28 February 2018

Joy.

Grimshaw, Roundhay Lake, Leeds, 1893

IN MEMORY of a HAPPY DAY in FEBRUARY

Blessed be Thou for all the joy

My soul has felt today!

O let its memory stay with me

And never pass away!

I was alone, for those I loved

Were far away from me,

The sun shone on the withered grass,

The wind blew fresh and free.

Was it the smile of early spring

That made my bosom glow?

'Twas sweet, but neither sun nor wind

Could raise my spirit so.

Was it some feeling of delight,

All vague and undefined?

No, 'twas a rapture deep and strong,

Expanding in the mind!

Was it a sanguine view of life

And all its transient bliss–

A hope of bright prosperity?

O no, it was not this!

It was a glimpse of truth divine

Unto my spirit given

Illumined by a ray of light

That shone direct from heaven!

I felt there was a God on high

By whom all things were made.

I saw His wisdom and his power

In all his works displayed.

But most throughout the moral world

I saw his glory shine;

I saw His wisdom infinite,

His mercy all divine.

Deep secrets of his providence

In darkness long concealed

Unto the vision of my soul

Were graciously revealed.

But while I wondered and adored

His wisdom so divine,

I did not tremble at his power,

I felt that God was mine.

I knew that my Redeemer lived,

I did not fear to die;

Full sure that I should rise again

To immortality.

I longed to view that bliss divine

Which eye hath never seen,

Like Moses, I would see His face

Without the veil between.

Anne Brontë

Blue.

Blue ice doesn’t always stack up along the Great Lakes shoreline. But when it does form – and its irregular rectangles begin to tower with Michigan’s iconic Mackinac Bridge in the background – it sends photographers running for the perfect shot.

Earliest.

After the Big Bang, it was dark and cold. And then there was light. Now, for the first time, astronomers have glimpsed that dawn of the universe 13.6 billion years ago when the earliest stars were turning on the light in the cosmic darkness.

And if that’s not enough, they may have detected mysterious dark matter at work, too.

The glimpse consisted of a faint radio signal from deep space, picked up by an antenna that is slightly bigger than a refrigerator and costs less than $5 million but in certain ways can go back much farther in time and distance than the celebrated, multibillion-dollar Hubble Space Telescope.

And if that’s not enough, they may have detected mysterious dark matter at work, too.

The glimpse consisted of a faint radio signal from deep space, picked up by an antenna that is slightly bigger than a refrigerator and costs less than $5 million but in certain ways can go back much farther in time and distance than the celebrated, multibillion-dollar Hubble Space Telescope.

Elgar, Variations on an Original Theme, "Enigma," Op.36

Sir Colin Davis leads the London Symphony Orchestra in performing "Nimrod" ...

Schubert, Piano Sonata in B Flat Major, D. 960

Alfred Brendel performs ...

Molto Moderato

Andante Sostenuto

Scherzo and Trio

Allegro -- Presto

Molto Moderato

Andante Sostenuto

Scherzo and Trio

Allegro -- Presto

27 February 2018

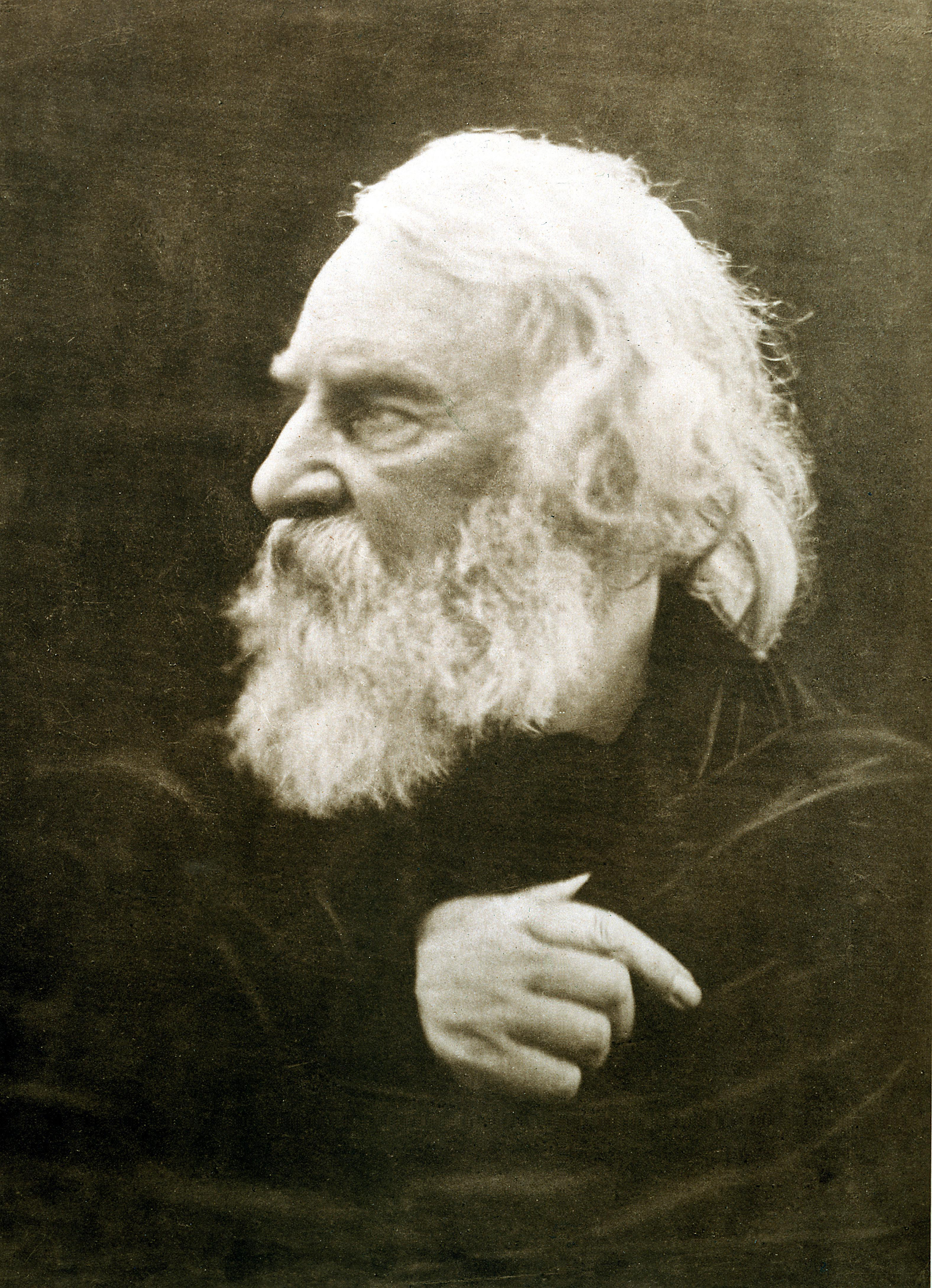

Happy birthday, Longfellow.

Cameron, Longfellow, 1868

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow was born on this day in 1807.

Long at the scene, bewildered and amazed

The writer of this legend then records

The scholar and the world! The endless strife,

But why, you ask me, should this tale be told

As the barometer foretells the storm

What then? Shall we sit idly down and say

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow was born on this day in 1807.

Long at the scene, bewildered and amazed

The trembling clerk in speechless wonder gazed;

Then from the table, by his greed made bold,

He seized a goblet and a knife of gold,

And suddenly from their seats the guests upsprang,

The vaulted ceiling with loud clamors rang,

The archer sped his arrow, at their call,

Shattering the lambent jewel on the wall,

And all was dark around and overhead;--

Stark on the door the luckless clerk lay dead!

The writer of this legend then records

Its ghostly application in these words:

The image is the Adversary old,

Whose beckoning finger points to realms of gold;

Our lusts and passions are the downward stair

That leads the soul from a diviner air;

The archer, Death; the flaming jewel, Life;

Terrestrial goods, the goblet and the knife;

The knights and ladies, all whose flesh and bone

By avarice have been hardened into stone;

The clerk, the scholar whom the love of pelf

Tempts from his books and from his nobler self.

The scholar and the world! The endless strife,

The discord in the harmonies of life!

The love of learning, the sequestered nooks,

And all the sweet serenity of books;

The market-place, the eager love of gain,

Whose aim is vanity, and whose end is pain!

But why, you ask me, should this tale be told

To men grown old, or who are growing old?

It is too late! Ah, nothing is too late

Till the tired heart shall cease to palpitate.

Cato learned Greek at eighty; Sophocles

Wrote his grand Oedipus, and Simonides

Bore off the prize of verse from his compeers,

When each had numbered more than fourscore years,

And Theophrastus, at fourscore and ten,

Had but begun his ?Characters of Men.?

Chaucer, at Woodstock with the nightingales,

At sixty wrote the Canterbury Tales;

Goethe at Weimar, toiling to the last,

Completed Faust when eighty years were past.

These are indeed exceptions; but they show

How far the gulf-stream of our youth may flow

Into the arctic regions of our lives.

Where little else than life itself survives.

As the barometer foretells the storm

While still the skies are clear, the weather warm,

So something in us, as old age draws near,

Betrays the pressure of the atmosphere.

The nimble mercury, ere we are aware,

Descends the elastic ladder of the air;

The telltale blood in artery and vein

Sinks from its higher levels in the brain;

Whatever poet, orator, or sage

May say of it, old age is still old age.

It is the waning, not the crescent moon;

The dusk of evening, not the blaze of noon;

It is not strength, but weakness; not desire,

But its surcease; not the fierce heat of fire,

The burning and consuming element,

But that of ashes and of embers spent,

In which some living sparks we still discern,

Enough to warm, but not enough to burn.

What then? Shall we sit idly down and say

The night hath come; it is no longer day?

The night hath not yet come; we are not quite

Cut off from labor by the failing light;

Something remains for us to do or dare;

Even the oldest tree some fruit may bear;

Not Oedipus Coloneus, or Greek Ode,

Or tales of pilgrims that one morning rode

Out of the gateway of the Tabard Inn,

But other something, would we but begin;

For age is opportunity no less

Than youth itself, though in another dress,

And as the evening twilight fades away

The sky is filled with stars, invisible by day.26 February 2018

Necessary.

Carpenter, From a Dry State, 1915

I will call the world a School instituted for the purpose of teaching little children to read—I will call the human heart the horn Book used in that School—and I will call the Child able to read, the Soul made from that school and its hornbook. Do you not see how necessary a World of Pains and troubles is to school an Intelligence and make it a soul? A Place where the heart must feel and suffer in a thousand diverse ways!

John Keats

Enjoy.

One final paragraph of advice: do not burn yourselves out. Be as I am - a reluctant enthusiast, a part-time crusader, a half-hearted fanatic. Save the other half of yourselves and your lives for pleasure and adventure. It is not enough to fight for the land; it is even more important to enjoy it. While you can. While it’s still here. So get out there and hunt and fish and mess around with your friends, ramble out yonder and explore the forests, climb the mountains, bag the peaks, run the rivers, breathe deep of that yet sweet and lucid air, sit quietly for a while and contemplate the precious stillness, the lovely, mysterious, and awesome space. Enjoy yourselves, keep your brain in your head and your head firmly attached to the body, the body active and alive, and I promise you this much; I promise you this one sweet victory over our enemies, over those desk-bound men and women with their hearts in a safe deposit box, and their eyes hypnotized by desk calculators. I promise you this; You will outlive the bastards.

Edward Abbey

25 February 2018

24 February 2018

23 February 2018

Happy birthday, Pepys.

Kneller, Samuel Pepys, 1689

Samuel Pepys was born on this day in 1633.

Fight the good fight; and always call to mind that it is not you who are mortal, but this body of ours. For your true being is not discerned by perceiving your physical appearance. But what a man's mind is, that is what he is not that individual human shape that we identify through our senses.

Samuel Pepys

Samuel Pepys was born on this day in 1633.

Fight the good fight; and always call to mind that it is not you who are mortal, but this body of ours. For your true being is not discerned by perceiving your physical appearance. But what a man's mind is, that is what he is not that individual human shape that we identify through our senses.

Samuel Pepys

Inquiry.

Reynolds, Self-portrait, 1748

The principal advantage of an academy is, that, besides furnishing able men to direct the student, it will be a repository for the great examples of the art. These are the materials on which genius is to work, and without which the strongest intellect may be fruitlessly or deviously employed. By studying these authentic models, that idea of excellence which is the result of the accumulated experience of past ages may be at once acquired, and the tardy and obstructed progress of our predecessors may teach us a shorter and easier way. The student receives at one glance the principles which many artists have spent their whole lives in ascertaining; and, satisfied with their effect, is spared the painful investigation by which they come to be known and fixed.

This first degree of proficiency is, in painting, what grammar is in literature, a general preparation to whatever species of the art the student may afterwards choose for his more particular application. The power of drawing, modelling, and using colours is very properly called the language of the art; and in this language, the honours you have just received prove you to have made no inconsiderable progress.

When the artist is once enabled to express himself with some degree of correctness, he must then endeavour to collect subjects for expression; to amass a stock of ideas, to be combined and varied as occasion may require. He is now in the second period of study, in which his business is to learn all that has hitherto been known and done. Having hitherto received instructions from a particular master, he is now to consider the art itself as his master. He must extend his capacity to more sublime and general instructions. Those perfections which lie scattered among various masters are now united in one general idea, which is henceforth to regulate his taste and enlarge his imagination. With a variety of models thus before him, he will avoid that narrowness and poverty of conception which attends a bigoted admiration of a single master, and will cease to follow any favourite where he ceases to excel. This period is, however, still a time of subjection and discipline. Though the student will not resign himself blindly to any single authority when he may have the advantage of consulting many, he must still be afraid of trusting his own judgment, and of deviating into any track where he cannot find the footsteps of some former master.

The third and last period emancipates the student from subjection to any authority but what he shall himself judge to be supported by reason. Confiding now in his own judgment, he will consider and separate those different principles to which different modes of beauty owe their original. In the former period he sought only to know and combine excellence, wherever it was to be found, into one idea of perfection; in this he learns, what requires the most attentive survey and the subtle disquisition, to discriminate perfections that are incompatible with each other.

It is indisputably evident that a great part of every man’s life must be employed in collecting materials for the exercise of genius. Invention, strictly speaking, is little more than a new combination of those images which have been previously gathered and deposited in the memory. Nothing can come of nothing. He who has laid up no materials can produce no combinations.

To a young man just arrived in Italy, many of the present painters of that country are ready enough to obtrude their precepts, and to offer their own performances as examples of that perfection which they affect to recommend. The modern, however, who recommends himself as a standard, may justly be suspected as ignorant of the true end, and unacquainted with the proper object of the art which he professes. To follow such a guide will not only retard the student, but mislead him.

On whom, then, can he rely, or who shall show him the path that leads to excellence? The answer is obvious: Those great masters who have traveled the same road with success are the most likely to conduct others. The works of those who have stood the test of ages have a claim to that respect and veneration to which no modern can pretend. The duration and stability of their fame is sufficient to evince that it has not been suspended upon the slender thread of fashion and caprice, but bound to the human heart by every tie of sympathetic approbation. There is no danger of studying too much the works of those great men, but how they may be studied to advantage is an inquiry of great importance.

However the mechanic and ornamental arts may sacrifice to fashion, she must be entirely excluded from the art of painting; the painter must never mistake this capricious changeling for the genuine offspring of nature; he must divest himself of all prejudices in favour of his age or country; he must disregard all local and temporary ornaments, and look only on those general habits that are everywhere and always the same. He addresses his works to the people of every country and every age; he calls upon posterity to be his spectators, and says with Zeuxis, In æternitatem pingo (Paint in Eternity).

This first degree of proficiency is, in painting, what grammar is in literature, a general preparation to whatever species of the art the student may afterwards choose for his more particular application. The power of drawing, modelling, and using colours is very properly called the language of the art; and in this language, the honours you have just received prove you to have made no inconsiderable progress.

When the artist is once enabled to express himself with some degree of correctness, he must then endeavour to collect subjects for expression; to amass a stock of ideas, to be combined and varied as occasion may require. He is now in the second period of study, in which his business is to learn all that has hitherto been known and done. Having hitherto received instructions from a particular master, he is now to consider the art itself as his master. He must extend his capacity to more sublime and general instructions. Those perfections which lie scattered among various masters are now united in one general idea, which is henceforth to regulate his taste and enlarge his imagination. With a variety of models thus before him, he will avoid that narrowness and poverty of conception which attends a bigoted admiration of a single master, and will cease to follow any favourite where he ceases to excel. This period is, however, still a time of subjection and discipline. Though the student will not resign himself blindly to any single authority when he may have the advantage of consulting many, he must still be afraid of trusting his own judgment, and of deviating into any track where he cannot find the footsteps of some former master.

The third and last period emancipates the student from subjection to any authority but what he shall himself judge to be supported by reason. Confiding now in his own judgment, he will consider and separate those different principles to which different modes of beauty owe their original. In the former period he sought only to know and combine excellence, wherever it was to be found, into one idea of perfection; in this he learns, what requires the most attentive survey and the subtle disquisition, to discriminate perfections that are incompatible with each other.

It is indisputably evident that a great part of every man’s life must be employed in collecting materials for the exercise of genius. Invention, strictly speaking, is little more than a new combination of those images which have been previously gathered and deposited in the memory. Nothing can come of nothing. He who has laid up no materials can produce no combinations.

To a young man just arrived in Italy, many of the present painters of that country are ready enough to obtrude their precepts, and to offer their own performances as examples of that perfection which they affect to recommend. The modern, however, who recommends himself as a standard, may justly be suspected as ignorant of the true end, and unacquainted with the proper object of the art which he professes. To follow such a guide will not only retard the student, but mislead him.

On whom, then, can he rely, or who shall show him the path that leads to excellence? The answer is obvious: Those great masters who have traveled the same road with success are the most likely to conduct others. The works of those who have stood the test of ages have a claim to that respect and veneration to which no modern can pretend. The duration and stability of their fame is sufficient to evince that it has not been suspended upon the slender thread of fashion and caprice, but bound to the human heart by every tie of sympathetic approbation. There is no danger of studying too much the works of those great men, but how they may be studied to advantage is an inquiry of great importance.

However the mechanic and ornamental arts may sacrifice to fashion, she must be entirely excluded from the art of painting; the painter must never mistake this capricious changeling for the genuine offspring of nature; he must divest himself of all prejudices in favour of his age or country; he must disregard all local and temporary ornaments, and look only on those general habits that are everywhere and always the same. He addresses his works to the people of every country and every age; he calls upon posterity to be his spectators, and says with Zeuxis, In æternitatem pingo (Paint in Eternity).

Joshua Reynolds

Treasures.

On the following morning, the sun darted his beams from over the hills through the low lattice window. I rose at an early hour, and looked out between the branches of eglantine which overhung the casement. To my surprise Scott was already up and forth, seated on a fragment of stone, and chatting with the workmen employed on the new building. I had supposed, after the time he had wasted upon me yesterday, he would be closely occupied this morning, but he appeared like a man of leisure, who had nothing to do but bask in the sunshine and amuse himself.

I soon dressed myself and joined him. He talked about his proposed plans of Abbotsford; happy would it have been for him could he have contented himself with his delightful little vine-covered cottage, and the simple, yet hearty and hospitable style, in which he lived at the time of my visit. The great pile of Abbotsford, with the huge expense it entailed upon him, of servants, retainers, guests, and baronial style, was a drain upon his purse, a tax upon his exertions, and a weight upon his mind, that finally crushed him.

As yet, however, all was in embryo and perspective, and Scott pleased himself with picturing out his future residence, as he would one of the fanciful creations of his own romances. "It was one of his air castles," he said, "which he was reducing to solid stone and mortar." About the place were strewed various morsels from the ruins of Melrose Abbey, which were to be incorporated in his mansion. He had already constructed out of similar materials a kind of Gothic shrine over a spring, and had surmounted it by a small stone cross.

Among the relics from the Abbey which lay scattered before us, was a most quaint and antique little lion, either of red stone, or painted red, which hit my fancy. I forgot whose cognizance it was; but I shall never forget the delightful observations concerning old Melrose to which it accidentally gave rise. The Abbey was evidently a pile that called up all Scott's poetic and romantic feelings; and one to which he was enthusiastically attached by the most fanciful and delightful of his early associations. He spoke of it, I may say, with affection. "There is no telling," said he, "what treasures are hid in that glorious old pile. It is a famous place for antiquarian plunder; there are such rich bits of old time sculpture for the architect, and old time story for the poet. There is as rare picking in it as a Stilton cheese, and in the same taste—the mouldier the better."

Washington Irving, from "Abbotsford and Newstead Abbey"

22 February 2018

Heart.

Chatham, Approaching Storm, 1991

From a recent Russell Chatham interview done by Cowboys & Indians Magazine ...

C&I: Back to the brush. What do you want people to ultimately take from your paintings, including for the few who can take pride in owning one?

CHATHAM: Excitement. A rush or an energy that comes from something I've put my heart into without false motive or artifice. When art is working, there's a certain joy that's conveyed. Along with a feeling play -- the sense that what the artist was doing when he created this was having a helluva good time. I think people are naturally attracted to that energy, often without really even knowing it, but that's what's making it work for them.

When it comes down to it, that's pretty much what it's always really about, right? Something that's just it.

Happy birthday, Lowell.

Merritt, James Russell Lowell, 1882

James Russell Lowell was born on this day in 1819.

Once to ev'ry man and nation

Comes the moment to decide,

In the strife of truth and falsehood,

For the good or evil side;

Some great cause, some great decision,

Off'ring each the bloom or blight,

And the choice goes by forever

'Twixt that darkness and that light.

Then to side with truth is noble,

When we share her wretched crust,

Ere her cause bring fame and profit,

And 'tis prosperous to be just;

Then it is the brave man chooses

While the coward stands aside.

Till the multitude make virtue

Of the faith they had denied.

By the light of burning martyrs,

Christ, Thy bleeding feet we track,

Toiling up new Calv'ries ever

With the cross that turns not back;

New occasions teach new duties,

Ancient values test our youth;

They must upward still and onward,

Who would keep abreast of truth.

Tho' the cause of evil prosper,

Yet the truth alone is strong;

Tho' her portion be the scaffold,

And upon the throne be wrong;

Yet that scaffold sways the future,

And, behind the dim unknown,

Standeth God within the shadow,

Keeping watch above His own.

Keeping watch above His own.

James Russell Lowell

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

.jpg)