31 December 2025

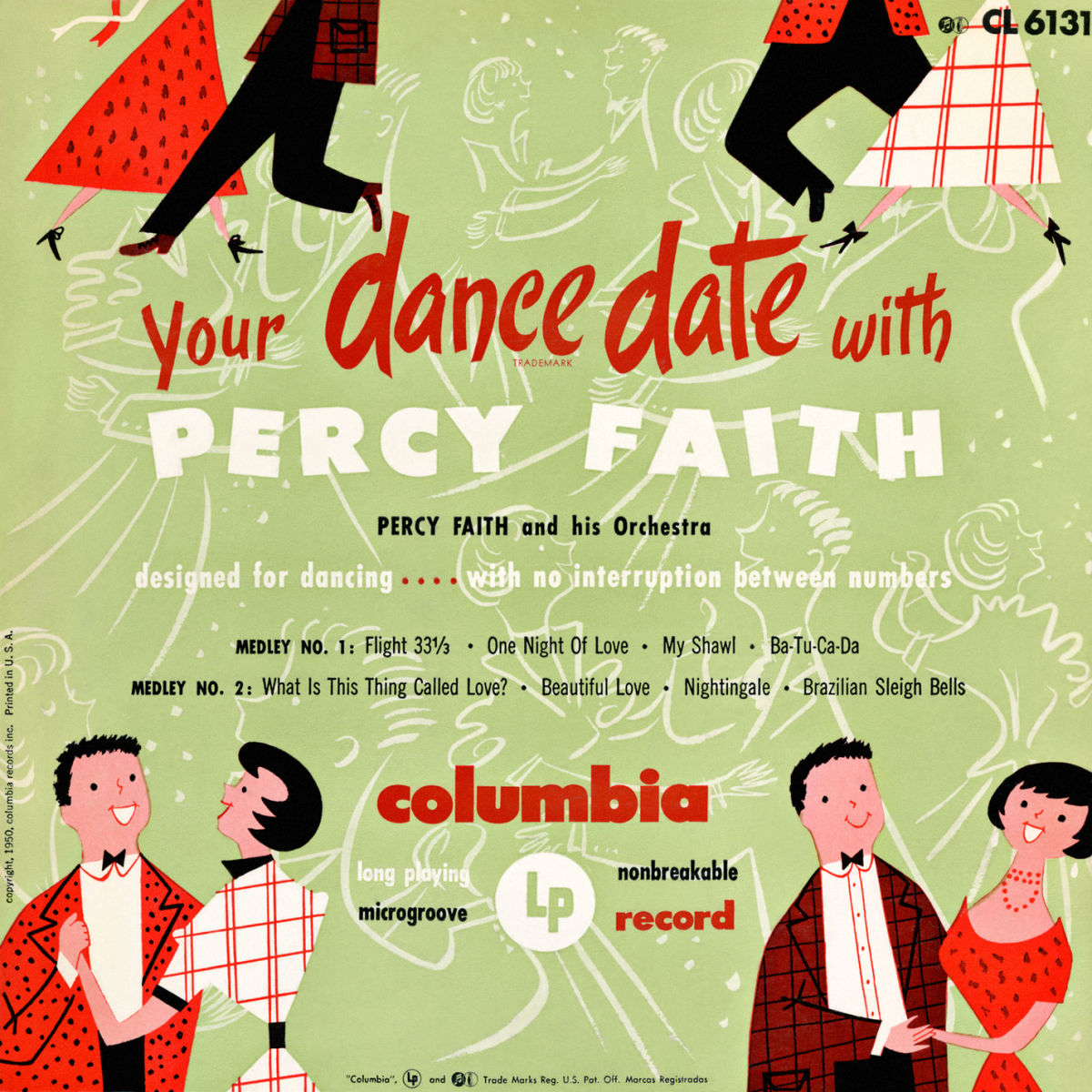

Long-Playing.

Another Amateur Night is upon us. Stay in and pile thirteen hours of long-playing, microgrooved, nonbreakable stereophonic platters on the hi-fi ...

Designed for dancing with no interruption between numbers.

Kurt suggests a worthy addition ...

Departing.

Delano, Milwaukee Road's Hiawatha Passenger Train Departing Union Station in Chicago, 1943

John Doe & The Sadies ....

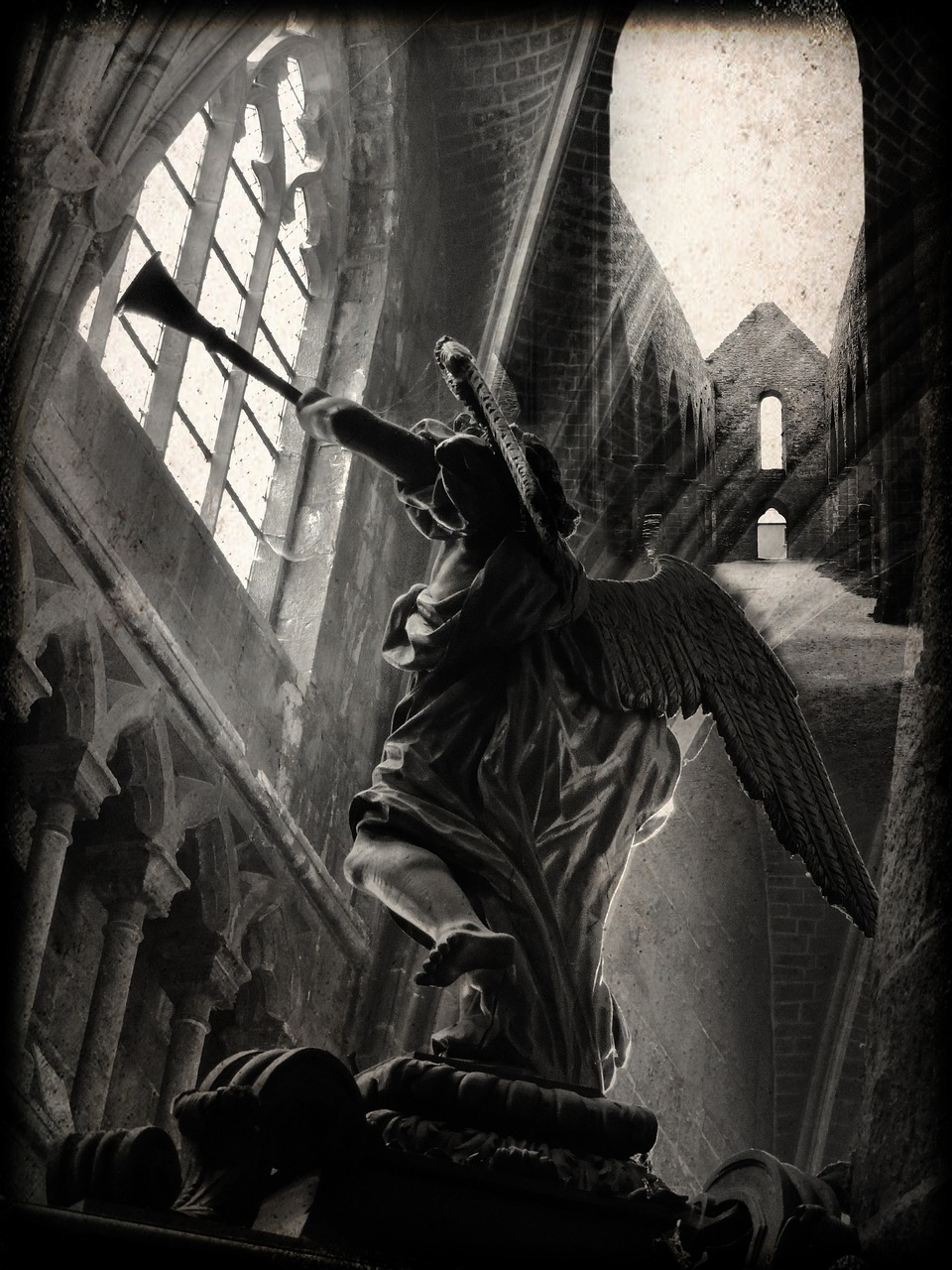

Ring.

IN MEMORIUM

Ring out, wild bells, to the wild sky,

The flying cloud, the frosty light:

The year is dying in the night;

Ring out, wild bells, and let him die.

Ring out the old, ring in the new,

Ring, happy bells, across the snow:

The year is going, let him go;

Ring out the false, ring in the true.

Ring out the grief that saps the mind

For those that here we see no more;

Ring out the feud of rich and poor,

Ring in redress to all mankind.

Ring out a slowly dying cause,

And ancient forms of party strife;

Ring in the nobler modes of life,

With sweeter manners, purer laws.

Ring out the want, the care, the sin,

The faithless coldness of the times;

Ring out, ring out my mournful rhymes

But ring the fuller minstrel in.

Ring out false pride in place and blood,

The civic slander and the spite;

Ring in the love of truth and right,

Ring in the common love of good.

Ring out old shapes of foul disease;

Ring out the narrowing lust of gold;

Ring out the thousand wars of old,

Ring in the thousand years of peace.

Ring in the valiant man and free,

The larger heart, the kindlier hand;

Ring out the darkness of the land,

Ring in the Christ that is to be.

Alfred, Lord Tennyson

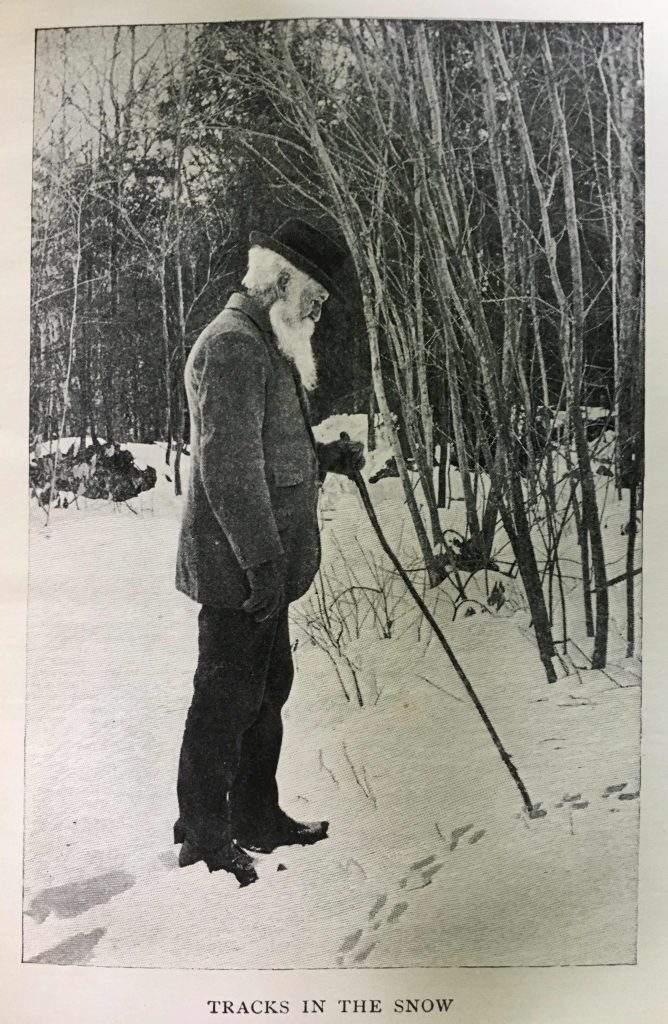

Nearer.

Shishkin, In the Wild North, 1891

AT the END of the YEAR -- BLESSINGS

As this year draws to its end,

We give thanks for the gifts it brought

And how they became inlaid within

Where neither time nor tide can touch them.

The days when the veil lifted

And the soul could see delight;

When a quiver caressed the heart

In the sheer exuberance of being here.

Surprises that came awake

In forgotten corners of old fields

Where expectation seemed to have quenched.

The slow, brooding times

When all was awkward

And the wave in the mind

Pierced every sore with salt.

The darkened days that stopped

The confidence of the dawn.

Days when beloved faces shone brighter

With light from beyond themselves;

And from the granite of some secret sorrow

A stream of buried tears loosened.

We bless this year for all we learned,

For all we loved and lost

And for the quiet way it brought us

Nearer to our invisible destination.

John O’Donohue

Thanks, Ors.

Labels:

appreciation,

art,

New Year,

ors,

poetry,

poetry rules!,

Shishkin

Sibelius, Symphony No. 5 in E-Flat Major, Op. 82

Karina Canellakis conducts the London Symphony Orchestra in a performance of the Allegro molto ...

30 December 2025

Strauss II, Wine, Women, and Song Waltz, Op. 333

Zubin Mehta and the Vienna Philharmonic perform ...

Values.

After OpenAI cofounder Greg Brockman's 2023 TED Talk, the head of TED, Chris Anderson, pushed him on the potential risks of insufficient feedback used to develop the patterns used in artificial intelligence's training ...

Anderson: Why isn't there just a huge risk of something truly terrible emerging?

Brockman: Well, I think all of these are questions of degree and scale and timing. And I think one thing people miss, too, is sort of the integration with the world is also this incredibly emergent, sort of, very powerful thing too. And so that's one of the reasons that we think it's so important to deploy incrementally.And so I think that what we kind of see right now, if you look at this talk, a lot of what I focus on is providing really high-quality feedback. Today, the tasks that we do, you can inspect them, right? It's very easy to look at that math problem and be like, "No, no, no, machine, seven was the correct answer." But even summarizing a book, like, that's a hard thing to supervise. Like, how do you know if this book summary is any good? You have to read the whole book. No one wants to do that. (nervous laughter, awkward silence)

The exact way the post-AGI world will look is hard to predict — that world will likely be more different from today's world than today's is from the 1500s. We do not yet know how hard it will be to make sure AGIs act according to the values of their operators.

Greg Brockman, from his testimony delivered to the U.S. House of Representatives in June 2018

Deliberately.

[I]t has become shorthand for content designed to elicit anger by being frustrating, offensive, or deliberately divisive in nature, and a mainstream term referenced in newsrooms across the world and discourse amongst content creators. It’s also a proven tactic to drive engagement, commonly seen in performative politics. As social media algorithms began to reward more provocative content, this has developed into practices such as rage-farming, which is a more consistently applied attempt to manipulate reactions and to build anger and engagement over time by seeding content with rage bait, particularly in the form of deliberate misinformation of conspiracy theory-based material.

Thank you, Jess, not only for recognizing my talent, but for keeping me abreast of essential current events.

If.

FRA LIPPO LIPPI

[Florentine painter, 1412-69]

I am poor brother Lippo, by your leave!

You need not clap your torches to my face.

Zooks, what's to blame? you think you see a monk!

What, 'tis past midnight, and you go the rounds,

And here you catch me at an alley's end

Where sportive ladies leave their doors ajar?

The Carmine's my cloister: hunt it up,

Do,—harry out, if you must show your zeal,

Whatever rat, there, haps on his wrong hole,

And nip each softling of a wee white mouse,

Weke, weke, that's crept to keep him company!

Aha, you know your betters! Then, you'll take

Your hand away that's fiddling on my throat,

And please to know me likewise. Who am I?

Why, one, sir, who is lodging with a friend

Three streets off—he's a certain . . . how d'ye call?

Master—a ...Cosimo of the Medici,

I' the house that caps the corner. Boh! you were best!

Remember and tell me, the day you're hanged,

How you affected such a gullet's-gripe!

But you, sir, it concerns you that your knaves

Pick up a manner nor discredit you:

Zooks, are we pilchards, that they sweep the streets

And count fair price what comes into their net?

He's Judas to a tittle, that man is!

Just such a face! Why, sir, you make amends.

Lord, I'm not angry! Bid your hang-dogs go

Drink out this quarter-florin to the health

Of the munificent House that harbours me

(And many more beside, lads! more beside!)

And all's come square again. I'd like his face—

His, elbowing on his comrade in the door

With the pike and lantern,—for the slave that holds

John Baptist's head a-dangle by the hair

With one hand ("Look you, now," as who should say)

And his weapon in the other, yet unwiped!

It's not your chance to have a bit of chalk,

A wood-coal or the like? or you should see!

Yes, I'm the painter, since you style me so.

What, brother Lippo's doings, up and down,

You know them and they take you? like enough!

I saw the proper twinkle in your eye—

'Tell you, I liked your looks at very first.

Let's sit and set things straight now, hip to haunch.

Here's spring come, and the nights one makes up bands

To roam the town and sing out carnival,

And I've been three weeks shut within my mew,

A-painting for the great man, saints and saints

And saints again. I could not paint all night—

Ouf! I leaned out of window for fresh air.

There came a hurry of feet and little feet,

A sweep of lute strings, laughs, and whifts of song, —

Flower o' the broom,

Take away love, and our earth is a tomb!

Flower o' the quince,

I let Lisa go, and what good in life since?

Flower o' the thyme—and so on. Round they went.

Scarce had they turned the corner when a titter

Like the skipping of rabbits by moonlight,—three slim shapes,

And a face that looked up . . . zooks, sir, flesh and blood,

That's all I'm made of! Into shreds it went,

Curtain and counterpane and coverlet,

All the bed-furniture—a dozen knots,

There was a ladder! Down I let myself,

Hands and feet, scrambling somehow, and so dropped,

And after them. I came up with the fun

Hard by Saint Laurence, hail fellow, well met,—

Flower o' the rose,

If I've been merry, what matter who knows?

And so as I was stealing back again

To get to bed and have a bit of sleep

Ere I rise up to-morrow and go work

On Jerome knocking at his poor old breast

With his great round stone to subdue the flesh,

You snap me of the sudden. Ah, I see!

Though your eye twinkles still, you shake your head—

Mine's shaved—a monk, you say—the sting 's in that!

If Master Cosimo announced himself,

Mum's the word naturally; but a monk!

Come, what am I a beast for? tell us, now!

I was a baby when my mother died

And father died and left me in the street.

I starved there, God knows how, a year or two

On fig-skins, melon-parings, rinds and shucks,

Refuse and rubbish. One fine frosty day,

My stomach being empty as your hat,

The wind doubled me up and down I went.

Old Aunt Lapaccia trussed me with one hand,

(Its fellow was a stinger as I knew)

And so along the wall, over the bridge,

By the straight cut to the convent. Six words there,

While I stood munching my first bread that month:

"So, boy, you're minded," quoth the good fat father

Wiping his own mouth, 'twas refection-time,—

"To quit this very miserable world?

Will you renounce" . . . "the mouthful of bread?" thought I;

By no means! Brief, they made a monk of me;

I did renounce the world, its pride and greed,

Palace, farm, villa, shop, and banking-house,

Trash, such as these poor devils of Medici

Have given their hearts to—all at eight years old.

Well, sir, I found in time, you may be sure,

'Twas not for nothing—the good bellyful,

The warm serge and the rope that goes all round,

And day-long blessed idleness beside!

"Let's see what the urchin's fit for"—that came next.

Not overmuch their way, I must confess.

Such a to-do! They tried me with their books:

Lord, they'd have taught me Latin in pure waste!

Flower o' the clove.

All the Latin I construe is, "amo" I love!

But, mind you, when a boy starves in the streets

Eight years together, as my fortune was,

Watching folk's faces to know who will fling

The bit of half-stripped grape-bunch he desires,

And who will curse or kick him for his pains,—

Which gentleman processional and fine,

Holding a candle to the Sacrament,

Will wink and let him lift a plate and catch

The droppings of the wax to sell again,

Or holla for the Eight and have him whipped,—

How say I?—nay, which dog bites, which lets drop

His bone from the heap of offal in the street,—

Why, soul and sense of him grow sharp alike,

He learns the look of things, and none the less

For admonition from the hunger-pinch.

I had a store of such remarks, be sure,

Which, after I found leisure, turned to use.

I drew men's faces on my copy-books,

Scrawled them within the antiphonary's marge,

Joined legs and arms to the long music-notes,

Found eyes and nose and chin for A's and B's,

And made a string of pictures of the world

Betwixt the ins and outs of verb and noun,

On the wall, the bench, the door. The monks looked black.

"Nay," quoth the Prior, "turn him out, d'ye say?

In no wise. Lose a crow and catch a lark.

What if at last we get our man of parts,

We Carmelites, like those Camaldolese

And Preaching Friars, to do our church up fine

And put the front on it that ought to be!"

And hereupon he bade me daub away.

Thank you! my head being crammed, the walls a blank,

Never was such prompt disemburdening.

First, every sort of monk, the black and white,

I drew them, fat and lean: then, folk at church,

From good old gossips waiting to confess

Their cribs of barrel-droppings, candle-ends,—

To the breathless fellow at the altar-foot,

Fresh from his murder, safe and sitting there

With the little children round him in a row

Of admiration, half for his beard and half

For that white anger of his victim's son

Shaking a fist at him with one fierce arm,

Signing himself with the other because of Christ

(Whose sad face on the cross sees only this

After the passion of a thousand years)

Till some poor girl, her apron o'er her head,

(Which the intense eyes looked through) came at eve

On tiptoe, said a word, dropped in a loaf,

Her pair of earrings and a bunch of flowers

(The brute took growling), prayed, and so was gone.

I painted all, then cried "'Tis ask and have;

Choose, for more's ready!"—laid the ladder flat,

And showed my covered bit of cloister-wall.

The monks closed in a circle and praised loud

Till checked, taught what to see and not to see,

Being simple bodies,—"That's the very man!

Look at the boy who stoops to pat the dog!

That woman's like the Prior's niece who comes

To care about his asthma: it's the life!''

But there my triumph's straw-fire flared and funked;

Their betters took their turn to see and say:

The Prior and the learned pulled a face

And stopped all that in no time. "How? what's here?

Quite from the mark of painting, bless us all!

Faces, arms, legs, and bodies like the true

As much as pea and pea! it's devil's-game!

Your business is not to catch men with show,

With homage to the perishable clay,

But lift them over it, ignore it all,

Make them forget there's such a thing as flesh.

Your business is to paint the souls of men—

Man's soul, and it's a fire, smoke . . . no, it's not . . .

It's vapour done up like a new-born babe—

(In that shape when you die it leaves your mouth)

It's . . . well, what matters talking, it's the soul!

Give us no more of body than shows soul!

Here's Giotto, with his Saint a-praising God,

That sets us praising—why not stop with him?

Why put all thoughts of praise out of our head

With wonder at lines, colours, and what not?

Paint the soul, never mind the legs and arms!

Rub all out, try at it a second time.

Oh, that white smallish female with the breasts,

She's just my niece . . . Herodias, I would say,—

Who went and danced and got men's heads cut off!

Have it all out!" Now, is this sense, I ask?

A fine way to paint soul, by painting body

So ill, the eye can't stop there, must go further

And can't fare worse! Thus, yellow does for white

When what you put for yellow's simply black,

And any sort of meaning looks intense

When all beside itself means and looks nought.

Why can't a painter lift each foot in turn,

Left foot and right foot, go a double step,

Make his flesh liker and his soul more like,

Both in their order? Take the prettiest face,

The Prior's niece . . . patron-saint—is it so pretty

You can't discover if it means hope, fear,

Sorrow or joy? won't beauty go with these?

Suppose I've made her eyes all right and blue,

Can't I take breath and try to add life's flash,

And then add soul and heighten them three-fold?

Or say there's beauty with no soul at all—

(I never saw it—put the case the same—)

If you get simple beauty and nought else,

You get about the best thing God invents:

That's somewhat: and you'll find the soul you have missed,

Within yourself, when you return him thanks.

"Rub all out!" Well, well, there's my life, in short,

And so the thing has gone on ever since.

I'm grown a man no doubt, I've broken bounds:

You should not take a fellow eight years old

And make him swear to never kiss the girls.

I'm my own master, paint now as I please—

Having a friend, you see, in the Corner-house!

Lord, it's fast holding by the rings in front—

Those great rings serve more purposes than just

To plant a flag in, or tie up a horse!

And yet the old schooling sticks, the old grave eyes

Are peeping o'er my shoulder as I work,

The heads shake still—"It's art's decline, my son!

You're not of the true painters, great and old;

Brother Angelico's the man, you'll find;

Brother Lorenzo stands his single peer:

Fag on at flesh, you'll never make the third!"

Flower o' the pine,

You keep your mistr ... manners, and I'll stick to mine!

I'm not the third, then: bless us, they must know!

Don't you think they're the likeliest to know,

They with their Latin? So, I swallow my rage,

Clench my teeth, suck my lips in tight, and paint

To please them—sometimes do and sometimes don't;

For, doing most, there's pretty sure to come

A turn, some warm eve finds me at my saints—

A laugh, a cry, the business of the world—

(Flower o' the peach

Death for us all, and his own life for each!)

And my whole soul revolves, the cup runs over,

The world and life's too big to pass for a dream,

And I do these wild things in sheer despite,

And play the fooleries you catch me at,

In pure rage! The old mill-horse, out at grass

After hard years, throws up his stiff heels so,

Although the miller does not preach to him

The only good of grass is to make chaff.

What would men have? Do they like grass or no—

May they or mayn't they? all I want's the thing

Settled for ever one way. As it is,

You tell too many lies and hurt yourself:

You don't like what you only like too much,

You do like what, if given you at your word,

You find abundantly detestable.

For me, I think I speak as I was taught;

I always see the garden and God there

A-making man's wife: and, my lesson learned,

The value and significance of flesh,

I can't unlearn ten minutes afterwards.

You understand me: I'm a beast, I know.

But see, now—why, I see as certainly

As that the morning-star's about to shine,

What will hap some day. We've a youngster here

Comes to our convent, studies what I do,

Slouches and stares and lets no atom drop:

His name is Guidi—he'll not mind the monks—

They call him Hulking Tom, he lets them talk—

He picks my practice up—he'll paint apace.

I hope so—though I never live so long,

I know what's sure to follow. You be judge!

You speak no Latin more than I, belike;

However, you're my man, you've seen the world

—The beauty and the wonder and the power,

The shapes of things, their colours, lights and shades,

Changes, surprises,—and God made it all!

—For what? Do you feel thankful, ay or no,

For this fair town's face, yonder river's line,

The mountain round it and the sky above,

Much more the figures of man, woman, child,

These are the frame to? What's it all about?

To be passed over, despised? or dwelt upon,

Wondered at? oh, this last of course!—you say.

But why not do as well as say,—paint these

Just as they are, careless what comes of it?

God's works—paint any one, and count it crime

To let a truth slip. Don't object, "His works

Are here already; nature is complete:

Suppose you reproduce her—(which you can't)

There's no advantage! you must beat her, then."

For, don't you mark? we're made so that we love

First when we see them painted, things we have passed

Perhaps a hundred times nor cared to see;

And so they are better, painted—better to us,

Which is the same thing. Art was given for that;

God uses us to help each other so,

Lending our minds out. Have you noticed, now,

Your cullion's hanging face? A bit of chalk,

And trust me but you should, though! How much more,

If I drew higher things with the same truth!

That were to take the Prior's pulpit-place,

Interpret God to all of you! Oh, oh,

It makes me mad to see what men shall do

And we in our graves! This world's no blot for us,

Nor blank; it means intensely, and means good:

To find its meaning is my meat and drink.

"Ay, but you don't so instigate to prayer!"

Strikes in the Prior: "when your meaning's plain

It does not say to folk—remember matins,

Or, mind you fast next Friday!" Why, for this

What need of art at all? A skull and bones,

Two bits of stick nailed crosswise, or, what's best,

A bell to chime the hour with, does as well.

I painted a Saint Laurence six months since

At Prato, splashed the fresco in fine style:

"How looks my painting, now the scaffold's down?"

I ask a brother: "Hugely," he returns—

"Already not one phiz of your three slaves

Who turn the Deacon off his toasted side,

But's scratched and prodded to our heart's content,

The pious people have so eased their own

With coming to say prayers there in a rage:

We get on fast to see the bricks beneath.

Expect another job this time next year,

For pity and religion grow i' the crowd—

Your painting serves its purpose!" Hang the fools!

—That is—you'll not mistake an idle word

Spoke in a huff by a poor monk, God wot,

Tasting the air this spicy night which turns

The unaccustomed head like Chianti wine!

Oh, the church knows! don't misreport me, now!

It's natural a poor monk out of bounds

Should have his apt word to excuse himself:

And hearken how I plot to make amends.

I have bethought me: I shall paint a piece

... There's for you! Give me six months, then go, see

Something in Sant' Ambrogio's! Bless the nuns!

They want a cast o' my office. I shall paint

God in the midst, Madonna and her babe,

Ringed by a bowery, flowery angel-brood,

Lilies and vestments and white faces, sweet

As puff on puff of grated orris-root

When ladies crowd to Church at midsummer.

And then i' the front, of course a saint or two—

Saint John' because he saves the Florentines,

Saint Ambrose, who puts down in black and white

The convent's friends and gives them a long day,

And Job, I must have him there past mistake,

The man of Uz (and Us without the z,

Painters who need his patience). Well, all these

Secured at their devotion, up shall come

Out of a corner when you least expect,

As one by a dark stair into a great light,

Music and talking, who but Lippo! I!—

Mazed, motionless, and moonstruck—I'm the man!

Back I shrink—what is this I see and hear?

I, caught up with my monk's-things by mistake,

My old serge gown and rope that goes all round,

I, in this presence, this pure company!

Where's a hole, where's a corner for escape?

Then steps a sweet angelic slip of a thing

Forward, puts out a soft palm—"Not so fast!"

—Addresses the celestial presence, "nay—

He made you and devised you, after all,

Though he's none of you! Could Saint John there draw—

His camel-hair make up a painting brush?

We come to brother Lippo for all that,

Iste perfecit opus! So, all smile—

I shuffle sideways with my blushing face

Under the cover of a hundred wings

Thrown like a spread of kirtles when you're gay

And play hot cockles, all the doors being shut,

Till, wholly unexpected, in there pops

The hothead husband! Thus I scuttle off

To some safe bench behind, not letting go

The palm of her, the little lily thing

That spoke the good word for me in the nick,

Like the Prior's niece . . . Saint Lucy, I would say.

And so all's saved for me, and for the church

A pretty picture gained. Go, six months hence!

Your hand, sir, and good-bye: no lights, no lights!

The street's hushed, and I know my own way back,

Don't fear me! There's the grey beginning. Zooks!

Robert Browning

Labels:

appreciation,

art,

Browning,

Lippi,

poetry,

poetry rules!

Goosens, Oboe Concerto in One Movement, Op. 45

Grave Mercer performs, accompanied by Dearbhla Brosnan ...

Happy Birthday, Rudyard Kipling

Burne-Jones, 2nd Bt, Rudyard Kipling, 1899

A SMUGGLER'S SONG

If you wake at midnight, and hear a horse's feet,

Don't go drawing back the blind, or looking in the street,

Them that ask no questions isn't told a lie.

Watch the wall my darling while the Gentlemen go by.

Five and twenty ponies,

Trotting through the dark -

Brandy for the Parson, 'Baccy for the Clerk.

Laces for a lady; letters for a spy,

Watch the wall my darling while the Gentlemen go by!

Running round the woodlump if you chance to find

Little barrels, roped and tarred, all full of brandy-wine,

Don't you shout to come and look, nor use 'em for your play.

Put the brishwood back again - and they'll be gone next day !

If you see the stable-door setting open wide;

If you see a tired horse lying down inside;

If your mother mends a coat cut about and tore;

If the lining's wet and warm - don't you ask no more !

If you meet King George's men, dressed in blue and red,

You be careful what you say, and mindful what is said.

If they call you " pretty maid," and chuck you 'neath the chin,

Don't you tell where no one is, nor yet where no one's been !

Knocks and footsteps round the house - whistles after dark -

You've no call for running out till the house-dogs bark.

Trusty's here, and Pincher's here, and see how dumb they lie

They don't fret to follow when the Gentlemen go by !

'If You do as you've been told, 'likely there's a chance,

You'll be give a dainty doll, all the way from France,

With a cap of Valenciennes, and a velvet hood -

A present from the Gentlemen, along 'o being good !

Five and twenty ponies,

Trotting through the dark -

Brandy for the Parson, 'Baccy for the Clerk.

Them that asks no questions isn't told a lie -

Watch the wall my darling while the Gentlemen go by!

Rudyard Kipling, born on this day in 1865

29 December 2025

Jimmy Buffett, "I Want to Go Back to Cartagena"

Jose Victor Escorcia, accordion ...

It's sandwich time.

Not.

Mahler, Portrait of Ludwig von Beethoven, 1815

The barriers are not erected which can say to aspiring talents and industry, “Thus far and no farther.”

Ludwig van Beethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven

Usable.

David Bowie's advice to young artists ...

We tend to think our opinions are a lot more important than other people's in some way. Often we feel as though we have the key to something. I don't think that we do at all, I just think we dwell on it more. We tend to look at the world as some usable substance more than a non-artist would. For many people just getting through life is enough, that's a big enough task, let alone having to look at the world and the universe and say, "Now, if I had my way ..."

Unsophistications.

Wyeth, N.C., Self-Portrait, 1920

The sheep-like tendency of human society soon makes inroads on a child's unsophistications, and then popular education completes the dastardly work with its systematic formulas, and away goes the individual, hurtling through space into that hateful oblivion of mediocrity. We are pruned into stumps, one resembling another, without character or grace.

N. C. Wyeth

Hats matter.

Worthy.

Each second we live is a new and unique moment of the universe, a moment that will never be again, and what do we teach our children? We teach them that two and two make four, and that Paris is the capital of France. When will we also teach them what they are? We should say to each of them: Do you know what you are? You are a marvel. You are unique. In all the years that have passed, there has never been another child like you. Your legs, your arms, your clever fingers, the way you move. You may become a Shakespeare, a Michelangelo, a Beethoven. You have the capacity for anything. Yes, you are a marvel. And when you grow up, can you then harm another who is, like you, a marvel? You must work, we must all work, to make the world worthy of its children.

Pablo Casals

Undeviating.

Stuart, George Washington, The Athenaeum Portrait, 1796

George Washington possessed the gift of inspired simplicity, a clarity and purity of vision that never failed him. Whatever petty partisan disputes swirled around him, he kept his eyes fixed on the transcendent goals that motivated his quest. As sensitive to criticism as any other man, he never allowed personal attacks or threats to distract him, following an inner compass that charted the way ahead. For a quarter century, he had stuck to an undeviating path that led straight to the creation of an independent republic, the enactment of the constitution and the formation of the federal government. History records few examples of a leader who so earnestly wanted to do the right thing, not just for himself but for his country. Avoiding moral shortcuts, he consistently upheld such high ethical standards that he seemed larger than any other figure on the political scene. Again and again, the American people had entrusted him with power, secure in the knowledge that he would exercise it fairly and ably and surrender it when his term of office was up. He had shown that the president and commander-in-chief of a republic could possess a grandeur surpassing that of all the crowned heads of Europe. He brought maturity, sobriety, judgement and integrity to a political experiment that could easily have grown giddy with its own vaunted success and he avoided the back biting envy and intrigue that detracted from the achievements of other founders. He had indeed been the indispensable man of the American Revolution.

Ron Chernow, from Washington: A Life

Off.

Have you ever thought

That snow grows old?

It falls

Young, dancing, light,

Fresh, innocent, white,

Peering in windows,

Perched on the sills,

Off again, flown again,

Driven of wind at its will...

Blown here and there...

Frivolous, fair.

It falls

More and more

Serious, old,

More and more...

Hard and cold...

Flakes fall and stay,

Weep and dance not,

Pile higher and higher,

Howl and shriek in the gale...

A shaft of sun — a smile...

A cloud of rain — tears...

Softer, weak,

Unresisting, gray,

Kinder now, but very old,

Flows stiffly down the hill

And off to sea.

Have you ever thought

That snow grows old?

Jeanne Goodstein

Wonder.

We all have a thirst for wonder. It's a deeply human quality. Science and religion are both bound up with it. What I'm saying is, you don't have to make stories up, you don't have to exaggerate. There's wonder and awe enough in the real world. Nature's a lot better at inventing wonders than we are.

Carl Sagan, from Contact

Happy Birthday, Pablo Casals

My work is my life. I cannot think of one without the other. To “retire” means to me to begin to die. The man who works and is never bored is never old. Work and interest in worthwhile things are the best remedy for age. Each day I am reborn. Each day I must begin again.

For the past eighty years I have started each day in the same manner. It is not a mechanical routine but something essential to my daily life. I go to the piano, and I play two preludes and fugues of Bach. I cannot think of doing otherwise. It is a sort of benediction on the house. But that is not its only meaning for me. It is a rediscovery of the world of which I have the joy of being a part. It fills me with awareness of the wonder of life, with a feeling of the incredible marvel of being a human being. The music is never the same for me, never. Each day is something new, fantastic, unbelievable.

Pablo Casals, born on this day in 1876

The Bourrées from Bach's Cello Suite No. 3, BWV 1009 ...

Wagner, The Ring Cycle

Richard Farnes, Music Director of Opera North from 2004-2016, conducts the entirety of Wagner's epic, Der Ring des Nibelungen ...

28 December 2025

Strauss II, Rejoice in Life Waltz, Op. 340

Andris Nelson conducts the New York Concert Orchestra ...

Transformation.

A priest once quoted to me the Roman saying that a religion is dead when the priests laugh at each other across the altar. I always laugh at the altar, be it Christian, Hindu, or Buddhist, because real religion is the transformation of anxiety into laughter.

Alan Watts

Responsible.

Ultimately, man should not ask what the meaning of his life is, but rather he must recognize that it is he who is asked. In a word, each man is questioned by life; and he can only answer to life by answering for his own life; to life he can only respond by being responsible.

Viktor E. Frankl, from Man's Search for Meaning

Immensity.

When we recognize our place in an immensity of light‐years and in the passage of ages, when we grasp the intricacy, beauty, and subtlety of life, then that soaring feeling, that sense of elation and humility combined, is surely spiritual -- so are our emotions in the presence of great art or music or literature.

Carl Sagan, from The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark

Simple.

What a wild winter sound,— wild and weird, up among the ghostly hills. I get up in the middle of the night to hear it. It is refreshing to the ear, and one delights to know that such wild creatures are among us. At this season Nature makes the most of every throb of life that can withstand her severity. This simplicity of winter has a deep moral. The return of Nature, after such a career of splendor and prodigality, to habits so simple and austere, is not lost either upon the head or the heart. It is the philosopher coming back from the banquet and the wine to a cup of water and a crust of bread.

John Burroughs, from "The Snow-Walkers"

One.

Yesterday, when weary with writing, I was called to supper, and a salad I had asked for was set before me. "It seems then," I said, "if pewter dishes, leaves of lettuce, grains of salt, drops of water, vinegar, oil and slices of eggs had been flying about in the air for all eternity, it might at last happen by chance that there would come a salad."

Johannes Kepler, from De Stella Nova

27 December 2025

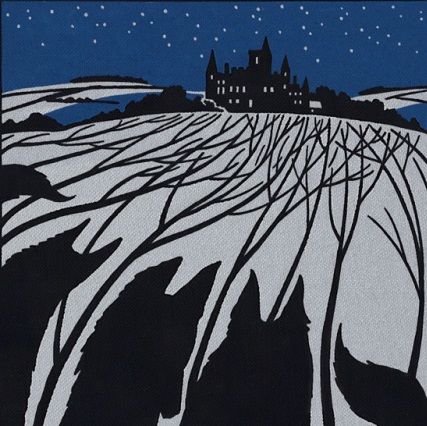

Dusk.

It was dusk - winter dusk. Snow lay white and shining over the pleated hills, and icicles hung from the forest trees. Snow lay piled on the dark road across Willoughby Wold, but from dawn men had been clearing it with brooms and shovels. There were hundreds of them at work, wrapped in sacking because of the bitter cold, and keeping together in groups for fear of the wolves, grown savage and reckless from hunger.

Joan Aiken, from The Wolves of Willoughby Chase

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

_%D0%9D%D0%B0_%D1%81%D0%B5%D0%B2%D0%B5%D1%80%D0%B5_%D0%B4%D0%B8%D0%BA%D0%BE%D0%BC.jpg)

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)