Manutius, Erasmi Roterodami Adagiorum Chiliades tres, ac centuriae

fere totidem, 1508

‘How many books do you have?’ asked Meggie. She had grown up

among piles of books, but even she couldn’t imagine there were books behind all

the windows of this huge house.

Elinor inspected her again, this time with unconcealed

contempt. ‘How many?’ she repeated. ‘Do you think I count them like buttons or

peas? A very, very great many. There are probably more books in every single

room of this house than you will ever read – and some of them are so valuable

that I wouldn’t hesitate to shoot you if you dared touch them. But as you’re a

clever girl, or so your father assures me, you wouldn’t do that anyway, would

you?’

Meggie didn’t reply. Instead, she imagined standing on tiptoe

and spitting three times into this old witch’s face.

However, Mo just laughed. ‘You haven’t changed, Elinor,’ he

remarked. ‘A tongue as sharp as a paper-knife. But I warn you, if you harm

Meggie I’ll do the same to your beloved books.’

Elinor’s lips curled in a tiny smile. ‘Well said,’ she

answered, stepping aside. ‘You obviously haven’t changed either. Come in. I’ll

show you the books that need your help, and a few others as well.’

Meggie had always thought Mo had a lot of books. She never

thought so again, not after setting foot in Elinor’s house.

There were no haphazard piles lying around as they did at

home. Every book obviously had its place. But where other people have

wallpaper, pictures, or just an empty wall, Elinor had bookshelves. The shelves

were white and went right up to the ceiling in the entrance hall through which

she had first led them, but in the next room and the corridor beyond it the

shelves were as black as the tiles on the floor.

‘These books,’ announced Elinor with a dismissive gesture as

they passed the closely-ranked spines, ‘have accumulated over the years.

They’re not particularly valuable, mostly of mediocre quality, nothing out of

the ordinary. Should certain fingers be unable to control themselves and take

one off the shelf now and then,’ she added, casting a brief glance at Meggie,

‘I don’t suppose the consequences would be too serious. Just so long as once

those fingers have satisfied their curiosity they put every book back in its

right place again and don’t leave any unappetising bookmarks inside.’ Here,

Elinor turned to Mo. ‘Believe it or not,’ she said, ‘I actually found a

dried-up slice of salami used as a bookmark in one of the last books I bought,

a wonderful nineteenth-century first edition.’

Meggie couldn’t help giggling, which naturally earned her

another stern look. ‘It’s nothing to laugh about, young lady,’ said Elinor.

‘Some of the most wonderful books ever printed were lost because some fool of a

fishmonger tore out their pages to wrap his stinking fish. In the Middle Ages,

thousands of books were destroyed when people cut up their bindings to make

soles for shoes or to heat steam baths with their paper.’ The thought of such

incredible abominations, even if they had occurred centuries ago, made Elinor

gasp for air. ‘Well, let’s forget about that,’ she said, ‘or I shall get

overexcited. My blood pressure’s much too high as it is.’

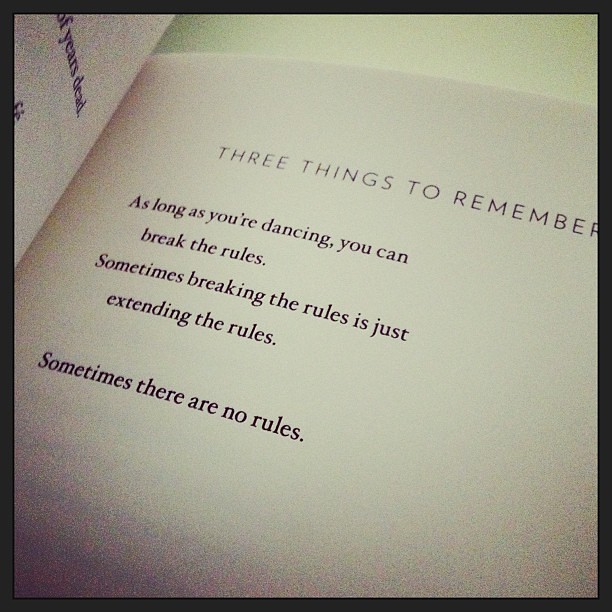

She had stopped in front of a door which had an anchor with

a dolphin coiled around it painted on the white wood. ‘This is a famous printer’s

special sign,’ explained Elinor, stroking the dolphin’s pointed nose with one

finger. ‘Just the thing for a library door, eh?’

‘I know,’ said Meggie. ‘Aldus Manutius. He lived in Venice

and printed books the right size to fit into his customers’ saddlebags.’

‘Really?’ Elinor wrinkled her brow, intrigued. ‘I didn’t

know that. In any case, I am the fortunate owner of a book that he printed with

his own hands in the year 1503.’

‘You mean it’s from his workshop,’ Meggie corrected her.

‘Of course that’s what I mean.’ Elinor cleared her throat

and gave Mo a reproachful glance, as if it could only be his fault that his

daughter was precocious enough to know such things. Then she put her hand on

the door handle. ‘No child,’ she said, as she pressed the handle down with

almost solemn reverence, ‘has ever before passed through this door, but as I

assume your father has taught you a certain respect for books I’ll make an

exception today. However, only on condition you keep at least three paces away

from the shelves. Is that agreed?’

For a moment Meggie felt like saying no, it wasn’t. She

would have loved to surprise Elinor by showing contempt for her precious books,

but she couldn’t do it. Her curiosity was too much for her. She felt almost as

if she could hear the books whispering on the other side of the half-open door.

They were promising her a thousand unknown stories, a thousand doors into

worlds she had never seen before. The temptation was stronger than Meggie’s

pride.

‘Agreed,’ she murmured, clasping her hands behind her back.

‘Three paces.’ Her fingers were itching with desire.

.jpg)