

What moistens the lip and what brightens the eye?

What calls back the past, like the rich Pumpkin pie?

Oh, fruit loved of boyhood! the old days recalling,

When wood-grapes were purpling and brown nuts were falling!

When wild, ugly faces we carved in its skin,

Glaring out through the dark with a candle within!

When we laughed round the corn-heap, with hearts all in tune,

Our chair a broad pumpkin,—our lantern the moon,

Telling tales of the fairy who travelled like steam

In a pumpkin-shell coach, with two rats for her team!

Then thanks for thy present! none sweeter or better

E'er smoked from an oven or circled a platter!

Fairer hands never wrought at a pastry more fine,

Brighter eyes never watched o'er its baking, than thine!

And the prayer, which my mouth is too full to express,

Swells my heart that thy shadow may never be less,

That the days of thy lot may be lengthened below,

And the fame of thy worth like a pumpkin-vine grow,

And thy life be as sweet, and its last sunset sky

Golden-tinted and fair as thy own Pumpkin pie!

John Greenleaf Whittier

Howling.

Kelley, Untitled, 1990

He was, in fact, an odd mixture of small shrewdness and simple credulity. His appetite for the marvellous, and his powers of digesting it, were equally extraordinary; and both had been increased by his residence in this spell-bound region. No tale was too gross or monstrous for his capacious swallow. It was often his delight, after his school was dismissed in the afternoon, to stretch himself on the rich bed of clover bordering the little brook that whimpered by his schoolhouse, and there con over old Mather’s direful tales, until the gathering dusk of evening made the printed page a mere mist before his eyes. Then, as he wended his way by swamp and stream and awful woodland, to the farmhouse where he happened to be quartered, every sound of nature, at that witching hour, fluttered his excited imagination,—the moan of the whip-poor-will from the hillside, the boding cry of the tree toad, that harbinger of storm, the dreary hooting of the screech owl, or the sudden rustling in the thicket of birds frightened from their roost. The fireflies, too, which sparkled most vividly in the darkest places, now and then startled him, as one of uncommon brightness would stream across his path; and if, by chance, a huge blockhead of a beetle came winging his blundering flight against him, the poor varlet was ready to give up the ghost, with the idea that he was struck with a witch’s token. His only resource on such occasions, either to drown thought or drive away evil spirits, was to sing psalm tunes and the good people of Sleepy Hollow, as they sat by their doors of an evening, were often filled with awe at hearing his nasal melody, “in linked sweetness long drawn out,” floating from the distant hill, or along the dusky road.

Another of his sources of fearful pleasure was to pass long winter evenings with the old Dutch wives, as they sat spinning by the fire, with a row of apples roasting and spluttering along the hearth, and listen to their marvellous tales of ghosts and goblins, and haunted fields, and haunted brooks, and haunted bridges, and haunted houses, and particularly of the headless horseman, or Galloping Hessian of the Hollow, as they sometimes called him. He would delight them equally by his anecdotes of witchcraft, and of the direful omens and portentous sights and sounds in the air, which prevailed in the earlier times of Connecticut; and would frighten them woefully with speculations upon comets and shooting stars; and with the alarming fact that the world did absolutely turn round, and that they were half the time topsy-turvy!

But if there was a pleasure in all this, while snugly cuddling in the chimney corner of a chamber that was all of a ruddy glow from the crackling wood fire, and where, of course, no spectre dared to show its face, it was dearly purchased by the terrors of his subsequent walk homewards. What fearful shapes and shadows beset his path, amidst the dim and ghastly glare of a snowy night! With what wistful look did he eye every trembling ray of light streaming across the waste fields from some distant window! How often was he appalled by some shrub covered with snow, which, like a sheeted spectre, beset his very path! How often did he shrink with curdling awe at the sound of his own steps on the frosty crust beneath his feet; and dread to look over his shoulder, lest he should behold some uncouth being tramping close behind him! And how often was he thrown into complete dismay by some rushing blast, howling among the trees, in the idea that it was the Galloping Hessian on one of his nightly scourings!

Washington Irving, from "The Legend of Sleepy Hollow"

Tradition.

Firchau, The Ancient and Sacred Rite, 1971

Tradition refuses to submit to the small and arrogant oligarchy of those who merely happen to be walking about.

G.K. Chesterton, from Orthodoxy

Happy Birthday, Domenico Scarlatti

Velasco, Domenico Scarlatti, 1738

Domenico Scarlatti, born on this date in 1685

Show yourself more human than critical and your pleasure will increase.

Domenico Scarlatti, born on this date in 1685

Basha Slavinska performs the Presto from the Sonata in A-Major, K. 24 ...

25 October 2025

Joyously.

Thomson, Nocturne, 1916

OCTOBER

October is the treasurer of the year,

And all the months pay bounty to her store;

The fields and orchards still their tribute bear,

And fill her brimming coffers more and more

But she, with youthful lavishness,

Spends all her wealth in gaudy dress,

And decks herself in garments bold

Of scarlet, purple, red, and gold.

She heedeth not how swift the hours fly,

But smiles and sings her happy life along;

She only sees above a shining sky;

She only hears the breezes’ voice in song.

Her garments trail the woodlands through,

And gather pearls of early dew

That sparkle, till the roguish Sun

Creeps up and steals them every one.

But what cares she that jewels should be lost,

When all of Nature’s bounteous wealth is hers?

Though princely fortunes may have been their cost,

Not one regret her calm demeanor stirs.

Whole-hearted, happy, careless, free,

She lives her life out joyously,

Nor cares when Frost stalks o’er her way

And turns her auburn locks to gray.

Paul Laurence Dunbar

Labels:

appreciation,

art,

Dunbar,

poetry,

poetry rules!,

Thomson

Provisions.

Wyeth, Bird in the House, 1984

- Mum's oatmeal cookies

- English walnuts, in-the-shell (a proper bowl and implements are a must)

- Usinger's braunschweiger

- Smoked scallops

- Neuske's smoked duck breast and Triple-Thick Butcher-Cut bacon

- Kern's langjaeger

- Simon Jones' Lincolnshire Poacher (essential for Fergus Henderson's Welsh Rarebit)

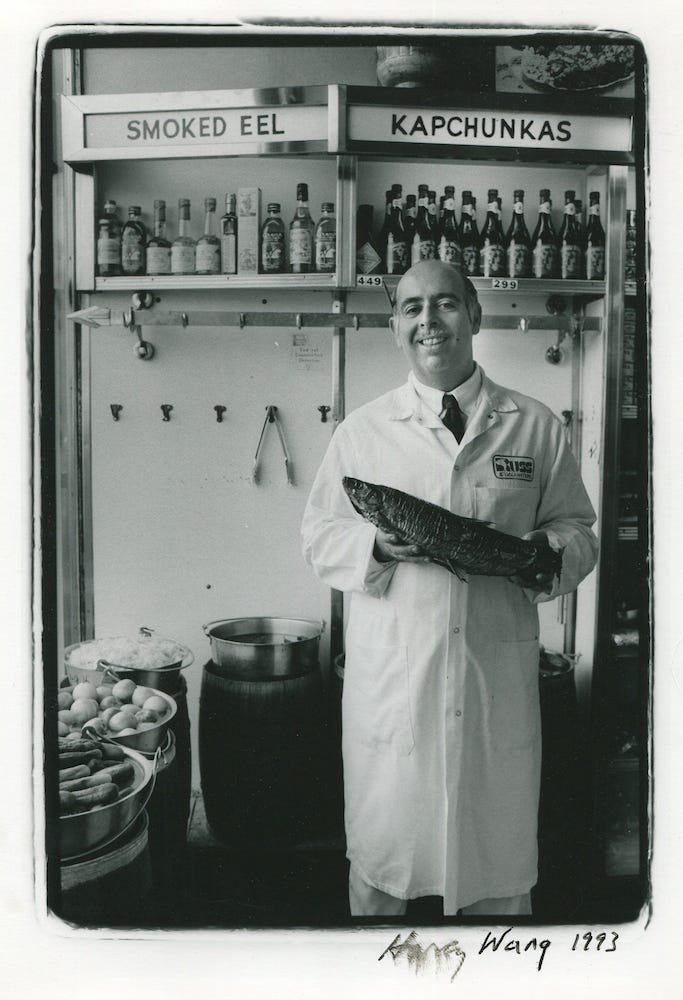

- Russ & Daughters creamed herring

- American Spoon Bloody Mary Mix

- Warre's Warrior port

- Upton Tea's Lapsang Souchong

- A selection of fine porters and stouts

- Colston-Bassett Stilton

- Manoir de Montreuil Reserve Pays d'Auge Calvados

- Laphroaig 10-Year-Old Islay Single-Malt Scotch Whisky

- Borkum Riff BourbonWhiskey pipe tobacco

- Cape Candle Bayberry Tapers

Learn.

From The Brothers Grimm tale, "The Story of a Boy Who Went Forth to Learn Fear" ...

So the sexton took him home with him, and he was to ring the church bell. A few days later the sexton awoke him at midnight and told him to get up, climb the church tower, and ring the bell."You will soon learn what it is to shudder," he thought. He secretly went there ahead of him. After the boy had reached the top of the tower, had turned around and was about to take hold of the bell rope, he saw a white figure standing on the steps opposite the sound hole."Who is there?" he shouted, but the figure gave no answer, neither moving nor stirring. "Answer me," shouted the boy, "or get out of here. You have no business here at night."The sexton, however, remained standing there motionless so that the boy would think he was a ghost.The boy shouted a second time, "What do you want here? Speak if you are an honest fellow, or I will throw you down the stairs."The sexton thought, "He can't seriously mean that." He made not a sound and stood as if he were made of stone.Then the boy shouted to him for the third time, and as that also was to no avail, he ran toward him and pushed the ghost down the stairs. It fell down ten steps and remained lying there in a corner. Then the boy rang the bell, went home, and without saying a word went to bed and fell asleep.The sexton's wife waited a long time for her husband, but he did not come back. Finally she became frightened and woke up the boy, asking, "Don't you know where my husband is? He climbed up the tower before you did.""No," replied the boy, "but someone was standing by the sound hole on the other side of the steps, and because he would neither give an answer nor go away, I took him for a thief and threw him down the steps. Go there and you will see if he was the one. I am sorry if he was."The woman ran out and found her husband, who was lying in the corner moaning. He had broken his leg. She carried him down, and then crying loudly she hurried to the boy's father. "Your boy," she shouted, "has caused a great misfortune. He threw my husband down the steps, causing him to break his leg. Take the good-for-nothing out of our house."The father was alarmed, and ran to the sexton's house, and scolded the boy. "What evil tricks are these? The devil must have prompted you to do them."

Waiting.

The fellow who invited Russell to the fete then inquired, almost as an afterthought, how he had fared that day, and when Russell said that he had caught “about 25 or so, you’d have to ask my guide”—the man just stared at him, turned, and walked off without saying another word. Russell never did hear where the party was, but the next day, fishing on his own—on the high bluff of a cutbank, the exact opposite of where most anglers would say he should have been—he hooked a big one, and ran up and down the cliff, had to go about 100 yards to land it, while some Spaniards fishing the gravel bar on the other side watched and cheered him; and afterward, they invited him over to have lunch with them, where they lay in the sun and drank good Spanish wine and ate Manchego cheese and the best jamón serrano, Russell says, that he ever had.In his studio, I get to watch him scrape down and then sand lightly a painting he’s been waiting to finish: sitting with it for days, the way a good writer will sit with an ending, even when he or she is certain. Waiting to be sure—waiting for the delightful vapors, the adrenaline fumes, of completion to wear off—and then waiting a little longer.The painting—maybe 6 inches by 9 inches—has taken him a month.

Unless.

Have I said anything I started out to say about being good? God, I don't know. A stranger is shot in the street, you hardly move to help. But if, half an hour before, you spent just ten minutes with the fellow and knew a little about him and his family, you might just jump in front of his killer and try to stop it. Really knowing is good. Not knowing, or refusing to know, is bad, or amoral, at least. You can't act if you don't know. Acting without knowing takes you right off the cliff. God, God, you must think I'm crazy, this talk. Probably think we should be out duck-shooting, elephant-gunning balloons, like you did, Will, but we got to know all there is to know about those freaks and that man heading them up. We can't be good unless we know what bad is, and it's a shame we're working against time.

Ray Bradbury, from Something Wicked This Way Comes

Treasures.

Kelley, A Fine Autumnal Day, 1990

As Ichabod jogged slowly on his way, his eye, ever open to every symptom of culinary abundance, ranged with delight over the treasures of jolly autumn. On all sides he beheld vast store of apples; some hanging in oppressive opulence on the trees; some gathered into baskets and barrels for the market; others heaped up in rich piles for the cider-press. Farther on he beheld great fields of Indian corn, with its golden ears peeping from their leafy coverts, and holding out the promise of cakes and hasty-pudding; and the yellow pumpkins lying beneath them, turning up their fair round bellies to the sun, and giving ample prospects of the most luxurious of pies; and anon he passed the fragrant buckwheat fields breathing the odor of the beehive, and as he beheld them, soft anticipations stole over his mind of dainty slapjacks, well buttered, and garnished with honey or treacle, by the delicate little dimpled hand of Katrina Van Tassel.

Washington Irving, from "The Legend of Sleepy Hollow"

Colours.

Heavy masses of shapeless vapour upon the mountains (O, the perpetual forms of Borrowdale!) yet it is no unbroken tale of dull sadness. Slanting pillars travel across the lake at long intervals, the vaporous mass whitens in large stains of light – on the lakeward ridge of that huge arm-chair of Lodore, fell a gleam of softest light, that brought out the rich hues of the late autumn. The woody Castle Crag between me and Lodore is a rich flower-garden of colours – the brightest yellows with the deepest crimsons, and the infinite shades of brown and green, the infinite diversity of which blends the whole, so that the brighter colours seem to be colours upon a ground, not coloured things.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge, from his journal dated 21 October 1803

24 October 2025

Jethro Tull-ish, "Weathercock"

Do you simply reflect changes in the patterns of the sky?

Or is it true to say the weather heeds, the twinkle in your eye?

Early.

But you take October, now. School’s been on a month and you’re riding easier in the reins, jogging along. You got time to think of the garbage you’ll dump on old man Prickett’s porch, or the hairy-ape costume you’ll wear to the YMCA the last night of the month. And if it’s around October twentieth and everything smoky-smelling and the sky orange and ash grey at twilight, it seems Hallowe’en will never come in a fall of broomsticks and a soft flap of bedsheets around corners.

But one strange wild dark long year, Hallowe’en came early.

One year Hallowe’en came on October 24, three hours after midnight.

At that time, James Nightshade of 97 Oak Street was thirteen years, eleven months, twenty-three days old. Next door, William Halloway was thirteen years, eleven months and twenty-four days old. Both touched toward fourteen; it almost trembled in their hands.

And that was the October week when they grew up overnight, and were never so young any more. . .

Ray Bradbury, from Something Wicked This Way Comes

22 October 2025

Ah.

What if you slept

And what if

In your sleep

You dreamed

And what if

In your dream

You went to heaven

And there plucked a strange and beautiful flower

And what if

When you awoke

You had that flower in you hand

Ah, what then?

Samuel Taylor Coleridge

Ideals.

"Those only deserve a monument who do not need one; that is, who have raised themselves a monument in the minds and hearts of men."

William Hazlitt, from Characteristics, in the Manner of Rochefoucauld's Maxims

The Society of Architectural Historians' recommendations, from a letter dated 16 October ...

Known as the “People’s House,” the White House is one of the most significant and visible historic properties in the country. Any project at the White House, whether it involves interior renovation, changes to the landscape, or a new exterior addition, acts as a national precedent in the treatment of historic properties. Recognizing this, we urge the White House to carefully consider our recommendations so that the project can have a positive influence on preservation practice, policies and procedures across the nation.

The National Trust for Historic Preservation responds, characteristically late ...

The federally recognized Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for Rehabilitation offer clear guidance for construction projects affecting historic properties. The Standards provide that new additions should not destroy the historic fabric of the property and that the new work should be compatible with existing massing, size, scale, and architectural features.Owned by the American people, the White House was designed by Irish architect James Hoban, whose winning proposal was selected by President George Washington. The building respects Georgian and neoclassical principles. It is a National Historic Landmark, a National Park, and a globally recognized symbol of our nation’s ideals.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

About Me

- Rob Firchau

- "A man should stir himself with poetry, stand firm in ritual, and complete himself in music." -Gary Snyder

Think ...

GASTON BACHELARD

"The house shelters day-dreaming, the house protects the dreamer, the house allows one to dream in peace.”

ARCHIVES

-

▼

2025

(1787)

-

▼

October

(151)

- Moonlight.

- Behold.

- Excellent.

- Horror-Struck.

- Excellent.

- Happy Birthday, Alfred Sisley

- Most.

- Reciprocal.

- Smile.

- Respectfully.

- No title

- Happy Birthday, John Adams

- RUSH, "Resist"

- Spooky.

- Published.

- Scourings.

- Excellent.

- Spread.

- Happy Birthday, Russell Chatham

- Sentinel.

- Recalling.

- Archibald Joyce, Autumnal Dream

- Transvaluation.

- Hallowe'en.

- After.

- Sonic.

- Slapped.

- Rips.

- Accessible.

- Holborne, "The Night-Watch"

- Glaring.

- Howling.

- Tradition.

- Happy Birthday, Domenico Scarlatti

- Joyously.

- Amontillado.

- Happy Birthday, Glenn Tipton

- No title

- Provisions.

- Learn.

- Excellent.

- Frank Sinatra, "The House I Live In"

- Kapchunkas.

- Waiting.

- Unless.

- Treasures.

- Luck.

- Visée, Prelude and Menuet en Rondeau

- Colours.

- Abolish.

- Jethro Tull-ish, "Weathercock"

- Early.

- Découpe.

- Ah.

- Ideals.

- Gallop.

- Stay.

- Nourishment.

- Countenance.

- Jethro Tull, "Songs from the Wood"

- Kapchunkas.

- Experience.

- No title

- Unimaginable.

- Happy Birthday, Samuel Taylor Coleridge

- Van Morrison, "Tore Down à la Rimbaud"

- Happy Birthday, Sir Christopher Wren

- Distance.

- Happy Birthday, Arthur Rimbaud

- Smoky-Smelling.

- Robert Plant, "The Rain Song"

- Around.

- Happy Birthday, Wynton Marsalis

- Excellent.

- Seen.

- Hello.

- Sings.

- Lobo, Versa est in luctum

- Lustreless.

- Deceived.

- AC⚡DC, "Riff Raff"

- The Cult, "Nirvana"

- Setera.

- Excellent.

- Power.

- On.

- Open.

- Sing.

- Ready.

- Excellent.

- Scratch.

- Full.

- Further.

- Happy Birthday, Friedrich Nietzsche

- Excellent.

- Happy Birthday, e.e. cummings

- Scarecrow.

- Sacred.

- Excellent.

- Vigor.

-

▼

October

(151)

CARL R. FIRCHAU (1884-1973)

"The strength of a man’s virtue should not be measured by his special exertions but by his habitual acts.” Blaise Pascal

SEARCH THIS BLOG

C.S. LEWIS

REMEMBER

SUPPORT OUR TROOPS

G.K. CHESTERTON

"Tradition refuses to submit to the small and arrogant oligarchy of those who merely happen to be walking about."

KENNETH GRAHAME

"O Mole! the beauty of it! The merry bubble and joy, the thin, clear, happy call of the distant piping!"

GEORDIE WALKER

ECHO & THE BUNNYMEN

JIM HARRISON

37. Beware, O wanderer, the road is walking too, said Rilke one day to no one in particular as good poets everywhere address the six directions. If you can’t bow, you’re dead meat. You’ll break like uncooked spaghetti. Listen to the gods. They’re shouting in your ear every second.

GIMME FIIIVE!

THE FURS

Suggestions

WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART

"When I am, as it were, completely myself, entirely alone and of good cheer – say travelling in a carriage or walking after a good meal, or during the night when I cannot sleep – it is on such occasions that my ideas flow best and most abundantly. Whence, and how, they come I know not ; nor can I force them. Those ideas that please me I retain in memory and am accustomed, as I have been told, to hum them to myself. If I continue in this way, it soon occurs to me how I may turn this dainty morsel to account, so as to make a good dish of it. That is to say, agreeable to the rules of counterpoint, to the peculiarities of various instruments etc. All this fires my soul, and, provided I am not disturbed, my subject enlarges itself, becomes methodised, and defined, and the whole, though it be long, stands almost complete and finished in my mind, so that I can survey it like a fine picture or a beautiful statue at a glance. Nor do I hear in my imagination the parts successively, but I hear them, as it were, all at once. What a delight this is, I cannot tell."

HOOKY

MARY SHELLEY

GREEN MAN

"Feel wind stir the greenwood, or turn pages of a book made from his flesh -- lean close, then, and hear, Green Man's voice."

N.C. WYETH

Cold Maker, Winter, 1909

Dick's Pour House, Lake Leelanau, Michigan

Smelt Basket

PanAm "Pacific Clipper" (1941)

JOHN SINGER SARGENT

Elizabeth Winthrop Chanler (detail), 1893

WILLIAM F. BUCKLEY JR.

SIR WINSTON CHURCHILL

"A gentleman does not have a ham sandwich without mustard."

J.R.R. TOLKIEN

"If more of us valued food and cheer and song above hoarded gold, it would be a merrier world."

JOHN MASEFIELD

"When the midnight strikes in the belfry dark/And the white goose quakes at the fox’s bark/We saddle the horse that is hayless, oatless/Hoofless and pranceless, kickless and coatless/We canter off for a midnight prowl/Whoo-hoo-hoo, says the hook-eared owl."

IKKYU

VIRGINIA WOOLF

JOHN QUINCY ADAMS

"However tiresome to others, the most indefatigable orator is never tedious to himself. The sound of his own voice never loses its harmony to his own ear; and among the delusions, which self-love is ever assiduous in attempting to pass upon virtue, he fancies himself to be sounding the sweetest tones."

SIR KENNETH GRAHAME

"Take the Adventure, heed the call, now, ere the irrevocable moment passes! ‘Tis but a banging of the door behind you, a blithesome step forward, and you are out of the old life and into the new! Then some day, some day long hence, jog home here if you will, when the cup has been drained and the play has been played, and sit down by your quiet river with a store of goodly memories for company."

JIM HARRISON

"Barring love I'll take my life in large doses alone--rivers, forests, fish, grouse, mountains. Dogs."

WILLIAM WORDSWORTH

SAMUEL ADAMS

"It is a very great mistake to imagine that the object of loyalty is the authority and interest of one individual man, however dignified by the applause or enriched by the success of popular actions."

TAO TE CHING, Lao Tzu

MARCUS AURELIUS

"Is your cucumber bitter? Throw it away. Are there briars in your path? Turn aside. That is enough. Do not go on and say, 'Why were things of this sort ever brought into this world?' neither intolerable nor everlasting - if thou bearest in mind that it has its limits, and if thou addest nothing to it in imagination. Pain is either an evil to the body (then let the body say what it thinks of it!)-or to the soul. But it is in the power of the soul to maintain its own serenity and tranquility."

VINCENT van GOGH

"What am I in the eyes of most people? A nonentity or an oddity or a disagreeable person — someone who has and will have no position in society, in short a little lower than the lowest. Very well — assuming that everything is indeed like that, then through my work I’d like to show what there is in the heart of such an oddity, such a nobody. This is my ambition, which is based less on resentment than on love in spite of everything, based more on a feeling of serenity than on passion. Even though I’m often in a mess, inside me there’s still a calm, pure harmony and music. In the poorest little house, in the filthiest corner, I see paintings or drawings. And my mind turns in that direction as if with an irresistible urge. As time passes, other things are increasingly excluded, and the more they are the faster my eyes see the picturesque. Art demands persistent work, work in spite of everything, and unceasing observation."

RICK LEACH (1975-1978)

RICHARD ADAMS

"One cloud feels lonely."

JOHN SINGER SARGENT

"Cultivate an ever continuous power of observation. Wherever you are, be always ready to make slight notes of postures, groups and incidents. Store up in the mind a continuous stream of observations."

WINSLOW HOMER

The Lone Boat, North Woods Club, Adirondacks, 1892

THOMAS BABINGTON MACAULEY

And how can man die better / Than facing fearful odds / For the ashes of his fathers / And the temples of his gods

WATERHOUSE, BOREAS, 1903

WHITE HORSES Far out at sea / There are horses to ride, / Little white horses / That race with the tide. / Their tossing manes / Are the white sea-foam, / And the lashing winds / Are driving them home- / To shadowy stables / Fast they must flee, / To the great green caverns / Down under the sea. Irene Pawsey

UMBERTO LIMONGIELLO

F. SCOTT FITZGERALD

"I don't want to repeat my innocence. I want the pleasure of losing it again.” This Side of Paradise

RALPH WALDO EMERSON

"In skating over thin ice, our safety is in our speed."

ROBERT PLANT

GARY SNYDER

"There are those who love to get dirty and fix things. They drink coffee at dawn, beer after work. And those who stay clean, just appreciate things. At breakfast they have milk and juice at night. There are those who do both, they drink tea.”

IMMANUEL KANT

"Enlightenment is man's emergence from his self-imposed nonage. Nonage is the inability to use one's own understanding without another's guidance. This nonage is self-imposed if its cause lies not in lack of understanding but in indecision and lack of courage to use one's own mind without another's guidance. Dare to know! Sapere aude. 'Have the courage to use your own understanding,' is therefore the motto of the enlightenment."

DAN CAMPBELL

"We’re gonna kick you in the teeth, and when you punch us back we’re gonna smile at you, and when you knock us down we’re going to get up, and on the way, we’re going to bite a kneecap off. We’re going to stand up, and it’s going to take two more shots to knock us down. And on the way up, we’re going to take your other kneecap, and we’re going to get up, and it’s gonna take three shots to get us down. And when we do, we’re gonna take another hunk out of you."

THOMAS HUXLEY

"Sit down before fact as a little child, be prepared to give up every conceived notion, follow humbly wherever and whatever abysses nature leads, or you will learn nothing."

JOHN DRYDEN

"Bold knaves thrive without one grain of sense, but good men starve for want of impudence.”

WILLIAM BLAKE

"Those who restrain desire do so because theirs is weak enough to be restrained."

HERMANN HESSE

"Whoever wants music instead of noise, joy instead of pleasure, soul instead of gold, creative work instead of business, passion instead of foolery, finds no home in this trivial world of ours."

GEORGE MACDONALD

"Certainly work is not always required of a man. There is such a thing as a sacred idleness, the cultivation of which is now fearfully neglected."

REV. DR. CORNEL WEST

"You have to have a habitual vision of greatness … you have to believe in fact that you will refuse to settle for mediocrity. You won’t confuse your financial security with your personal integrity, you won’t confuse your success with your greatness or your prosperity with your magnanimity … believe in fact that living is connected to giving.”

IT'S A WONDERFUL LIFE

"You see George, you've really had a wonderful life. Don't you see what a mistake it would be to just throw it away?"

WOODY

"There's a basic rule which runs through all kinds of music, kind of an unwritten rule. I don't know what it is, but I've got it."

MIGGY

"Exuberance is beauty." (William Blake)

Festina Lente

GARAGE SALINGER

JOHN RUSKIN

"Sunshine is delicious, rain is refreshing, wind braces us up, snow is exhilarating; there is really no such thing as bad weather, only different kinds of good weather."

Spitzweg, The Bookworm, 1850

"Literature is the most agreeable way of ignoring life.” Fernando Pessoa

WILLIAM F. BUCKLEY JR.

SYRINX

TINA WEYMOUTH

WALT WHITMAN

"Do I contradict myself? Very well then I contradict myself, (I am large, I contain multitudes)."

H.L. MENCKEN

"Every normal man must be tempted, at times, to spit on his hands, hoist the black flag, and begin slitting throats. But this business, alas, is fatal to the placid moods and fine other-worldliness of the poet."

FYODOR DOSTOEVSKY

"I say let the world go to hell, but I should always have my tea."

DUDLEY

"We all come from our own little planets. That's why we're all different. That's what makes life interesting."

HERMAN MELVILLE

"We're just dancing in the rain ..."

LEO TOLSTOY

"If, then, I were asked for the most important advice I could give, that which I considered to be the most useful to the men of our century, I should simply say: in the name of God, stop a moment, cease your work, look around you."

HAROLD BLOOM

"It is hard to go on living without some hope of encountering the extraordinary."

I'm reading ...

Unlikely General: "Mad" Anthony Wayne and the Battle for America

CURRENT MOON

ARTHUR RIMBAUD

"I have stretched ropes from steeple to steeple; Garlands from window to window; Golden chains from star to star ... And I dance."

RUMI

"When you do things from your soul, you feel a river moving in you, a joy.”

Shunryu Suzuki, "Beginner's Mind"

"In the beginner's mind there are many possibilities, but in the expert's there are few."

JIM HARRISON

van EYCK, PORTRAIT of a MAN in a RED TURBAN, 1433

"The Poet is the Priest of The Invisible." Wallace Stevens

Atget, Notre-Dame de Paris, 1923

Technique.

"Technique is the proof of your seriousness." Wallace Stevens

TIGHT LINES!

W.B. Yeats

THE CAPTAIN

NICHOLAS HAWKSMOOR

THOMAS PAINE

"Whatever is my right as a man is also the right of another; and it becomes my duty to guarantee as well as to possess."

LIBERTY

"...the imprisoned lightning"

WILLIAM F. BUCKLEY JR.

"The best defense against a usurpatory government is an assertive citizenry."

SIR PHILIP PULLMAN

"We don’t need a list of rights and wrongs, tables of dos and don’ts: we need books, time, and silence."

TRUE-BORN

THOMAS MERTON

C.S. LEWIS

THOMAS PAINE

_(14750662474).jpg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(730x380:732x382)/east-wing-demo-2-102025-fab13cffaf33442f8d51ed2281be3197.jpg)