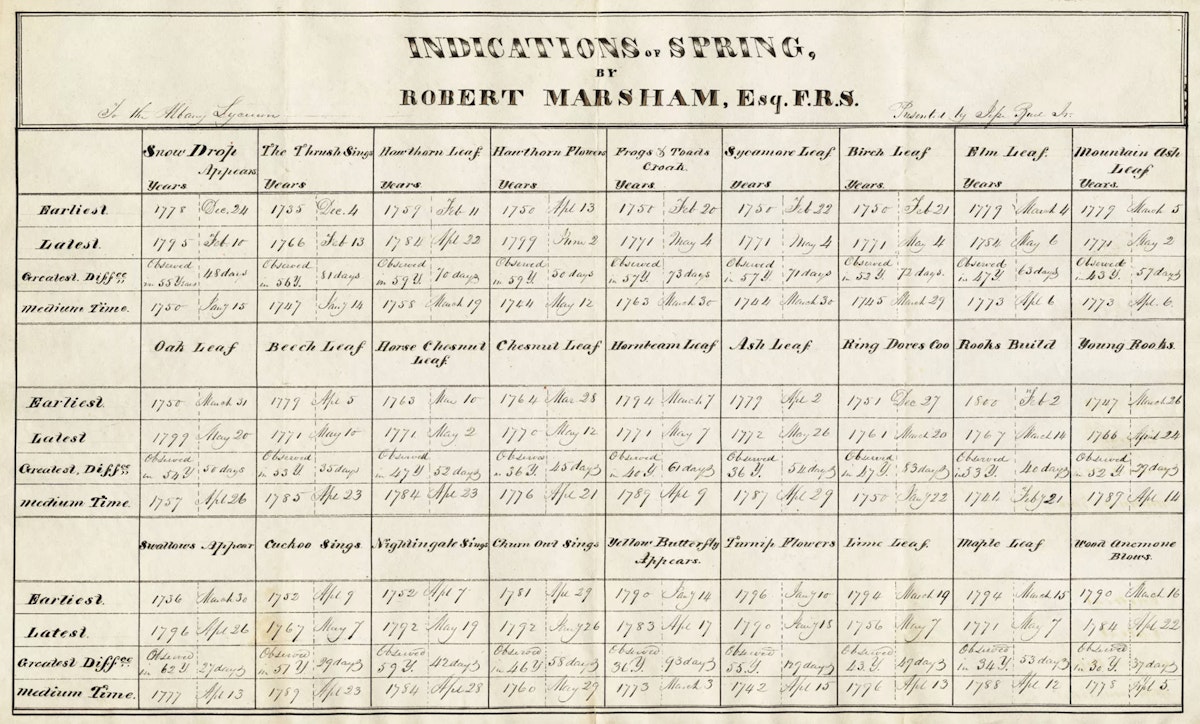

Hugh Aldersey-Williams explores the lifelong calendrical project of Robert Marsham and asks, "What can we learn from observing the progression of spring — a hawthorn’s first flowering, the return of birdsong on a particular day?"

Noticing signs of spring is not confined to the scientifically minded, of course. It is an idea with a long provenance. Buddhist monks in Japan were recording the arrival of the cherry blossom as far back as the ninth century. Some of Marsham’s “data points” (such as the swallow and the cuckoo) have long held a place in popular lore and folk songs. The old English saying “Ne’er cast a clout till May be out” — a warning not to remove outer clothes too soon in the year — is usually supposed to refer to the month of May. But English May weather is highly variable, and it is more likely that the saying refers to the May tree, or hawthorn, which generally flowers at some point during that month (long after it has come into leaf). Whether it does so early or late is determined chiefly by the weather conditions, making it a more reliable index for an appropriate choice of dress than a calendar date.Robert Marsham’s project was handed down in the family and only came to a halt in 1958 when his great-great-great-granddaughter Mary died and her descendants were advised that their amateur contribution was no longer required, presumably judged to be no match for modern scientific methods. Despite its abrupt termination, it is the unbroken long run — 222 years — of Marsham’s “Indications of Spring” that gives it lasting scientific worth. There are a few patchy early records for places in the UK, but Marsham’s is the first truly systematic dataset, according to Tim Sparks, a professor of zoology and quantitative biology at the universities of Cambridge, Liverpool, and Poznań. “It is the longest such record for the UK and has been of immense value in determining the variability in spring and in its response to prevailing weather conditions. He inspired many others to do likewise.” Marsham’s record stretches back far enough that it can serve as a baseline for the investigation of changes that have already happened in the more recent past as well as for ongoing studies of the present situation.One merit of Marsham’s idea is surely that it is so easily grasped. You do not need to be a scientist to understand his results — or to begin recording your own data. In the mid-nineteenth century, the observation of seasonal changes in nature acquired its own name — phenology — as the gentleman scientists of the Victorian age began to add their contributions. Today, Marsham’s pioneering work inspires successor projects around the world, many of them examples of “citizen science”, relying on the participation of members of the public.

No comments:

Post a Comment