The charm ... of what is classical, in art or literature, is that of the well-known tale, to which we can nevertheless listen over and over again, because it is told so well. To the absolute beauty of its artistic form is added the accidental, tranquil charm of familiarity. There are times, indeed, at which these charms fail to work on our spirits at all, because they fail to excite us. “Romanticism,” says Stendhal, “is the art of presenting to people the literary works which, in the actual state of their habits and beliefs, are capable of giving them the greatest possible pleasure; classicism, on the contrary, of presenting them with that which gave the greatest possible pleasure to their grandfathers.” But then, beneath all changes of habits and beliefs, our love of that mere abstract proportion—of music—which what is classical in literature possesses, still maintains itself in the best of us, and what pleased our grandparents may at least tranquilize us. The “classic” comes to us out of the cool and quiet of other times, as the measure of what a long experience has shown will at least never displease us. And in the classical literature of Greece and Rome, as in the classics of the last century, the essentially classical element is that quality of order in beauty, which they possess indeed in a pre-eminent degree, and which impresses some minds to the exclusion of everything else in them.

It is the addition of strangeness to beauty, that constitutes the romantic character in art; and the desire of beauty being a fixed element in every artistic organization, it is the addition of curiosity to this desire of beauty, that constitutes the romantic temper. Curiosity, and the desire of beauty, have each their place in art, as in all true criticism. When one’s curiosity is deficient, when one is not eager enough for new impressions and new pleasures, one is liable to value mere academical properties too highly, to be satisfied with worn-out or conventional types, with the insipid ornament of Racine, or the prettiness of that later Greek sculpture which passed so long for true Hellenic work; to miss those places where the handiwork of nature, or of the artist, has been most cunning; to find the most stimulating products of art a mere irritation.

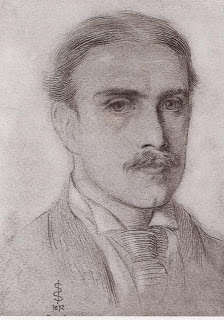

Walter Pater, from "The Classic and Romantic in Literature", born on this day in 1839

No comments:

Post a Comment