28 June 2018

26 June 2018

Access.

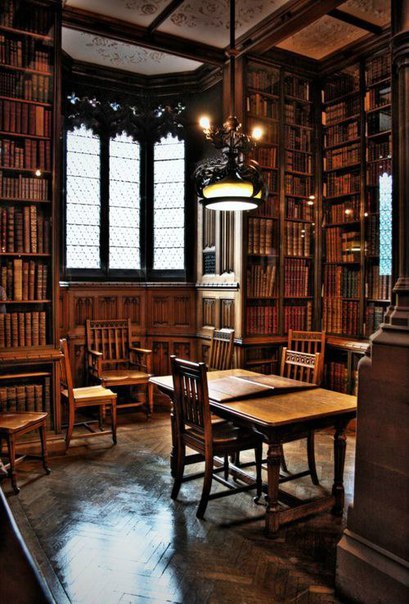

THE HOUSE WAS QUIET and THE WORLD WAS CALM

The house was quiet and the world was calm.

The reader became the book; and summer night

Was like the conscious being of the book.

The house was quiet and the world was calm.

The words were spoken as if there was no book,

Except that the reader leaned above the page,

Wanted to lean, wanted much most to be

The scholar to whom his book is true, to whom

The summer night is like a perfection of thought.

The house was quiet because it had to be.

The quiet was part of the meaning, part of the mind:

The access of perfection to the page.

And the world was calm. The truth in a calm world,

In which there is no other meaning, itself

Is calm, itself is summer and night, itself

Is the reader leaning late and reading there.

Wallace Stevens

Mozart, Violin Concerto No.5 in A Major, K.219

Isaac Stern performs with the Radio France Chamber Orchestra, directed by Alexander Schneider ...

Humbly.

Chatham, Fog on Mt. Tamalpais, n/d

Living in the forest, I feel the presence of many "treasures" breathing quietly in nature. I call this presence "Shizuka." "Shizuka" means cleansed, pure, clear, and untainted. I walk around the forest and harvest my "Shizuka" treasures from soil. I try to catch the faint light radiated by these treasures with both my eyes and my camera.

In Tao Te Ching , an ancient Chinese philosopher Lao-tzu wrote, "A great presence is hard to see. A great sound is hard to hear. A great figure has no form." What he means is that the world is full of noises that we humans are not capable of hearing. For example, we cannot hear the noises created by the movement of the universe. Although these sounds exist, we ignore them altogether and act as if only what we can hear exists. Lao-tzu teaches us to humbly accept that we only play a small part in the grand scheme of the universe.

Masao Yamamoto

Masao Yamamoto

25 June 2018

24 June 2018

Together.

Wyeth, Spruce Grove, 1970

OFF the TRAIL

for Carole

Gary Snyder

OFF the TRAIL

for Carole

We are free to find our own way

Over rocks – through the trees –

Where there are no trails. The ridge and the forest

Present themselves to our eyes and feet

Which decide for themselves

In their old learned wisdom of doing

Where the wild will take us. We have

Been here before. It’s more intimate somehow

Than walking the paths that lay out some route

That you stick to,

All paths are possible, many will work,

Being blocked is its own kind of pleasure,

Getting through is a joy, the side-trips

And detours show down logs and flowers,

The deer paths straight up, the squirrel tracks

Across, the outcroppings lead us on over.

Resting on treetrunks,

Stepping out on the bedrock, angling and eyeing

Both making choices – now parting our ways –

And later rejoin; I’m right, you’re right,

We come out together. Mattake, “Pine Mushroom,”

Heaves at the base of a stump. The dense matted floor

Of Red Fir needles and twigs. This is wild!

We laugh, wild for sure,

Because no place is more than another,

All places total,

And our ankles, knees, shoulders &

Haunches know right where they are.

Recall how the Dao De

Jing puts it: the trail’s not the way.

No path will get you there, we’re off the trail,

You and I, and we chose it! Our trips out of doors

Through the years have been practice

For this ramble together,

Deep in the mountains

Side by side,

Over the rocks, through the trees.

Gary Snyder

Beethoven, String Quartet No. 1 in F major, Op. 18

The Alban Berg String Quartet performs ...

Allegro con brio

Adagio affettuoso ed appassionato

Scherzo: Allegro molto

Allegro

Allegro con brio

Adagio affettuoso ed appassionato

Scherzo: Allegro molto

Allegro

23 June 2018

Logic.

The characteristically greasy, meandering, poetic narrative churns between the writer’s mind and esophagus and stomach, turning around a somewhat dumb question: “Is there an interior logic to overeating?”

To that end, Harrison had, in just over 24 hours, consumed all manner of organs from a small zoo of fauna—poultry and crayfish soup; tartines of foie gras, truffles, and lard; another soup of cucumbers and squab, served with conch fritters; a crayfish bisque; oysters on toast; jellied poultry loaf; Baltic herring; tart of calf’s brains; sea urchin omelet; fillet of sole; monkfish livers; pike and parsley; oven-glazed brill served with fresh cream, anchovies, and roasted currents; another stew of suckling pig, slow-cooked in a red-wine sauce thickened with its own blood, onions, and bacon; a warm terrine of hare with preserved plums; a poached eel with chicken wing tips and testicles in a pool of tarragon butter; glazed partridge breasts; a savory of eggs poached in Chimay ale; and then a mille-feuille of puff pastry sandwiches with sardines and leeks; bites of stuffed ravioli; more poached eggs; squab hearts; a “light” stew of veal breast in a puree of ham and oysters; gratin of beef cheeks; more squab (“spit-roasted”); wild duck with black olives and orange zest, a buisson (bush) of more crayfish with little slabs of grilled goose liver; a terrine of the tips of calves’ ears; hare cooked in port wine inside a calf’s bladder—plus crispy breaded asparagus, a sponge cake with fruit preserves, cucumbers stewed in wine, another few rounds of salads, cream of grilled pistachios, meringues, macaroons, and chocolate cigarettes. The night concluded with an entire additional dessert course in the restaurant’s nearby salon, followed by 80-year-old brandy and some Havana Churchills.

Time.

The people in my class, including me, do not need to be taught. We need simply to be encouraged, to be given heart, to be allowed to grow into our own large hearts. We do not need to be governed by external schedules—by the ticking of the ubiquitous classroom clock—nor told what and when we need to learn, nor what we need to express, but instead we need to be given time, not as a constraint, but as a gift in a supportive place where we can explore what we want and who we are, with the assistance of others who care about us also.

Derrick Jensen

Derrick Jensen

22 June 2018

Noticing.

The GRASS

The grass has so little to do,—

A spear of simple green,

With only butterflies to brood,

And bees to entertain,

And stir all day to pretty tunes

The breezes fetch along.

And hold the sunshine in its lap.

And bow to everything;

And thread the dews all night, like pearls,

And make itself so fine,—

A duchess were too common

For such a noticing.

For such a noticing.

Emily Dickinson

21 June 2018

Leap.

Philip Pullman

XTC, "Summer's Cauldron"

Drowning here in summer's cauldron

Under mats of flower lava

Please don't pull me out this is how I would want to go

Breathing in the boiling butter

Fruit of sweating golden Inca

Please don't heed my shout

I'll relax in the undertow

When Miss Moon lays down

And Sir Sun stands up

Me I'm found floating round and round

Like a bug in brandy

In this big bronze cup

Drowning here in summer's cauldron

Trees are dancing drunk with nectar

Grass is waving underwater

Please don't pull me out this is how I would want to go

Insect bomber Buddhist droning

Copper chord of August's organ

Please don't heed my shout

I'll relax in the undertow

When Miss Moon lays down

In her hilltop bed

And Sir Sun stands up

Raise his regal head

Me I'm found floating round and round

Like a bug in brandy

In this big bronze cup

Drowning here in summer's cauldron

Summer.

The introduction to Dandelion Wine, by Ray Bradbury

JUST THIS SIDE OF BYZANTIUM: an introduction

This book, like most of my books and stories, was a surprise. I began to learn the nature of such surprises, thank God, when I was fairly young as a writer. Before that, like every beginner, I thought you could beat, pummel, and thrash an idea into existence. Under such treatment, of course, any decent idea folds up its paws, turns on its back, fixes its eyes on eternity, and dies.

It was with great relief, then, that in my early twenties I floundered into a word-association process in which I simply got out of bed each morning, walked to my desk, and put down any word or series of words that happened along in my head.

I would then take arms against the word, or for it, and bring on an assortment of characters to weigh the word and show me its meaning in my own life. An hour or two hours later, to my amazement, a new story would be finished and done. The surprise was total and lovely. I soon found that I would have to work this way for the rest of my life.

First I rummaged my mind for words that could describe my personal nightmares, fears of night and time from my childhood, and shaped stories from these.

Then I took a long look at the green apple trees and the old house I was born in and the house next door where lived my grandparents, and all the lawns of the summers I grew up in, and I began to try words for all that.

What you have here in this book then is a gathering of dandelions from all those years. The wine metaphor which appears again and again in these pages is wonderfully apt. I was gathering images all of my life, storing them away, and forgetting them. Somehow I had to send myself back, with words as catalysts, to open the memories out and see what they had to offer.

So from the age of twenty-four to thirty-six hardly a day passed when I didn’t stroll myself across a recollection of my grandparents’ northern Illinois grass, hoping to come across some old half-burnt firecracker, a rusted toy, or a fragment of letter written to myself in some young year hoping to contact the older person I became to remind him of his past, his life, his people, his joys, and his drenching sorrows.

It became a game that I took to with immense gusto: to see how much I could remember about dandelions themselves, or picking wild grapes with my father and brother, rediscovering the mosquito-breeding ground rain barrel by the side bay window, or searching out the smell of the gold-fuzzed bees that hung around our back porch grape arbor. Bees do have a smell, you know, and if they don’t they should, for their feet are dusted with spices from a million flowers.

An then I wanted to call back what the ravine was like, especially on those nights when walking home late across town, after seeing Lon Chaney’s delicious fright The Phantom of the Opera, my brother Skip would run ahead and hide under the ravine-creek bridge like the Lonely One and leap out and grab me, shrieking, so I ran, fell, and ran again, gibbering all the way home. That was great stuff.

Along the way I came upon and collided, through word-association, with old and true friendships. I borrowed my friend John Huff from my childhood in Arizona and shipped him East to Green Town so that I could say good-bye to him properly.

Along the way I sat me down to breakfasts, lunches, and dinners with the long dead and much loved. For I was a boy who did indeed love his parents and grandparents and his brother, even when that brother “ditched” him.

Along the way, I found myself in the basement working the wine-press for my father, or on the front porch Independence night helping my Uncle Bion load and fire his home-made brass cannon.

Thus I fell into surprise. No one told me to surprise myself, I might add. I came on the old and best ways of writing through ignorance and experiment and was startled when truths leaped out of bushes like quail before gunshot. I blunwas somehow true.

So I turned myself into a boy running to bring a dipper of clear rainwater out of that barrel by the side of the house. And, of course, the more water you dip out the more flows in. The flow has never ceased. Once I learned to keep going back

and back again to those times, I had plenty of memories and sense impressions to play with, not work with, no, play with. Dandelion Wine is nothing if it is not the boy-hid-in-the-man playing in the fields of the Lord on the green grass of other Augusts in the midst of starting to grow up, grow old, and sense darkness waiting under the trees to seed the blood.

I was amused and somewhat astonished at a critic a few years back who wrote an article analyzing Dandelion Wine plus the more realistic work of Sinclair Lewis, wondering how I could have been born and raised in Waukegan, which I renamed Green Town for my novel, and not noticed how ugly the harbor was and how depressing the coal docks and railyards down below the town.

But, of course, I had noticed them and, genetic enchanter that I was, was fascinated by their beauty. Trains and boxcars and the smell of coal and fire are not ugly to children. Ugliness is a concept that we happen on later and become self-conscious about. Counting boxcars is a prime activity of boys. Their elders fret and fume and jeer at the train that holds them up, but boys happily count and cry the names of the cars as they pass from far places.

And again, that supposedly ugly railyard was where carnivals and circuses arrived with elephants who washed the brick pavements with mighty streaming acid waters at five in the dark morning.

As for the coal from the docks, I went down in my basement every autumn to await the arrival of the truck and its metal chute, which clanged down and released a ton of beauteous meteors that fell out of far space into my cellar and threatened to bury me beneath dark treasures.

In other words, if your boy is a poet, horse manure can only mean flowers to him; which is, of course, what horse manure has always been about.

Perhaps a new poem of mine will explain more than this introduction about the germination of all the summers of my life into one book.

Here’s the start of the poem:

Byzantium, I come not from,

But from another time and place

Whose race was simple, tried and true;

As boy

I dropped me forth in Illinois.

A name with neither love nor grace

Was Waukegan, there I came from

And not, good friends, Byzantium.

The poem continues, describing my lifelong relationship to my birthplace:

And yet in looking back I see

From topmost part of farthest tree

A land as bright, beloved and blue

As any Yeats found to be true.

Waukegan, visited by me often since, is neither homelier nor more beautiful than any other small Midwestern town. Much of it is green. The trees do touch in the middle of streets. The street in front of my old home is still paved with red bricks. In what way then was the town special? Why, I was born there. It was my life. I had to write of it as I saw fit:

So we grew up with mythic dead

To spoon upon midwestern bread

And spread old gods’ bright marmalade

To slake in peanut-butter shade,

Pretending there beneath our sky

That it was Aphrodite’s thigh…

While by the porch-rail calm and bold

His words pure wisdom, stare pure gold

My grandfather, a myth indeed,

Did all of Plato supercede

While Grandmama in rockingchair

Sewed up the raveled sleeve of care

Crocheted cool snowflakes rare and bright

To winter us on summer night.

And uncles, gathered with their smokes

Emitted wisdoms masked as jokes,

And aunts as wise as Delphic maids

Dispensed prophetic lemonades

To boys knelt there as acolytes

To Grecian porch on summer nights;

Then went to bed, there to repent

The evils of the innocent;

The gnat-sins sizzling in their ears

Said, through the nights and through the years

Not Illinois nor Waukegan

But blither sky and blither sun.

Though mediocre all our Fates

And Mayor not as bright as Yeats

Yet still we knew ourselves. The sum?

Byzantium.

Byzantuim.

Waukegan/ Green Town/ Byzantium.

Green Town did exist, then?

Yes, and again, yes.

Was there a real boy named John Huff? There was. And that was truly his name. But he didn’t go away from me, I went away from him. But, happy ending, he is still alive, forty-two years later, and remembers our love.

Was there a Lonely One? There was, and that was his name. And he moved around at night in my home town when I was six years old and he frightened everyone and was never captured.

Most importantly, did the big house itself, with Grandpa and Grandma and the boarders and uncles and aunts in it exist? I have answered that.

Is the ravine real and deep and dark at night? It was, it is. I took my daughters there a few years back, fearful that the ravine might have gone shallow with time. I am relieved and happy to report that the ravine is deeper, darker, and more mysterious than ever. I would not, even now, go home through there after seeing The Phantom of the Opera.

So there you have it. Waukegan was Green Town was Byzantium, with all the happiness that that means, with all the sadness that these names imply. The people there were gods and midgets and knew themselves mortal and so the midgets walked tall so as not to embarrass the gods and the gods crouched so as to make the small ones feel at home. And, after all, isn’t that what life is all about, the ability to go around back and come up inside other people’s heads to look out at the damned fool miracle and say: oh, so that’s how you see it!? Well, now, I must remember that.

Here is my celebration, then, of death as well as life, dark as well as light, old as well as young, smart and dumb combined, sheer joy as well as complete terror written by a boy who once hung upside down in trees, dressed in his bat costume with candy fangs in his mouth, who finally fell out of the trees when he was twelve and went and found a toy-dial typewriter and wrote his first “novel.”

A final memory.

Fire balloons.

You rarely see them these days, though in some countries, I hear, they are still filled with warm breath from a small straw fire hung beneath.

But in 1925 Illinois, we still had them, and one of the last memories I have of my grandfather is the last hour of a Fourth of July night forty-eight years ago when Grandpa and I walked out on the lawn and lit a small fire and filled the pear-shaped red-white-and-blue-striped paper balloon with hot air, and held the flickering bright-angel presence in our hands a final moment in front of a porch lined with uncles and aunts and cousins and mothers and fathers, and then, very softly, let the

thing that was life and light and mystery go out of our fingers up on the summer night air and away over the beginning-to-sleep houses, among the stars, as fragile, as wondrous, as vulnerable, as lovely as life itself.

I see my grandfather there looking up at that strange drifting light, thinking his own still thoughts. I see me, my eyes filled with tears, because it was all over, the night was done, I knew there would never be another night like this.

No one said anything. We all just looked up at the sky and we breathed out and in and we all thought the same things, but nobody said. Someone finally had to say, though, didn’t they? And that one is me.

The wine still waits in the cellars below.

My beloved family still sits on the porch in the dark.

The fire balloon still drifts and burns in the night sky of an as yet unburied summer.

Why and how?

Because I say it is so.

Ray Bradbury

Summer, 1974

Your hymnal is here.

Fire balloons aloft in Thailand.

Basic fire balloon how-to is here.

20 June 2018

Mahler, Symphony No. 5

Leonard Bernstein conducts the Vienna Philharmonic performing the Adagietto ...

Singing.

Gabriel Rosenstock, from Haiku: The Gentle Art of Disappearing

19 June 2018

John Prine, "God Only Knows"

God only knows the price that you pay

For the ones you hurt along the way

If I should betray myself today

Then God only knows the price I pay

Then God only knows the price I pay

Committed.

Until one is committed, there is hesitancy, the chance to draw back, always ineffectiveness. Concerning all acts of initiative and creation, there is one elementary truth, the ignorance of which kills countless ideas and splendid plans: that the moment one definitely commits oneself, then providence moves too. All sorts of things occur to help one that would never otherwise have occurred. A whole stream of events issues from the decision, raising in one's favor all manner of unforeseen incidents, meetings and material assistance which no person could have dreamed would have come his or her way. Whatever you can do or dream you can, begin it. Boldness has genius, power and magic in it. Begin it now.

Johann Wolgang von Goethe

18 June 2018

Dark.

Chatham, Fishing the Colorado, 2000

In the midnight Arctic seas,

stained tropical rivers at dawn,

the Gulf Stream at noon,

where thin shafts of light

chisel down into the blue-black;

a small creek in evening shade

beneath willows and sycamores;

in northern rivers

where salmon lie

in deep viridian hallows.

It is always the dark water

which promises the most.

Russell Chatham

In the midnight Arctic seas,

stained tropical rivers at dawn,

the Gulf Stream at noon,

where thin shafts of light

chisel down into the blue-black;

a small creek in evening shade

beneath willows and sycamores;

in northern rivers

where salmon lie

in deep viridian hallows.

It is always the dark water

which promises the most.

Russell Chatham

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-1297719-1375058611-7247.jpeg.jpg)

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-472264-1370407935-9119.jpeg.jpg)

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg/497px-Thomas_Sully_-_The_Student_(Rosalie_Kemble_Sully)_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)