Suddenly, black was everywhere. It caked the flesh of miners

and ironworkers; it streaked the walls and windows of industrial towns; it

thickened the smoky air above. Proprietors donned black clothing to indicate

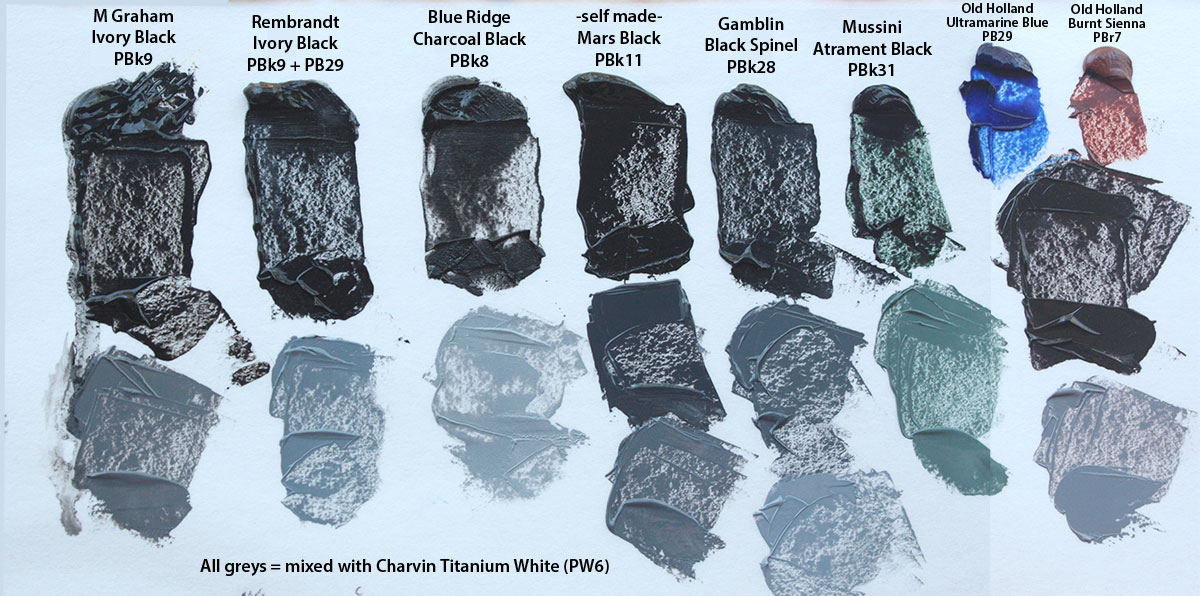

their status and respectability. New black dyes and pigments created in

factories and chemical laboratories entered painters’ studios, enabling a new

expression for the new themes of the industrial age: factory work and revolt,

technology and warfare, urbanity and pollution, and a rejection of the old

status quo. A new class of citizen, later to be dubbed the “proletariat,” began

to appear in illustrations under darkened smokestacks. The industrial

revolution had found its color.

Black is technically an absence: the visual experience of a lack of light. A perfect black dye absorbs all of the light that impinges on it, leaving nothing behind. This ideal is remarkably difficult to manufacture. The industrialization of the 18th and 19th centuries made it easier, providing chemists and paint-makers with a growing palette of black—and altering the subjects that the color would come to represent. “These things are intimately connected,” says science writer Philip Ball, author of Bright Earth: The Invention of Color. The reinvention of black, in other words, went far beyond the color.

Black is technically an absence: the visual experience of a lack of light. A perfect black dye absorbs all of the light that impinges on it, leaving nothing behind. This ideal is remarkably difficult to manufacture. The industrialization of the 18th and 19th centuries made it easier, providing chemists and paint-makers with a growing palette of black—and altering the subjects that the color would come to represent. “These things are intimately connected,” says science writer Philip Ball, author of Bright Earth: The Invention of Color. The reinvention of black, in other words, went far beyond the color.

No comments:

Post a Comment