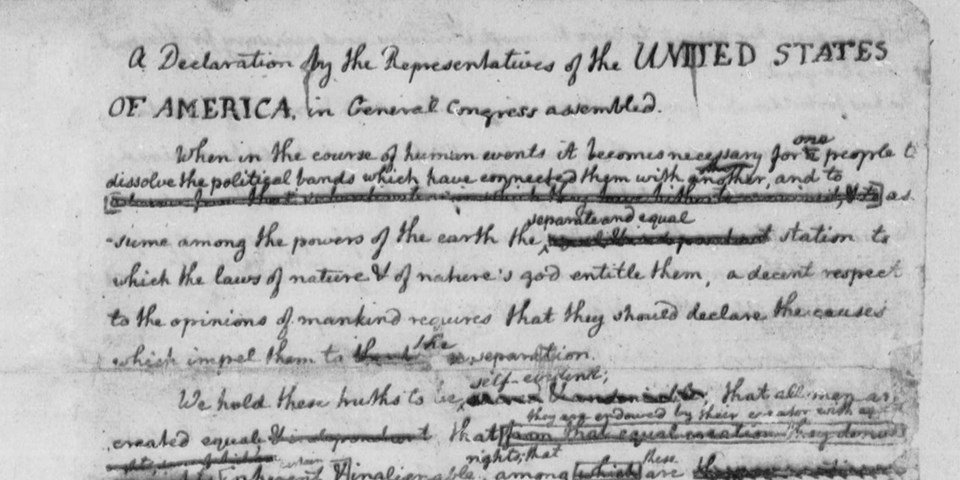

Alone in his upstairs parlor at Seventh and Market, Jefferson went to work, seated in an unusual revolving Windsor chair and holding on his lap a portable writing box, a small folding desk of his own design which, like the chair, he had especially made for him by a Philadelphia cabinetmaker. Traffic rattled by below the open windows. The June days and nights turned increasingly warm. He worked rapidly and, to judge by surviving drafts, with a sure command of his material. He had none of his books with him, nor needed any, he later claimed. It was not his objective to be original, he would explain, only “to place before mankind the common sense of the subject.”

The desk on which a new nation announced itself to the world in 1776—in Jefferson’s script of marvelous clarity and straight-line precision—had a long career of service. Indeed, Jefferson used it for almost 50 years, through all his subsequent life as politician, ambassador, statesman, inventor, architect, educator, President and private citizen. And as the United States grew and prospered with each passing year, the significance of the writing box grew too.

Read the rest here.

Three annotated texts of The Declaration of Independence are here.

No comments:

Post a Comment