It's only the giving that makes you what you are.

31 December 2023

Divine.

Surely everyone is aware of the divine pleasures which attend a wintry fireside; candles at four o'clock, warm hearthrugs, tea, a fair tea-maker, shutters closed, curtains flowing in ample draperies to the floor, whilst the wind and rain are raging audibly without.

Thomas De Quincey

Sphering.

Next I'll cause my hopeful lad,

If a wild apple can be had,

To crown the hearth;

Lar thus conspiring with our mirth;

Then to infuse

Our browner ale into the cruse;

Which, sweetly spiced, we'll first carouse

Unto the Genius of the house.

Then the next health to friends of mine.

Loving the brave Burgundian wine,

High sons of pith,

Whose fortunes I have frolick'd with;

Such as could well

Bear up the magic bough and spell;

And dancing 'bout the mystic Thyrse,

Give up the just applause to verse;

To those, and then again to thee,

We'll drink, my Wickes, until we be

Plump as the cherry,

Though not so fresh, yet full as merry

As the cricket,

The untamed heifer, or the pricket,1

Until our tongues shall tell our ears,

We're younger by a score of years.

Thus, till we see the fire less shine

From th' embers than the kitling's eyne,

We'll still sit up,

Sphering about the wassail cup,

To all those times

Which gave me honour for my rhymes;

The coal once spent, we'll then to bed,

Far more than night bewearied.

Robert Herrick

Lore.

Greg Brownderville in discussion with Ronald Hutton ...

"The Mystery of Folklore"

"Living the Lore"

Leadership.

If you want to build a ship, don’t drum up the men to gather wood, divide the work, and give orders. Instead, teach them to yearn for the vast and endless sea.

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

Leadership.

Coach Campbell reacts to Lions penalty on 2-point conversion vs. Cowboys ...

Sprung.

Friedrich, Winter Landscape, 1811

Sweet music, sweeter far

Than any song is sweet:

Sweet music, heavenly rare,

Mine ears, O peers, doth greet.

You gentle flocks, whose fleeces, pearled with dew,

Resemble heaven, whom golden drops make bright,

Listen, O listen, now, O not to you

Our pipes make sport to shorten weary night;

But voices most divine

Make blissful harmony:

Voices that seem to shine,

For what else clears the sky?

Tunes can we hear, but not the singers see,

The tunes divine, and so the singers be.

Lo, how the firmament

Within an azure fold

The flock of stars hath pent,

That we might them behold;

Yet from their beams proceedeth not this light,

Nor can their crystals such reflection give.

What then doth make the element so bright?

The heavens are come down upon earth to live.

But hearken to the song,

Glory to glory's king,

And peace all men among,

These quiristers do sing.

Angels they are, as also (Shepherds) he

Whom in our fear we do admire to see.

Let not amazement blind

Your souls, said he, annoy:

To you and all mankind

My message bringeth joy.

For lo, the world's great Shepherd now is born

A blessed babe, an infant full of power:

After long night uprisen is the morn,

Renowning Bethl'em in the Saviour.

Sprung is the perfect day,

By prophets seen afar:

Sprung is the mirthful May,

Which winter cannot mar.

In David's city doth this sun appear

Clouded in flesh, yet, shepherds, sit we here?

Edward Bolton

Red-Letter.

Chapter 1: First Quarter

Here are not many people - and as it is desirable that a story-teller and a story-reader should establish a mutual understanding as soon as possible, I beg it to be noticed that I confine this observation neither to young people nor to little people, but extend it to all conditions of people: little and big, young and old: yet growing up, or already growing down again - there are not, I say, many people who would care to sleep in a church. I don’t mean at sermon-time in warm weather (when the thing has actually been done, once or twice), but in the night, and alone. A great multitude of persons will be violently astonished, I know, by this position, in the broad bold Day. But it applies to Night. It must be argued by night, and I will undertake to maintain it successfully on any gusty winter’s night appointed for the purpose, with any one opponent chosen from the rest, who will meet me singly in an old churchyard, before an old church-door; and will previously empower me to lock him in, if needful to his satisfaction, until morning.

For the night-wind has a dismal trick of wandering round and round a building of that sort, and moaning as it goes; and of trying, with its unseen hand, the windows and the doors; and seeking out some crevices by which to enter. And when it has got in; as one not finding what it seeks, whatever that may be, it wails and howls to issue forth again: and not content with stalking through the aisles, and gliding round and round the pillars, and tempting the deep organ, soars up to the roof, and strives to rend the rafters: then flings itself despairingly upon the stones below, and passes, muttering, into the vaults. Anon, it comes up stealthily, and creeps along the walls, seeming to read, in whispers, the Inscriptions sacred to the Dead. At some of these, it breaks out shrilly, as with laughter; and at others, moans and cries as if it were lamenting. It has a ghostly sound too, lingering within the altar; where it seems to chaunt, in its wild way, of Wrong and Murder done, and false Gods worshipped, in defiance of the Tables of the Law, which look so fair and smooth, but are so flawed and broken. Ugh! Heaven preserve us, sitting snugly round the fire! It has an awful voice, that wind at Midnight, singing in a church!

But, high up in the steeple! There the foul blast roars and whistles! High up in the steeple, where it is free to come and go through many an airy arch and loophole, and to twist and twine itself about the giddy stair, and twirl the groaning weathercock, and make the very tower shake and shiver! High up in the steeple, where the belfry is, and iron rails are ragged with rust, and sheets of lead and copper, shrivelled by the changing weather, crackle and heave beneath the unaccustomed tread; and birds stuff shabby nests into corners of old oaken joists and beams; and dust grows old and grey; and speckled spiders, indolent and fat with long security, swing idly to and fro in the vibration of the bells, and never loose their hold upon their thread-spun castles in the air, or climb up sailor-like in quick alarm, or drop upon the ground and ply a score of nimble legs to save one life! High up in the steeple of an old church, far above the light and murmur of the town and far below the flying clouds that shadow it, is the wild and dreary place at night: and high up in the steeple of an old church, dwelt the Chimes I tell of.

They were old Chimes, trust me. Centuries ago, these Bells had been baptized by bishops: so many centuries ago, that the register of their baptism was lost long, long before the memory of man, and no one knew their names. They had had their Godfathers and Godmothers, these Bells (for my own part, by the way, I would rather incur the responsibility of being Godfather to a Bell than a Boy), and had their silver mugs no doubt, besides. But Time had mowed down their sponsors, and Henry the Eighth had melted down their mugs; and they now hung, nameless and mugless, in the church-tower.

Not speechless, though. Far from it. They had clear, loud, lusty, sounding voices, had these Bells; and far and wide they might be heard upon the wind. Much too sturdy Chimes were they, to be dependent on the pleasure of the wind, moreover; for, fighting gallantly against it when it took an adverse whim, they would pour their cheerful notes into a listening ear right royally; and bent on being heard on stormy nights, by some poor mother watching a sick child, or some lone wife whose husband was at sea, they had been sometimes known to beat a blustering Nor’ Wester; aye, ‘all to fits,’ as Toby Veck said; - for though they chose to call him Trotty Veck, his name was Toby, and nobody could make it anything else either (except Tobias) without a special act of parliament; he having been as lawfully christened in his day as the Bells had been in theirs, though with not quite so much of solemnity or public rejoicing.

For my part, I confess myself of Toby Veck’s belief, for I am sure he had opportunities enough of forming a correct one. And whatever Toby Veck said, I say. And I take my stand by Toby Veck, although he did stand all day long (and weary work it was) just outside the church-door. In fact he was a ticket-porter, Toby Veck, and waited there for jobs.

And a breezy, goose-skinned, blue-nosed, red-eyed, stony-toed, tooth-chattering place it was, to wait in, in the winter-time, as Toby Veck well knew. The wind came tearing round the corner - especially the east wind - as if it had sallied forth, express, from the confines of the earth, to have a blow at Toby. And oftentimes it seemed to come upon him sooner than it had expected, for bouncing round the corner, and passing Toby, it would suddenly wheel round again, as if it cried ‘Why, here he is!’ Incontinently his little white apron would be caught up over his head like a naughty boy’s garments, and his feeble little cane would be seen to wrestle and struggle unavailingly in his hand, and his legs would undergo tremendous agitation, and Toby himself all aslant, and facing now in this direction, now in that, would be so banged and buffeted, and to touzled, and worried, and hustled, and lifted off his feet, as to render it a state of things but one degree removed from a positive miracle, that he wasn’t carried up bodily into the air as a colony of frogs or snails or other very portable creatures sometimes are, and rained down again, to the great astonishment of the natives, on some strange corner of the world where ticket-porters are unknown.

But, windy weather, in spite of its using him so roughly, was, after all, a sort of holiday for Toby. That’s the fact. He didn’t seem to wait so long for a sixpence in the wind, as at other times; the having to fight with that boisterous element took off his attention, and quite freshened him up, when he was getting hungry and low-spirited. A hard frost too, or a fall of snow, was an Event; and it seemed to do him good, somehow or other - it would have been hard to say in what respect though, Toby! So wind and frost and snow, and perhaps a good stiff storm of hail, were Toby Veck’s red-letter days ...

Grace.

Rembrandt, Self-Portrait, 1629

There is a twilight zone in our hearts that we ourselves cannot see. Even when we know quite a lot about ourselves -- our gifts and weaknesses, our ambitions and aspirations, our motives and our drives -- large parts of ourselves remain in the shadow of consciousness. This is a very good thing. We will always remain partially hidden to ourselves. Other people, especially those who love us, can often see our twilight zones better than we ourselves can. The way we are seen and understood by others is different from the way we see and understand ourselves. We will never fully know the significance of our presence in the lives of our friends. That's a grace, a grace that calls us not only to humility, but to a deep trust in those who love us. It is the twilight zones of our hearts where true friendships are born.

Henri Nouwen, from Bread for the Journey

Now.

Unknown, Sunset Through the Trees, n/d

Ye who have scorned each other,

Or injured friend or brother,

In this fast-fading year;

Ye who, by word or deed,

Have made a kind heart bleed,

Come gather here!

Let sinned against and sinning

Forget their strife's beginning,

And join in friendship now.

Be links no longer broken,

Be sweet forgiveness spoken

Under the Holly-Bough.

Ye who have loved each other,

Sister and friend and brother,

In this fast-fading year:

Mother and sire and child,

Young man and maiden mild,

Come gather here;

And let your heart grow fonder,

As memory shall ponder

Each past unbroken vow;

Old loves and younger wooing

Are sweet in the renewing

Under the Holly-Bough.

Ye who have nourished sadness,

Estranged from hope and gladness

In this fast-fading year;

Ye with o'erburdened mind,

Made aliens from your kind,

Come gather here.

Let not the useless sorrow

Pursue you night and morrow,

If e'er you hoped, hope now.

Take heart,— uncloud your faces,

And join in our embraces

Under the Holly-Bough.

Charles MacKay

Thanks for the image, Kurt.

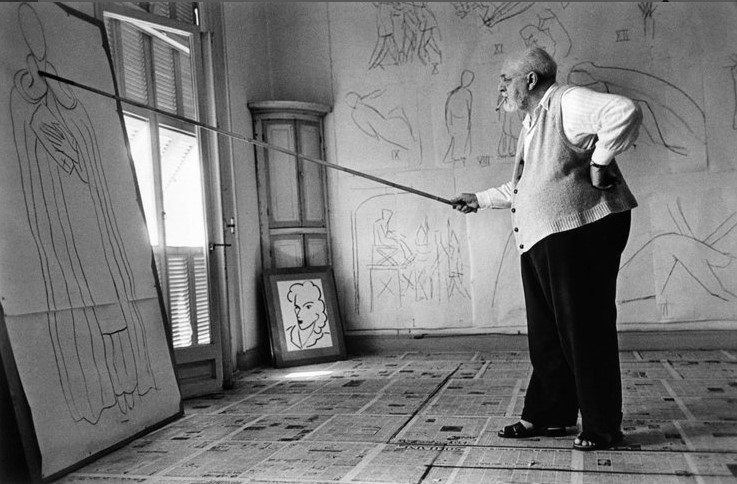

Happy Birthday, Matisse

What I dream of is an art of balance, of purity and serenity devoid of troubling or depressing subject matter, a soothing, calming influence on the mind, rather like a good armchair which provides relaxation from physical fatigue.

Henri Matisse, born on this day in 1869

28 December 2023

26 December 2023

Prod.

I know, you never intended to be in this world.

But you’re in it all the same.

So why not get started immediately.

I mean, belonging to it.

There is so much to admire, to weep over.

And to write music or poems about.

Bless the feet that take you to and fro.

Bless the eyes and the listening ears.

Bless the tongue, the marvel of taste.

Bless touching.

You could live a hundred years, it’s happened.

Or not.

I am speaking from the fortunate platform

of many years,

none of which, I think, I ever wasted.

Do you need a prod?

Do you need a little darkness to get you going?

Let me be as urgent as a knife, then,

and remind you of Keats,

so single of purpose and thinking, for a while,

he had a lifetime.

Mary Oliver

Wonder.

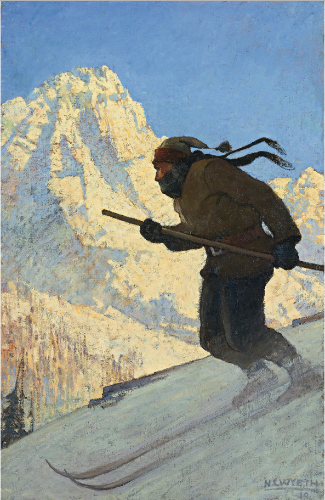

Wyeth, N.C., The Skier, 1911

Shakespeare wrote: "There is nothing more confining than the prison we don’t know we are in." In other words, whatever we are not conscious of can have a deep hold on us. In critical moments, we can wind up doing its bidding while believing we are making our own choices in life. We are in just such a prison of our own making when we act as if the common world of fact and figures is not only the "real world," but also the only world.

The prison of the modern mind is partly created by the common belief that "reality" can be limited to logic, statistics, and provable facts. Not that the literal world is "unreal," rather that it is the first level of reality and can never depict all that is truly Real. Restricting all modes of presence to a single plane of being leads to being trapped in a narrow view of life and imprisoned in the linear trap of time. Too much "hard reality" and the world becomes as if flat again; we lose touch with all that makes this earth a place of wonder and beauty and hidden possibilities.

Michael Meade

Neale, "Good King Wenceslas"

The Danish National Vocal Ensemble does the honors, conducted by Michael Bojesen, with Michala Petri ...

25 December 2023

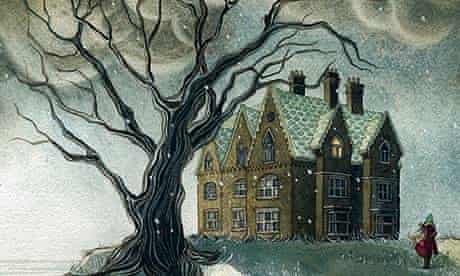

Haunted.

On our way homeward his heart seemed overflowing with generous and happy feelings. As we passed over a rising ground which commanded something of a prospect, the sounds of rustic merriment now and then reached our ears; the Squire paused for a few moments, and looked around with an air of inexpressible benignity. The beauty of the day was of itself sufficient to inspire philanthropy.Notwithstanding the frostiness of the morning, the sun in his cloudless journey had acquired sufficient power to melt away the thin covering of snow from every southern declivity, and to bring out the living green which adorns an English landscape even in mid-winter. Large tracts of smiling verdure contrasted with the dazzling whiteness of the shaded slopes and hollows. Every sheltered bank, on which the broad rays rested, yielded its silver rill of cold and limpid water, glittering through the dripping grass; and sent up slight exhalations to contribute to the thin haze that hung just above the surface of the earth. There was something truly cheering in this triumph of warmth and verdure over the frosty thraldom of winter; it was, as the Squire observed, an emblem of Christmas hospitality, breaking through the chills of ceremony and selfishness, and thawing every heart into a flow. He pointed with pleasure to the indications of good cheer reeking from the chimneys of the comfortable farm-houses and low thatched cottages. "I love," said he, "to see this day well kept by rich and poor; it is a great thing to have one day in the year, at least, when you are sure of being welcome wherever you go, and of having, as it were, the world all thrown open to you; and I am almost disposed to join with Poor Robin, in his malediction of every churlish enemy to this honest festival:—"Those who at Christmas do repine,And would fain hence despatch him,May they with old Duke Humphry dine,Or else may Squire Ketch catch 'em."The Squire went on to lament the deplorable decay of the games and amusements which were once prevalent at this season among the lower orders, and countenanced by the higher: when the old halls of castles and manor-houses were thrown open at daylight; when the tables were covered with brawn, and beef, and humming ale; when the harp and the carol resounded all day long, and when rich and poor were alike welcome to enter and make merry. "Our old games and local customs," said he, "had a great effect in making the peasant fond of his home, and the promotion of them by the gentry made him fond of his lord. They made the times merrier, and kinder, and better; and I can truly say, with one of our old poets,—"I like them well—the curious precisenessAnd all-pretended gravity of thoseThat seek to banish hence these harmless sports,Have thrust away much ancient honesty."The nation," continued he, "is altered; we have almost lost our simple true-hearted peasantry. They have broken asunder from the higher classes, and seem to think their interests are separate. They have become too knowing, and begin to read newspapers, listen to alehouse politicians, and talk of reform. I think one mode to keep them in good humour in these hard times would be for the nobility and gentry to pass more time on their estates, mingle more among the country people, and set the merry old English games going again."Such was the good Squire's project for mitigating public discontent; and, indeed, he had once attempted to put his doctrine in practice, and a few years before had kept open house during the holidays in the old style. The country people, however, did not understand how to play their parts in the scene of hospitality; many uncouth circumstances occurred; the manor was overrun by all the vagrants of the country, and more beggars drawn into the neighbourhood in one week than the parish officers could get rid of in a year. Since then he had contented himself with inviting the decent part of the neighbouring peasantry to call at the hall on Christmas day, and distributing beef, and bread, and ale, among the poor, that they might make merry in their own dwellings.

The dinner was served up in the great hall, where the Squire always held his Christmas banquet. A blazing crackling fire of logs had been heaped on to warm the spacious apartment, and the flame went sparkling and wreathing up the wide-mouthed chimney. The great picture of the crusader and his white horse had been profusely decorated with greens for the occasion; and holly and ivy had likewise been wreathed round the helmet and weapons on the opposite wall, which I understood were the arms of the same warrior. I must own, by the by, I had strong doubts about the authenticity of the painting and armour as having belonged to the crusader, they certainly having the stamp of more recent days; but I was told that the painting had been so considered time out of mind; and that as to the armour, it had been found in a lumber room, and elevated to its present situation by the Squire, who at once determined it to be the armour of the family hero; and as he was absolute authority on all such subjects in his own household, the matter had passed into current acceptation. A sideboard was set out just under this chivalric trophy, on which was a display of plate that might have vied (at least in variety) with Belshazzar's parade of the vessels of the temple; "flagons, cans, cups, beakers, goblets, basins, and ewers;" the gorgeous utensils of good companionship, that had gradually accumulated through many generations of jovial housekeepers. Before these stood the two Yule candles beaming like two stars of the first magnitude; other lights were distributed in branches, and the whole array glittered like a firmament of silver.We were ushered into this banqueting scene with the sound of minstrelsy, the old harper being seated on a stool beside the fireplace, and twanging his instrument with a vast deal more power than melody. Never did Christmas board display a more goodly and gracious assemblage of countenances: those who were not handsome were, at least, happy; and happiness is a rare improver of your hard-favoured visage. I always consider an old English family as well worth studying as a collection of Holbein's portraits or Albert Durer's prints. There is much antiquarian lore to be acquired; much knowledge of the physiognomies of former times. Perhaps it may be from having continually before their eyes those rows of old family portraits, with which the mansions of this country are stocked; certain it is, that the quaint features of antiquity are often most faithfully perpetuated in these ancient lines; and I have traced an old family nose through a whole picture gallery, legitimately handed down from generation to generation, almost from the time of the Conquest. Something of the kind was to be observed in the worthy company around me. Many of their faces had evidently originated in a Gothic age, and been merely copied by succeeding generations; and there was one little girl, in particular, of staid demeanour, with a high Roman nose, and an antique vinegar aspect, who was a great favourite of the Squire's, being, as he said, a Bracebridge all over, and the very counterpart of one of his ancestors who figured in the court of Henry VIII.The parson said grace, which was not a short familiar one, such as is commonly addressed to the Deity, in these unceremonious days; but a long, courtly, well-worded one of the ancient school. There was now a pause, as if something was expected; when suddenly the butler entered the hall with some degree of bustle: he was attended by a servant on each side with a large wax-light, and bore a silver dish, on which was an enormous pig's head decorated with rosemary, with a lemon in its mouth, which was placed with great formality at the head of the table. The moment this pageant made its appearance, the harper struck up a flourish; at the conclusion of which the young Oxonian, on receiving a hint from the Squire, gave, with an air of the most comic gravity, an old carol, the first verse of which was as follows:—Caput apri deferoReddens laudes Domino.The boar's head in hand bring I,With garlands gay and rosemary.I pray you all synge merilyQui estis in convivio.Though prepared to witness many of these little eccentricities, from being apprised of the peculiar hobby of mine host; yet, I confess, the parade with which so odd a dish was introduced somewhat perplexed me, until I gathered from the conversation of the Squire and the parson that it was meant to represent the bringing in of the boar's head: a dish formerly served up with much ceremony, and the sound of minstrelsy and song, at great tables on Christmas day. "I like the old custom," said the Squire, "not merely because it is stately and pleasing in itself, but because it was observed at the College of Oxford, at which I was educated. When I hear the old song chanted, it brings to mind the time when I was young and gamesome—and the noble old college-hall—and my fellow-students loitering about in their black gowns; many of whom, poor lads, are now in their graves!"The parson, however, whose mind was not haunted by such associations, and who was always more taken up with the text than the sentiment, objected to the Oxonian's version of the carol; which he affirmed was different from that sung at college. He went on, with the dry perseverance of a commentator, to give the college reading, accompanied by sundry annotations: addressing himself at first to the company at large; but finding their attention gradually diverted to other talk, and other objects, he lowered his tone as his number of auditors diminished, until he concluded his remarks, in an under voice, to a fat-headed old gentleman next him, who was silently engaged in the discussion of a huge plateful of turkey

Wondered.

Caravaggio, Nativity with St. Francis and St. Lawrence, 1609

Luke Chapter 2

1 And it came to pass in those days, that there went out a decree from Caesar Augustus, that all the world should be taxed.

2 (And this taxing was first made when Cyrenius was governor of Syria.)

3 And all went to be taxed, every one into his own city.

4 And Joseph also went up from Galilee, out of the city of Nazareth, into Judaea, unto the city of David, which is called Bethlehem; (because he was of the house and lineage of David:)

5 To be taxed with Mary his espoused wife, being great with child.

6 And so it was, that, while they were there, the days were accomplished that she should be delivered.

7 And she brought forth her firstborn son, and wrapped him in swaddling clothes, and laid him in a manger; because there was no room for them in the inn.

8 And there were in the same country shepherds abiding in the field, keeping watch over their flock by night.

9 And, lo, the angel of the Lord came upon them, and the glory of the Lord shone round about them: and they were sore afraid.

10 And the angel said unto them, Fear not: for, behold, I bring you good tidings of great joy, which shall be to all people.

11 For unto you is born this day in the city of David a Saviour, which is Christ the Lord.

12 And this shall be a sign unto you; Ye shall find the babe wrapped in swaddling clothes, lying in a manger.

13 And suddenly there was with the angel a multitude of the heavenly host praising God, and saying,

14 Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace, good will toward men.

15 And it came to pass, as the angels were gone away from them into heaven, the shepherds said one to another, Let us now go even unto Bethlehem, and see this thing which is come to pass, which the Lord hath made known unto us.

16 And they came with haste, and found Mary, and Joseph, and the babe lying in a manger.

17 And when they had seen it, they made known abroad the saying which was told them concerning this child.

18 And all they that heard it wondered at those things which were told them by the shepherds.

24 December 2023

Tchaikovsky, Symphony No. 1 in G minor, Op. 13, Winter Daydreams

The Arctic Philharmonic, conducted by Eivind Gullberg Jensen, perform the opening, Allegro Tranquillo ...

Probable.

While Christmas Eve is the night par excellence of the supernatural, the whole season of the Twelve Days is charged with it. It is hard to see whence Shakespeare could have got the idea which he puts into the mouth of Marcellus in “Hamlet”:—

Some say that ever ‘gainst that season comesWherein our Saviour's birth is celebrated,The bird of dawning singeth all night long;And then, they say, no spirit dare stir abroad;The nights are wholesome; then no planets strike,No fairy takes, nor witch hath power to charm,So hallow'd and so gracious is the time.

Against this is the fact that in folk-lore Christmas is a quite peculiarly uncanny time. Not unnatural is it that at this midwinter season of darkness, howling winds, and raging storms, men should have thought to see and hear the mysterious shapes and voices of dread beings whom the living shun.

Throughout the Teutonic world one finds the belief in a “raging host” or “wild hunt” or spirits, rushing howling through the air on stormy nights. In North Devon its name is “Yeth (heathen) hounds”; elsewhere in the west of England it is called the “Wish hounds.” It is the train of the unhappy souls of those who died unbaptized, or by violent hands, or under a curse, and often Woden is their leader. At least since the seventeenth century this “raging host” (das wüthende Heer) has been particularly associated with Christmas in German folk-lore, and in Iceland it goes by the name of the “Yule host.”

In Guernsey the powers of darkness are supposed to be more than usually active between St. Thomas's Day and New Year's Eve, and it is dangerous to be out after nightfall. People are led astray then by Will o’ the Wisp, or are preceded or followed by large black dogs, or find their path beset by white rabbits that go hopping along just under their feet.

In England there are signs that supernatural visitors were formerly looked for during the Twelve Days. First there was a custom of cleansing the house and its implements with peculiar care. In Shropshire, for instance, “the pewter and brazen vessels had to be made so bright that the maids could see to put their caps on in them—otherwise the fairies would pinch them, but if all was perfect, the worker would find a coin in her shoe.” Again in Shropshire special care was taken to put away any suds or “back-lee” for washing purposes, and no spinning might be done during the Twelve Days. It was said elsewhere that if any flax were left on the distaff, the Devil would come and cut it.

The prohibition of spinning may be due to the Church's hallowing of the season and the idea that all work then was wrong. This churchly hallowing may lie also at the root of the Danish tradition that from Christmas till New Year's Day nothing that runs round should be set in motion, and of the German idea that no thrashing must be done during the Twelve Days, or all the corn within hearing will spoil. The expectation of uncanny visitors in the English traditions calls, however, for special attention; it is perhaps because of their coming that the house must be left spotlessly clean and with as little as possible about on which they can work mischief. Though I know of no distinct English belief in the return of the family dead at Christmas, it may be that the fairies expected in Shropshire were originally ancestral ghosts. Such a derivation of the elves and brownies that haunt the hearth is very probable.

Clement A. Miles, from Christmas In Ritual and Tradition, Christian and Pagan

Misrule.

Chambers, Collecting the Yule Log, 1864

Every one has heard of the matchless “Lord of Misrule” (also known as the “Abbot of Unreason” and the “Master of Merry Disports”), who, attended by his mock court, king's jester and grotesquely masked revelers, visited the castles of lords and princes to entertain them with strange antics and uproarious merriment. His reign lasted until Twelfth Night, during which period he was treated as became a genuine monarch, being feted and feasted, with all his train, and having absolute authority over individuals and state affairs.

The great event of the evening, after the holiday feast, was the bringing in of the famous yule log, which was often the entire root of a tree. Much ceremony and rejoicing attended this performance, as it was considered lucky to help pull the rope. It was lighted by a person with freshly washed hands, with a brand saved from the last year's fire, and was never allowed to be extinguished, as the witches would then come down the chimney.

The presence of a barefooted or cross-eyed individual or of a woman with flat feet was thought to foretell misfortune for the coming year.

The games of “snap dragon” and “hot cockles” are supposed to be relics either of the “ordeal by fire” or of the days of the ancient fire-worshippers. The former consists of snatching raisins from a bowl of burning brandy or alcohol, and the latter of taking frantic bites at a red apple revolving rapidly upon a pivot in alternation with a lighted taper.

Christmas carols are commemorative of the angels' song to the shepherds on the plains of Bethlehem, and are seldom heard in America save by the surpliced choirs of the Episcopal churches. The English “waits,” or serenaders, who sang under the squires' windows in hopes of receiving a “Christmas box,” unconsciously add a touch of romance and picturesqueness to the associations of the season. For upon the frosty evening air arose such strains as—

“Awake! glad heart! arise and sing!It is the birthday of thy King!”

Or—

“God rest you, merry gentlemen!Let nothing you dismay,For Jesus Christ, our Savior,Was born upon this day.”

Bertha Herrick, from Myths and Legends of Christmastide

King's.

The 1954 BBC broadcast of Nine Lessons and Carols from King's College Cambridge, directed by Boris Ord ...

Revels.

The party now broke up for the night with the kind-hearted old custom of shaking hands. As I passed through the hall, on the way to my chamber, the dying embers of the Yule-clog still sent forth a dusky glow; and had it not been the season when "no spirit dares stir abroad," I should have been half tempted to steal from my room at midnight, and peep whether the fairies might not be at their revels about the hearth.

My chamber was in the old part of the mansion, the ponderous furniture of which might have been fabricated in the days of the giants. The room was panelled with cornices of heavy carved-work, in which flowers and grotesque faces were strangely intermingled; and a row of black-looking portraits stared mournfully at me from the walls. The bed was of rich though faded damask, with a lofty tester, and stood in a niche opposite a bow-window. I had scarcely got into bed when a strain of music seemed to break forth in the air just below the window. I listened, and found it proceeded from a band, which I concluded to be the waits from some neighbouring village. They went round the house, playing under the windows. I drew aside the curtains, to hear them more distinctly. The moonbeams fell through the upper part of the casement, partially lighting up the antiquated apartment. The sounds, as they receded, became more soft and aerial, and seemed to accord with quiet and moonlight. I listened and listened—they became more and more tender and remote, and, as they gradually died away, my head sank upon the pillow and I fell asleep.

Washington Irving, from "Christmas Eve," found in Geoffrey Crayon's Sketchbook

23 December 2023

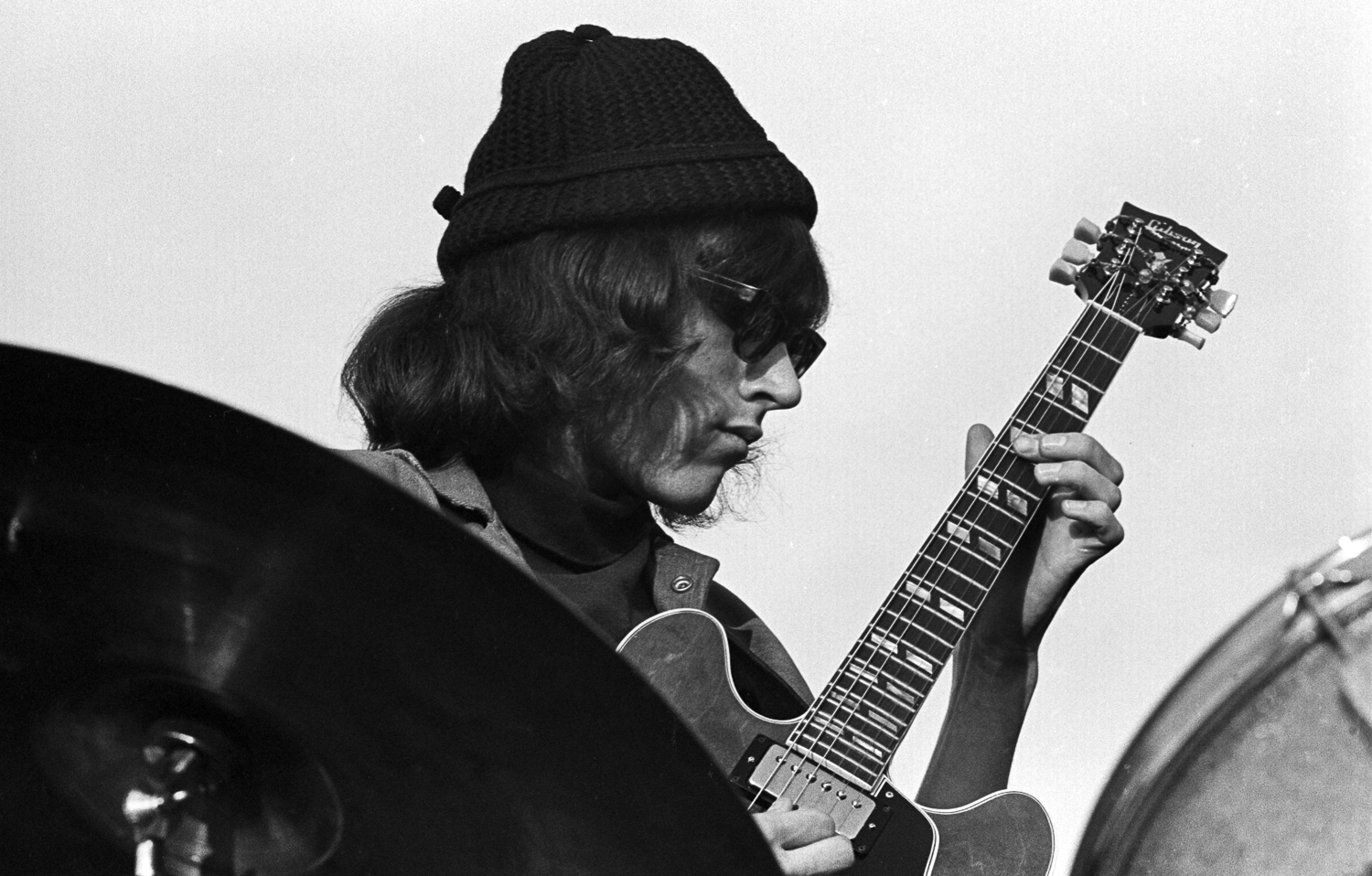

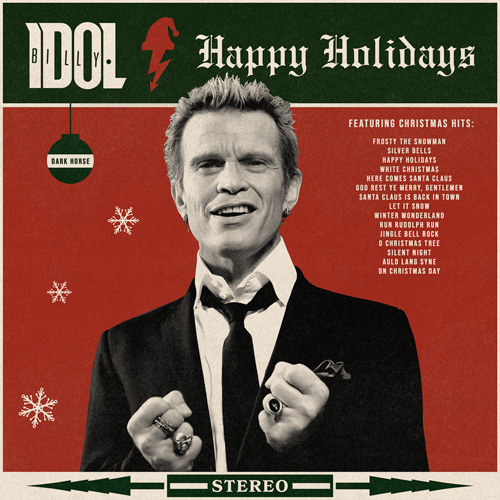

Happy Birthday, Kaukonen

Jorma Kaukonen was born on this day in 1940.

"I Am the Light of This World"

Hot Tuna in 1976 ...

Solo in 2013 ...

Vivaldi, Four Seasons

Recomposed by Max Richter, a reworking of Vivaldi's Four Seasons. This is the Largo in E♭ major from Concerto No. 4 in F minor, Op. 8, RV 297, "Winter" ...

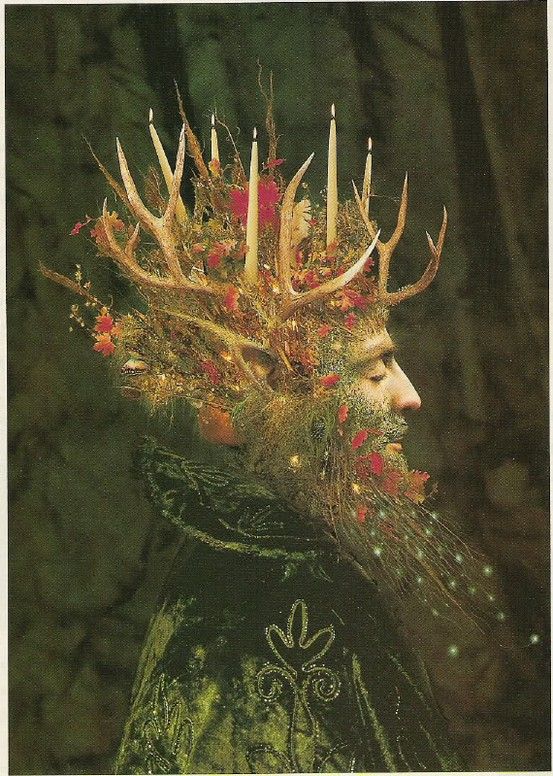

Darksome.

Kerbow, The Yule King, n/d

The darksome Holly King rules the dark half of the year from Midsummer to Midwinter.

22 December 2023

Prowl.

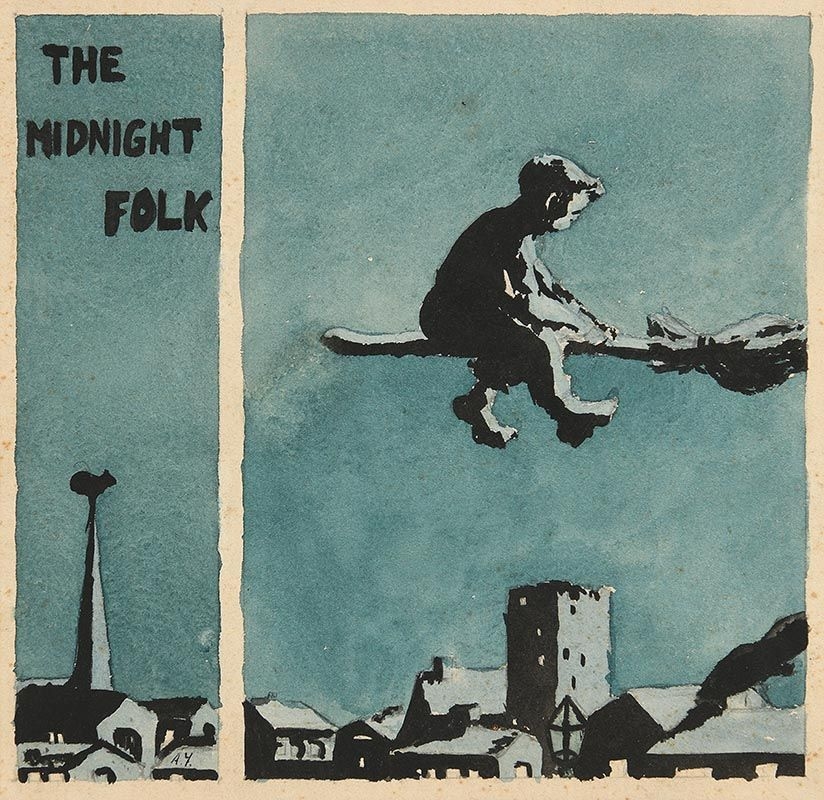

When the midnight strikes in the belfry dark

And the white goose quakes at the fox’s bark,

We saddle the horse that is hayless, oatless,

Hoofless and pranceless, kickless and coatless,

We canter off for a midnight prowl

Whoo-hoo-hoo, says the hook-eared owl.

John Masefield, from The Midnight Folk

Heartily.

This week in 1777, George Washington led the remnants of his nearly vanquished, but heartily determined, Continentals to Valley Forge for the winter.

Valley Forge: A Winter Encampment (directly below) is an old orientation film shown at Valley Forge National Historical Park from 1993 until 2020 when it was replaced by the current film (furthest below) Determined to Persevere: The Valley Forge Encampment ...

Unsung Heroes of Valley Forge ...

Light.

During Hanukkah 1931, Rachel Posner, wife of Rabbi Dr. Akiva Posner, took this photo of the family Hanukkah menorah from the window ledge of the family home looking out on to the building across the road decorated with Nazi flags.

On the back of the photograph, Rachel Posner wrote (translated from German) ...

"Death to Judah"So the flag says"Judah will live forever"So the light answers

Ben Maton

Ben Maton guides us through the English countryside, moldy old piles, and ancient Christmas music ...

Advent I ...

Advent II ...

More "good old-fashioned escapism" ...

Circumstances.

I feel a good deal of hesitation about telling you this story of my own. You see it is not a story like the other stories that I have been telling you, or rather that Teddy Biffles, Mr. Coombes, and my uncle have been telling you: it is a true story. It is not a story told by a person sitting round a fire on Christmas Eve, drinking whisky punch: it is a record of events that actually happened.

Indeed, it is not a 'story' at all, in the commonly accepted meaning of the word: it is a report. It is, I feel, almost out of place in a book of this kind. It is more suitable to a biography, or an English history.

There is another thing that makes it difficult for me to tell you this story, and that is, that it is all about myself. In telling you this story, I shall have to keep on talking about myself; and talking about ourselves is what we modern-day authors have a strong objection to doing. If we literary men of the new school have one praiseworthy yearning more ever present to our minds than another it is the yearning never to appear in the slightest degree egotistical.

I myself, so I am told, carry this coyness—this shrinking reticence concerning anything connected with my own personality, almost too far; and people grumble at me because of it. People come to me and say -

"Well, now, why don't you talk about yourself a bit? That's what we want to read about. Tell us something about yourself."

But I have always replied, "No." It is not that I do not think the subject an interesting one. I cannot myself conceive of any topic more likely to prove fascinating to the world as a whole, or at all events to the cultured portion of it. But I will not do it, on principle. It is inartistic, and it sets a bad example to the younger men. Other writers (a few of them) do it, I know; but I will not—not as a rule.

Under ordinary circumstances, therefore, I should not tell you this story at all. I should say to myself, "No! It is a good story, it is a moral story, it is a strange, weird, enthralling sort of a story; and the public, I know, would like to hear it; and I should like to tell it to them; but it is all about myself—about what I said, and what I saw, and what I did, and I cannot do it. My retiring, anti-egotistical nature will not permit me to talk in this way about myself."

But the circumstances surrounding this story are not ordinary, and there are reasons prompting me, in spite of my modesty, to rather welcome the opportunity of relating it.

Jerome K. Jerome, from "Told After Supper"

Happy Birthday, Puccini

Giacomo Puccini was born on this day in 1858.

Elina Garanča performs "Vissee dArte," from Act II of Tosca, with the Symphony Orchestra of the Volksoper Vienna, directed by Karel Mark Chichon ...

21 December 2023

Charcoal-Based.

Archaeologists have long been puzzled by the exact age of Paleolithic cave art in Europe especially in the Franco-Cantabrian region with hundreds of decorated caves because the creation of this parietal art (paintings, drawings and engravings) is closely tied to the appearance of first modern humans in Europe and their ways of life. The Dordogne region, one of the richest regions in terms of Paleolithic cave art in the world with more than 200 cave sites, is currently known to provide figures of cave art solely made with mineral coloring matters that cannot be dated directly. Using in-situ non-invasive Raman spectroscopy combined with portable X-ray fluorescence analysis as well as visible and infrared imaging of the decor of the Font-de-Gaume cave, we show the presence of a large number of charcoal-based Paleolithic figures besides others made of iron and manganese oxides in the main galleries for the first time. The creation periods of the cave art at Font-de-Gaume are mainly attributed to the Magdalenian period and probably more complicated constituted of at least two creation phases than commonly established as shown by the direct or partial superimposition of carbon-based and iron- and/or manganese-based figures. Our new results contribute to a better understanding of the organisation of the ornamentation and thus of the imaginary language of our Prehistoric ancestors. The discovery opens new research possibilities for re-reading of the complex panels and absolute radiocarbon dating.

Quirky.

Laurens, Faust, n/d

People who read too many books get quirky. We can't have too much eccentricity or it would bankrupt us. Market research depends on people behaving as if they were all alike.

John Taylor Gatto, from The Underground History of American Education: An Intimate Investigation Into the Prison of Modern Schooling

Life.

Never, our archaeologists of the future will surely conclude, was any generation of men intent upon the pursuit of happiness more advantageously placed to attain it, who yet, with seeming deliberation, took the opposite course—toward chaos, not order; toward breakdown, not stability; toward death, destruction and darkness, not life, creativity and light.

Malcom Muggeridge

From a classic episode of Firing Line, Buckley and Muggeridge discuss the topic, "How Does One Find Faith?" ...

Blake, "Walking in the Air"

Birdy covers Howard Blake's "Walking in the Air," from The Snowman ...

Don't miss George Winston's treatment on Forest.

Brooding.

I woke from a dead sleep in dead darkness to hear… what? What can I hear? It sounded like a ball bearing or a marble rolling on the bare floor above my head. It rolled hard on hard then hit the wall. Then it rolled again in the other direction. This might not have mattered except that the other direction was upwards. Things can come loose and roll downwards, but they cannot come loose and roll up. Unless someone…

That thought was so unwelcome that I dismissed it along with the law of gravity. Whatever was rolling over my head must be a natural dislodging. The house was draughty and unused. The attics were under the eaves where any kind of weather might get in. Weather or an animal. Remember the bats. I pulled the covers up to my eyebrows and pretended not to listen.

There it was again: hard on hard on hit on pause on roll.

I waited for sleep, waiting for daylight.

We are lucky, even the worst of us, because daylight comes.

It was a brooding day that 21st of December. The shortest day of the year. Coffee, coat on, car keys. Shouldn't I just check the attic?

Jeanette Winterson, from "Dark Christmas"

Half-Lit.

At solstice, the woods were bright in a snowy way, the sky pearl gray above the stately maples and gnarled burr oaks. An Alaskan marooned in the urban Midwest, it took me years to find this nearby patch of relatively undisturbed land where I can sense the power of wildness. Now I go there often, watching the seasons unfold their changeful unchanging patterns in the increasingly familiar forest.

I especially like to walk among the sleeping trees in the half-lit silence of winter dawns. The trail I follow winds and twists, new patches of mixed woodland appearing at every turn. That morning, I reached a point where the path turns sharply left to follow a small ravine. In spring, ephemeral ponds—lively with salamanders, loud with frogs—form in the creases of the forest there. But in frozen winter, I expected nothing beyond silence and wind.

So I did not see them at first, three deer beside three empty larches. When I made them out—gray-dun hides against a gray-dun world—they were motionless, white tails aloft like flags of distress. I stopped in my tracks, thinking how lucky I was to meet the animal my Celtic forebears called the spirit of wildness on that auspicious day.

I often encounter deer on my morning walks. The woods are close enough to roads and homes that we humans are no strangers to them. But like any animal of the suburban wild—squirrel or opossum or raccoon—the deer keep their distance. An instant after they see me, they bound silently away, their white-flag tails on high alert.

But this morning, the deer only stared at me across the ravine. To the left stood a tall stately doe; to the right, an older heavier one; in the center, one of the previous spring’s fawns, all gangly adolescence. Huge soft ears held high, they cast dark liquid gazes at me.

And did not run.

Desire burst in my heart: to speak to the deer, to tell them how beautiful they were, to thank them for bringing wildness to the edge of the vast city. To speak from my heart, my own little wild heart, to theirs. To celebrate the season with them.

But I stood silent, for I do not speak the language of deer. I stared silently at them, awaiting the inevitable flight. But moments stretched out like fingers of light from the rising sun, and the deer did not run away.

Then, for no reason I can easily explain, I began to sing, my voice loud in the silent forest. A plaintive minor-keyed medieval song sprang to my lips, a holiday carol I’ve known since girlhood. Lo how a rose e’er blooming, from tender stem hath sprung. . . It came a floweret bright, amidst the snows of winter, when half-spent was the night.

I thought the sound of my voice would frighten the deer away, but I wanted to speak to them, and music seemed the only way.

Just as I expected, they began to move. But not swiftly. And not into the forest. Not away from me at all.

No. One slow step at a time, the deer moved towards me.

When I started singing, they were perhaps fifty feet away. By the time I began the second verse, they were half that distance. By the time I finished the song, the deer stood just across the ravine.

In the sudden silence at the song’s end, three tails went suddenly up again, sounding a silent alert. So I began another song. Tails went down, ears moved slightly forward. Dawn light emblazoned lemon and melon stripes upon the snow as three deer listened to carol after carol after carol.

A quarter-hour passed and still they did not move. I kept singing.

It was not the deer but me who ended our encounter. The sky had moved from pearl to sherbet to azure, and I had promises to keep. I thanked the deer for listening to my dawn chorus. The sound of my words shook them awake. Tails went up, forelegs tucked up, and in an instant they were gone.

In the silence, I stared into the gray forest. Only a few months earlier, standing below a high-massed mountain glacier I have known since childhood, now shrinking fast away, its ancient snows surging down to the gray sea in cold torrents, I had felt overwhelmed with hopelessness. Do we only take from nature, giving nothing in return? If so, what use are we? Why should the universe continue to provide for us, if we are such ungrateful children?

But there on the edge of a tiny ravine, hope washed over me like light. Perhaps there is a reason for our being. Perhaps what we give our lovely blue earth is song. Beauty. Art. Perhaps that is the reason we were created: to entertain the universe. Perhaps the great spirit is amused and touched, thrilled and delighted by our childlike creativity. Today we leave art to the professionals: to those with beautiful voices and firm bodies and exciting visions. But perhaps art is not frozen moments of perfection but the process of creation itself. Perhaps we were put here to pleasure the world, making art as spontaneously and joyfully as children drawing great yellow suns with wax crayons. Perhaps we should all be singing more, and dancing, and painting with bright colors, and chanting out poems. Perhaps we silly wonderful amateurs most please the universe when we act that way.

Patricia Monaghan

Mum.

Mum Chenoweth’s Oatmeal Cherry Cookies

Heat oven to 350 degrees.

Mix:

- 1 cup Crisco ("butter flavor" is the best)

- 1 cup firmly packed brown sugar

- ½ cup sugar

This will get fluffy.

Then add:

- 2 eggs

- 1 teaspoon vanilla

This will incorporate, at which time you will add:

- 1 teaspoon baking soda

- ½ teaspoon ground cinnamon

- ½ teaspoon salt

- 1 and ½ cup of all-purpose flour

Once this is a paste or mixture, add:

- 3 cups of old fashioned oats

- 1 and ½ cups of dried cherries (or cranberries or dried blueberries or raisins). If you like, soak the dried fruit in rum.

Spoon onto ungreased cookie sheet and baked for 12 minutes.

Most important: After the cookies have cooled, they go into a brown paper bag for storage.

Thanks, Mum.

Dark.

John F. Carlson, Woodland Silence, 1903

To go in the dark with a light is to know the light.

To know the dark, go dark. Go without sight,

and find that the dark, too, blooms and sings,

and is traveled by dark feet and dark wings.

Wendell Berry

19 December 2023

Expedition.

In the olden days there lived in Kvam a hunter whose name was Peter Gynt, and who was always roaming about in the mountains after bears and elks, for in those days there were more forests on the mountains than there are now, and consequently plenty of wild beasts.

One day, shortly before Christmas, Peter set out on an expedition. He had heard of a farm on Doorefell which was invaded by such a number of trolls every Christmas Eve that the people on the farm had to move out, and get shelter at some of their neighbours'. He was anxious to go there, for he had a great fancy to come across the trolls, and see if he could not overcome them. He dressed himself in some old ragged clothes, and took a tame white bear which he had with him, as well as an awl, some pitch and twine. When he came to the farm he went in and asked for lodgings.

"God help us!" said the farmer. "We can't give you any lodgings. We have to clear out of the house ourselves soon and look for lodgings, for every Christmas Eve we have the trolls here."

But Peter thought he should be able to clear the trolls out,—he had done such a thing before; and then he got leave to stay, and a pig's skin into the bargain. The bear lay down behind the fireplace, and Peter took out his awl and pitch and twine, and began making a big, big shoe, which it took the whole pig's skin to make. He put a strong rope in for lacings, that he might pull the shoe tightly together, and, finally, he armed himself with a couple of handspikes.

Shortly he heard the trolls coming ...

Peter Christen Asbjörnsen, from "'Round the Yule-Log"

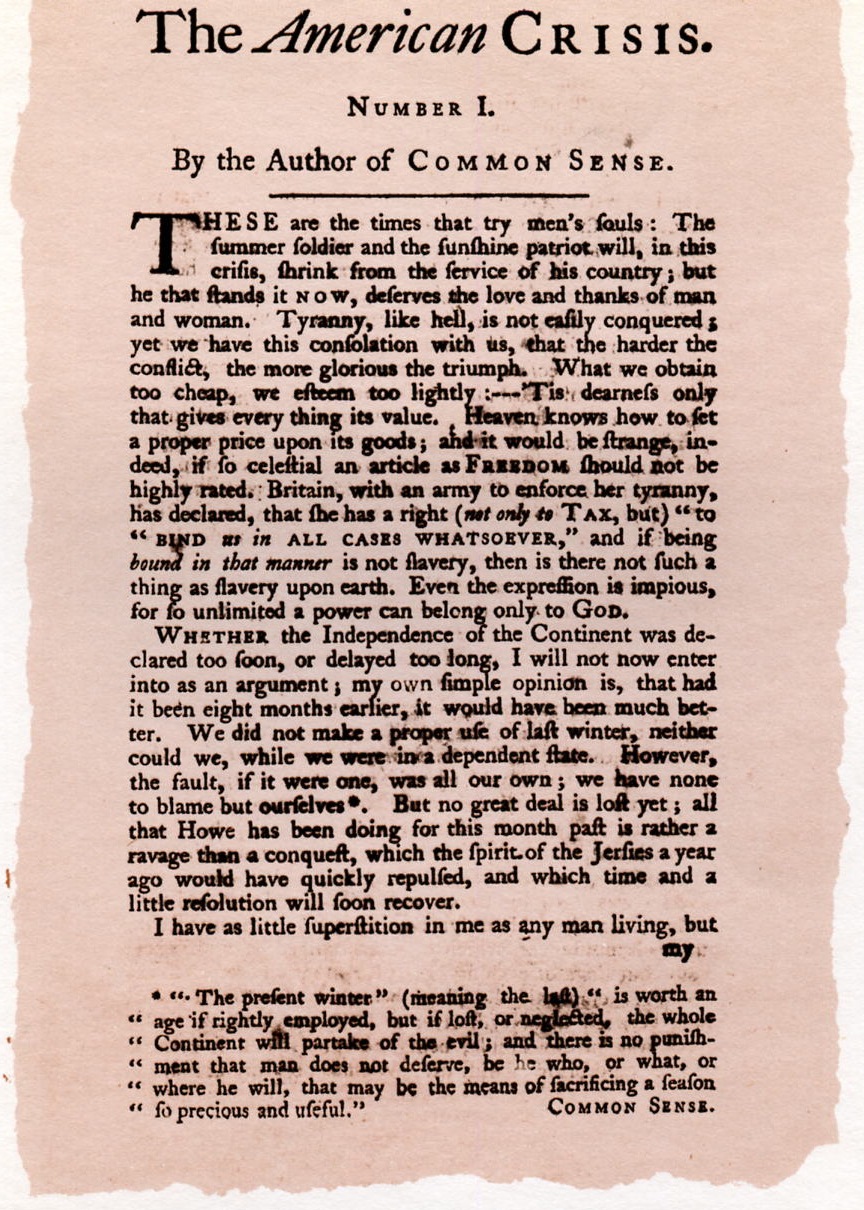

Published.

Thomas Paine published the first of his American Crisis pamphlets on this day in 1776.

The AMERICAN CRISIS.By the Author of COMMON SENSEThese are the times that try men's souls: The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of his country but he that stands it NOW, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman. Tyranny, like hall, is not easily conquered; yet we have this consolation with us, that the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph. What we obtain, too cheap, we esteem too lightly:—'Tis dearness only that gives every thing its value. Heaven knows how to set a proper price upon its goods; and it wou?d be strange indeed, if so celestial an article as Freedom should not be highly rated. Britain, with an army to enforce her tyranny, has declared, that she has a right ( (not only to TAX) but “to BIND us in ALL CASES WHATSOEVER,” and if being bound in that manner is not slavery, then is there not such a thing as slavery upon earth. Even the expression is impious, for so unlimited a power can belong only to God.Whether the Independence of the Continent was declared too soon, or delayed too long, I will not now enter into as an argument; my own simple opinion in that had it been eight months earlier, it would have been much better. We did not make a proper use of last winter, neither could we while we were in a dependent state. However, the fault, if it were one, was all our own; we have none to blame but ourselves.* But no great deal is lost yet; all that Howe has been doing for this month past is rather a ravage than a conquered which the spirit of the Jersies a year ago would have quickly repulsed, and which time and a little resolution with soon recover, and which time and a little resolution will soon recover.* “ The present ”, (meaning the last) “is worth an if rightly employed, but if lost, or neglected the will partake of the evil, and there is no that does not deserve who or what or where be will, that may be the means of sacrificeing a to precious and ”. Common Sense.I have as little superstition in me as any man living, but my secret opinion has ever been, and still is, that God almighty will not give up a people to military destruction, or leave them unsupportedly to perish, who had so earnestly and so repeatedly fought to avoid the calamities of war, by every decent method which seldom could invent. Neither have I so much of the is me, as to suppose, that He has relinquished the government of the world, and given us up to the care of devils; and as I do not, I cannot see on what ground the king of Britain can look up to Heaven for help against us: A common murderer, a highwayman, or a house-breaker, has as good a pretence as he.'Tis surprising to see how rapidly a panic will sometimes run through a country. All nations and ages have been subject to them; Britain has trembled like an ague at the report of a French fleet of flat-bottomed boats; and in the fourteenth century the whole English army, after ravaging the kingdom of France, was driven back like men petrified with fear; and this brave exploit was performed by a few broken forces collected and headed by a woman, Joan of Arc, Would, that Heaven might inspire some Jersey maid to spirit up her countrymen, and save her fair fellow sufferers from ravage and ravishment! Yet panics, in some cases, have their uses; they produce as much good as hurt. Their duration is always short; the mind soon grows through them, and acquires a firmer habit than before. But their peculiar advantage is, that they are the touchstones of sincerity and hypocrisy, and bring things and men to light, which might otherwise have lain forever undiscovered. In fact, they have the same effect on secret traitors, which an imaginary apparition would upon a private murderer. They lift out the hidden thoughts of man, and hold them up in public to the world. Many a disguised Tory has lately shewn his head, that shall penitentially solemnize with curses the day on which Howe arrived upon the Delaware.As I was with the troops at fort Lee, and marched with them to the edge of Pennsylvania, I am well acquainted with many circumstances, which those, who lived at a distance, know but little or nothing of. Our situation there was exceedingly cramped, the place being on a narrow neck of land between the North-river and the Hackinfack. Our force was inconsiderable, being not one fourth so great as Howe could bring against us. We had no army at hand to have relieved the garrison, had we shut ourselves up and stood on the defence. Our ammunition, light artillery, and the best part of our stores had been removed upon the apprehension that Howe would endeavour to penetrate the Jersies, in which case fort Lee could be of no use to us; for it must occur to every thinking man, whether in the army or not, that these kind of field forts are only for temporary purposes, and lasts in use no longer than the enemy directs his force against the particular object, which such force are raised to defend. Such was our situation and condition at fort Lee on the morning of the 20th of November, when an officer arrived with information, that the enemy with 200 boats had landed about seven or eight miles above: Major-General Green, who commanded the garrison, immediately ordered them under arms, and tent express to his Excellency General Washington, at the town of Hackinsack, distant by the way of the Perry fix miles. Our first object was to secure the bridge over the Hackinsack, which laid up the river between the enemy and or, about six miles from us and three from them. General Washington arrived in about three quarters of an hour, and marched at the head of the troops towards the bridge, which expected we should have a ; However they did not to dispute it with us and the went over the bridge, the , except some which passed at a mill by a small creek, between the bridge and the , and made their way grounds The simple object was to being of of the , and to march them on they could by the Jersey or Pennsylvania militis, to as to be to make a stand. We said four days at Newark, collected in our out posts with fame of the Jersey militia, and marched out twice to meet the enemy on information of their being advancing, though our numbers were greatly inferior to theirs. Howe, in my little opinion, committed a great error in general ship, in not throwing a body of forces off from Staten. If and through Amboy, by which means he might have seized all our stores at Brunswick, and intercepted our march into Pennsylvania. But, if we believe the power of hell to be limited, we must likewise believe that their agents are under some providential controul.I shall not now attempt to give all the particulars of our retreat to the Delaware, suffice it for the present to say, that both officers and men, though greatly harassed and fatigued, frequently without self, covering or provision, the inevitable consequences of a long retreat, bore it with a manly and martial spirit. All their wishes were one, which was, that the country would turn out and help them to drive the enemy back. Voltaire has remarked, that king William never appeared to full advantage but in difficulties and in action; the same remark may be made on General Washington for the character fits him. There is a natural fannels in some minds which cannot be unlocked by trifles, but which, when unlocked discovers a cabinet of fortitude, and I reckon it among those kind of public blessing, which we do not immediately fee, that God hath blest him with uninterrupted health, and gives him a mind that can even flourish upon care.I shall conclude this paper with some miscellaneous remarks on the slate of our affairs; and shall begin with asking the following question, Why is it that the enemy hath left the New England provinces, and made those middle once the fear of war? The answer is easy, New England is not infested with Tories, and we are. I have been under in raising the cry against these men, and used numberless arguments to shew them their danger, but it without do to sacrifice a world to either their folly or . The period is now arrived, in which either they or we must change our sentiments, or one or both must fall. And what is a Tory? Good GOD! what is he? I should not be afraid to go with a hundred Whigs against a thousand Tories, were they to attempt to get into arms. Every Tory is a coward, for a servile, slavish, self-interested fear is the foundation of Toryism; and a man under such influence, though he may be cruel, never can be brave.But before the line of irrecoverable separation be drawn between us, let us reason the matter together: Your conduct is an invitation to the enemy, yet not one in a thousand of you has heart enough to join him. Howe is as much deceived by you as the American cause is injured by you. He expects you will all take up arms, and flock to his standard with muskets on your shoulders, Your opinions are of no use to him, unless you support him personally; for 'tis soldiers, and not Tories, that he wants.I once felt all that kind of anger, which a man ought to feel, against the mean principles that are held by the Tories. A noted one, who kept a tavern at Amboy, was standing at his door, with as pretty a child in his hand, about eight or nine years old, as most I ever saw, and after speaking his mind as freely as he thought was prudent, finished with this unfartherly expression, “ Well! give me peace in my day.” Not a man lives on the Continent but fully believes that a separation must some time or other finally take place, and a generous parent would have said, “ If there must be trouble, let it be in my day, that my child may have peace;” and this single reflection, well applied, is sufficient to awaken every man to duty. Not a place upon earth might be so happy as America. Her situation is remote from all the wrangling world, and she has nothing to do but to trade with them. A man may easily distinguish in himself between temper and principle, and I am as confident, as I am that God governs the world, that America will never be happy till she gets clear of foreign dominion. Wars, without ceasing, will break out till that period arrives, and the Continent must in the end be conquerors; for, though the flame of liberty may sometimes cease to shine, the coal never can expire.America did not, nor does not, want force; but she wanted a proper application of that force. Wisdom is not the purchase of a day, and it is no wonder that we should err at first setting off. From an excess of tenderness, we were unwilling to raise an army, and trusted our cause to the temporary defence of a well meaning militia. A summers experience has now taught us better, yet with those troops, while they were collected, we were able to set bounds to the progress of the enemy, and, thank God! if they are again assembling. I always considered a militia as the best troops in the world for a sudden exertion, but they will not do for a long campaign. How, it is probable, will make an attempt on this city; should he fail on this side the Delaware, he is ruined; if he succeeds, our cause is not ruined. He makes all on his side against a part on ours; admitting he succeeds, the consequence will be, that armies from both ends of the Continent will march to assist their suffering friends in the middle States; for he cannot go every where, it is impossible. I consider Howe as the greatest enemy the Tories have; he is bringing a war into their country, which, had it not been for him and partly for themselves, they had been clear of. Should he now be expelled, I wish, with all the devotion of a Christian, that the names of Whig and Tory may never more be mentioned; but should the Tories give him encouragement to come, a gauge of sorrow draw forth the fear of comparison nothing can reach the heart that is fleeted with prejudice.Quitting this class of men, I turn with the warm ardour of a friend to those who have nobly stood yet determined to stand the matter out; I call not upon a few, but upon all; not on THIS state or THAT truth but on EVERY state; up and help us; lay your shoulders to the wheel; better have too much force than too little, when so great an object is at stake. Let it be told to the future world, that in the depth of winter, when nothing but hope and virtue could survive, that the city and the country, alarmed at one common danger, come forth to meet and to repulse it. Say not, that thousands are gone, turn out your tens of thousands; throw not the bur hen of the day upon Providence, but “ Shew your faith by your works, ” that God may bless you. It matters not where you live, or what rank of life you hold, the evil or the blessing will reach you all. The far and the near, the home counties and the back, the rich and the poor, shall suffer or rejoice alike. The heart that feels not now, is dead: The blood of his children shall curse his cowardice, who shrinks back at a time when a little might have saved the whole, and made them happy. I love the man that can smile in trouble, that can gather strength from distress, and grow brave by reflection. 'Tis the business of little minds to shrink; but he whose heart is firm, and whose conscience approves his conduct, will pursue his principles unto death. My own line of reasoning is to myself as strait and clear as a ray of light. Not all the treasures of the world, is far as I believe, could have induced me to support an offensive war, for I think it murder; But if a thief break into my house, burn and destroy my property, and kill or threaten to kill me, or those that are in it, and to “bind me in all cases whatsoever,” to his absolute will, am I to suffer it? What signifies it to me, whether he who does it, is a king) or a common man; my countryman or not my countryman; whether it is done by an individual villain, or an army of them? If we reason to the root of things we shall find no difference; neither can any just cause be assigned why we should punish in the one case, and pardon in the other. Let them call me rebel, and welcome, I feel no concern from it; but I should suffer the misery of devils, were I to make a whore of my soul by swearing allegiance to one, whose character is that of a , stupid, stubborn, worthless, brutish man. I conceive likewise a horrid idea in receiving mercy from a being, who as the last day shall be shrieking to the rocks and mountains to cover him, and fleeing with terror from the orphan, the widow and the slain of America.There are cases which cannot be overdone by language, and this is one. There are persons too who see not the full extent of the evil that threatens them; they solace themselves with hopes that the enemy, if they succeed, will be merciful. It is the madness of folly to expect mercy from those who have refused to do justice; and even mercy, where conquest is the object, is only a trick of war; The cunning of the fox is as murderous as the violence of the whose, and we ought to guard equally against both. Howe's first object is partly by threats and partly by promises, to terrify or seduce the people to deliver up their arms, and receive mercy. The ministry recommended the same plan to Gage, and this is what the Tories call making their peace; “ a peace which passeth all understanding ” indeed A peace which would be the immediate forerunner of a worse ruin than any we have yet thought of. Yet men of Pennsylvania, do reason upon those things? Were the back counties to give up their aims, they would fall an easy prey to the Indians, who are all armed: This perhaps is what some Tories would not be sorry for. Were the home counties to deliver up their arms, they would be exposed to the resentment of the back counties, who would then have it in their power to their defection at pleasure—And were any one State to give up its arms, that State must be garrisoned by all Howe's army of Britons and Hassians to preserve it from the anger of the rest. Mutual fear is a principal link in the chain of mutual love, and woe be to that State that breaks the compact Howe is mercifully inviting you to barbarous , and men must be either rogues or fools that will not see it. I dwell not upon the vapours of imagination; I bring reason to your ears; and in language are plain as A, B, C; hold up truth to your eyes.I thank God that I fear not. I see no real cause for fear. I know one situation well, and can see the way out of it. While our army was collected, Howe dared not risk a battle, and it is not credit to him that he decamped from the White Plains, and waited a mean opportunity to ravage the defenceless Jersies; but it is great credit to us, that, with an handful of men, we sustained an orderly retreat for near an hundred miles? brought off our ammunition, all our field pieces, the greatest part of our stores, and had four rivers to pass. None can say that our retreat was precipitate, for we were near three weeks in performing it, that the country might have time to come in. Twice we marched back to meet the enemy and remained out till dark. The sign of fear was not seen in our camp, and had not some of the cowardly and disaffected inhabitants spread false alarms through the country, the Jersies had never been ravaged. Once more we are again collected and collecting; our new army at both ends of the continent recruiting fast, and we shall be able to open the next campaign with sixty thousand men; well armed & cloathed. This is our situation, and who will may know it. By perseverance and fortitude have the prospect of a glorious issue, by cowardice and the sad choice of a variety of evils— a ravaged country—a depopulated city—habituations without safety, and slavery without hope—our homes turned into barracks and, and a future race to provide for whose fathers with all doubt of. Look on this picture, and weep over it and if there yet remains one thoughtless which who believes it not, let be if unlamented.Sold opposite the Court-House, Queen Street.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

About Me

- Rob Firchau

- "A man should stir himself with poetry, stand firm in ritual, and complete himself in music." -Gary Snyder

Think ...

SEARCH THIS BLOG

ARCHIVES

-

▼

2023

(2125)

-

▼

December

(165)

- Jethro Tull, "Wond'ring Aloud"

- Divine.

- Sphering.

- Bingo & Co., "Snow"

- Lore.

- Leadership.

- No title

- Sprung.

- Fayrfax, Missa Tecum Principium

- Red-Letter.

- Grace.

- Now.

- Happy Birthday, Matisse

- Matteis, "Alia Fantasia"

- Prod.

- Winter.

- Wonder.

- Done.

- Neale, "Good King Wenceslas"

- Haunted.

- Must.

- Sibelius, The Trees, Op. 75

- Wondered.

- Frank Sinatra, "Mistletoe and Holly"

- Flight.

- Tchaikovsky, Symphony No. 1 in G minor, Op. 13, Wi...

- Probable.

- Misrule.

- King's.

- Revels.

- Happy Birthday, Kaukonen

- Vivaldi, Four Seasons

- Darksome.

- Happy Birthday, Gibbs

- Prowl.

- No title

- Excellent.

- Heartily.

- Light.

- Ben Maton

- Circumstances.

- Hurray.

- Excellent.

- Happy Birthday, Puccini

- Charcoal-Based.

- Mark Isham, "A Tale of Two Cities"

- Quirky.

- Life.

- Blake, "Walking in the Air"

- Brooding.

- Half-Lit.

- Mum.

- Dark.

- Jethro Tull, "Ring Out, Solstice Bells"

- Expedition.

- Published.

- Leonid.

- Instant.

- Glorious.

- Excellent.

- 900-Year-Old.

- Is.

- Enjoy.

- Happy Birthday, Keith

- Published.

- Nothin'.

- Enforced.

- Premiered.

- Oldest-Known.

- Will.

- Power.

- Pernicious.

- Transfer.

- Story.

- Love.

- Desire.

- Excellent.

- Contented-Looking.

- True-Born.

- Basking.

- John Stewart, "Gold"

- Excellent.

- Preparations.

- Courage.

- Happy Birthday, Beethoven

- America.

- Happy Birthday, Simonon

- Vivaldi, Gloria, RV 589

- Art.

- Technique is the proof of your seriousness.Wallace...

- Beyond.

- Kindness.

- Happy Birthday, Scott

- Excellent.

- Simplicity.

- Sinatra's.

- Mute.

- Nothing.

- Happy Birthday, Sinatra

- Expected.

-

▼

December

(165)

CARL R. FIRCHAU (1884-1973)

"The strength of a man’s virtue should not be measured by his special exertions but by his habitual acts.” Blaise Pascal

REMEMBER

SUPPORT OUR TROOPS

JIM HARRISON

37. Beware, O wanderer, the road is walking too, said Rilke one day to no one in particular as good poets everywhere address the six directions. If you can’t bow, you’re dead meat. You’ll break like uncooked spaghetti. Listen to the gods. They’re shouting in your ear every second.

WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART

"When I am, as it were, completely myself, entirely alone and of good cheer – say travelling in a carriage or walking after a good meal, or during the night when I cannot sleep – it is on such occasions that my ideas flow best and most abundantly. Whence, and how, they come I know not ; nor can I force them. Those ideas that please me I retain in memory and am accustomed, as I have been told, to hum them to myself. If I continue in this way, it soon occurs to me how I may turn this dainty morsel to account, so as to make a good dish of it. That is to say, agreeable to the rules of counterpoint, to the peculiarities of various instruments etc. All this fires my soul, and, provided I am not disturbed, my subject enlarges itself, becomes methodised, and defined, and the whole, though it be long, stands almost complete and finished in my mind, so that I can survey it like a fine picture or a beautiful statue at a glance. Nor do I hear in my imagination the parts successively, but I hear them, as it were, all at once. What a delight this is, I cannot tell."

N.C. WYETH

Cold Maker, Winter, 1909

WILLIAM F. BUCKLEY JR.

J.R.R. TOLKIEN

"If more of us valued food and cheer and song above hoarded gold, it would be a merrier world."

IKKYU

JOHN MASEFIELD

"When the midnight strikes in the belfry dark/And the white goose quakes at the fox’s bark/We saddle the horse that is hayless, oatless/Hoofless and pranceless, kickless and coatless/We canter off for a midnight prowl/Whoo-hoo-hoo, says the hook-eared owl."

JOHN QUINCY ADAMS

"However tiresome to others, the most indefatigable orator is never tedious to himself. The sound of his own voice never loses its harmony to his own ear; and among the delusions, which self-love is ever assiduous in attempting to pass upon virtue, he fancies himself to be sounding the sweetest tones."

SIR KENNETH GRAHAME

"Take the Adventure, heed the call, now, ere the irrevocable moment passes! ‘Tis but a banging of the door behind you, a blithesome step forward, and you are out of the old life and into the new! Then some day, some day long hence, jog home here if you will, when the cup has been drained and the play has been played, and sit down by your quiet river with a store of goodly memories for company."

JIM HARRISON

"Barring love I'll take my life in large doses alone--rivers, forests, fish, grouse, mountains. Dogs."

WILLIAM WORDSWORTH

SAMUEL ADAMS

"It is a very great mistake to imagine that the object of loyalty is the authority and interest of one individual man, however dignified by the applause or enriched by the success of popular actions."

TAO TE CHING, Lao Tzu

MARCUS AURELIUS

"Is your cucumber bitter? Throw it away. Are there briars in your path? Turn aside. That is enough. Do not go on and say, 'Why were things of this sort ever brought into this world?' neither intolerable nor everlasting - if thou bearest in mind that it has its limits, and if thou addest nothing to it in imagination. Pain is either an evil to the body (then let the body say what it thinks of it!)-or to the soul. But it is in the power of the soul to maintain its own serenity and tranquility."

VINCENT van GOGH

"What am I in the eyes of most people? A nonentity or an oddity or a disagreeable person — someone who has and will have no position in society, in short a little lower than the lowest. Very well — assuming that everything is indeed like that, then through my work I’d like to show what there is in the heart of such an oddity, such a nobody. This is my ambition, which is based less on resentment than on love in spite of everything, based more on a feeling of serenity than on passion. Even though I’m often in a mess, inside me there’s still a calm, pure harmony and music. In the poorest little house, in the filthiest corner, I see paintings or drawings. And my mind turns in that direction as if with an irresistible urge. As time passes, other things are increasingly excluded, and the more they are the faster my eyes see the picturesque. Art demands persistent work, work in spite of everything, and unceasing observation."

RICK LEACH (1975-1978)

RICHARD ADAMS

"One cloud feels lonely."

WINSLOW HOMER

The Lone Boat, North Woods Club, Adirondacks, 1892

THOMAS BABINGTON MACAULEY

And how can man die better / Than facing fearful odds / For the ashes of his fathers / And the temples of his gods

WATERHOUSE, BOREAS, 1903

WHITE HORSES Far out at sea / There are horses to ride, / Little white horses / That race with the tide. / Their tossing manes / Are the white sea-foam, / And the lashing winds / Are driving them home- / To shadowy stables / Fast they must flee, / To the great green caverns / Down under the sea. Irene Pawsey

UMBERTO LIMONGIELLO

F. SCOTT FITZGERALD

"I don't want to repeat my innocence. I want the pleasure of losing it again.” This Side of Paradise

RALPH WALDO EMERSON

"In skating over thin ice, our safety is in our speed."

ROBERT PLANT

GARY SNYDER

"There are those who love to get dirty and fix things. They drink coffee at dawn, beer after work. And those who stay clean, just appreciate things. At breakfast they have milk and juice at night. There are those who do both, they drink tea.”

IMMANUEL KANT

"Enlightenment is man's emergence from his self-imposed nonage. Nonage is the inability to use one's own understanding without another's guidance. This nonage is self-imposed if its cause lies not in lack of understanding but in indecision and lack of courage to use one's own mind without another's guidance. Dare to know! Sapere aude. 'Have the courage to use your own understanding,' is therefore the motto of the enlightenment."

DAN CAMPBELL

"We’re gonna kick you in the teeth, and when you punch us back we’re gonna smile at you, and when you knock us down we’re going to get up, and on the way, we’re going to bite a kneecap off. We’re going to stand up, and it’s going to take two more shots to knock us down. And on the way up, we’re going to take your other kneecap, and we’re going to get up, and it’s gonna take three shots to get us down. And when we do, we’re gonna take another hunk out of you."

THOMAS HUXLEY