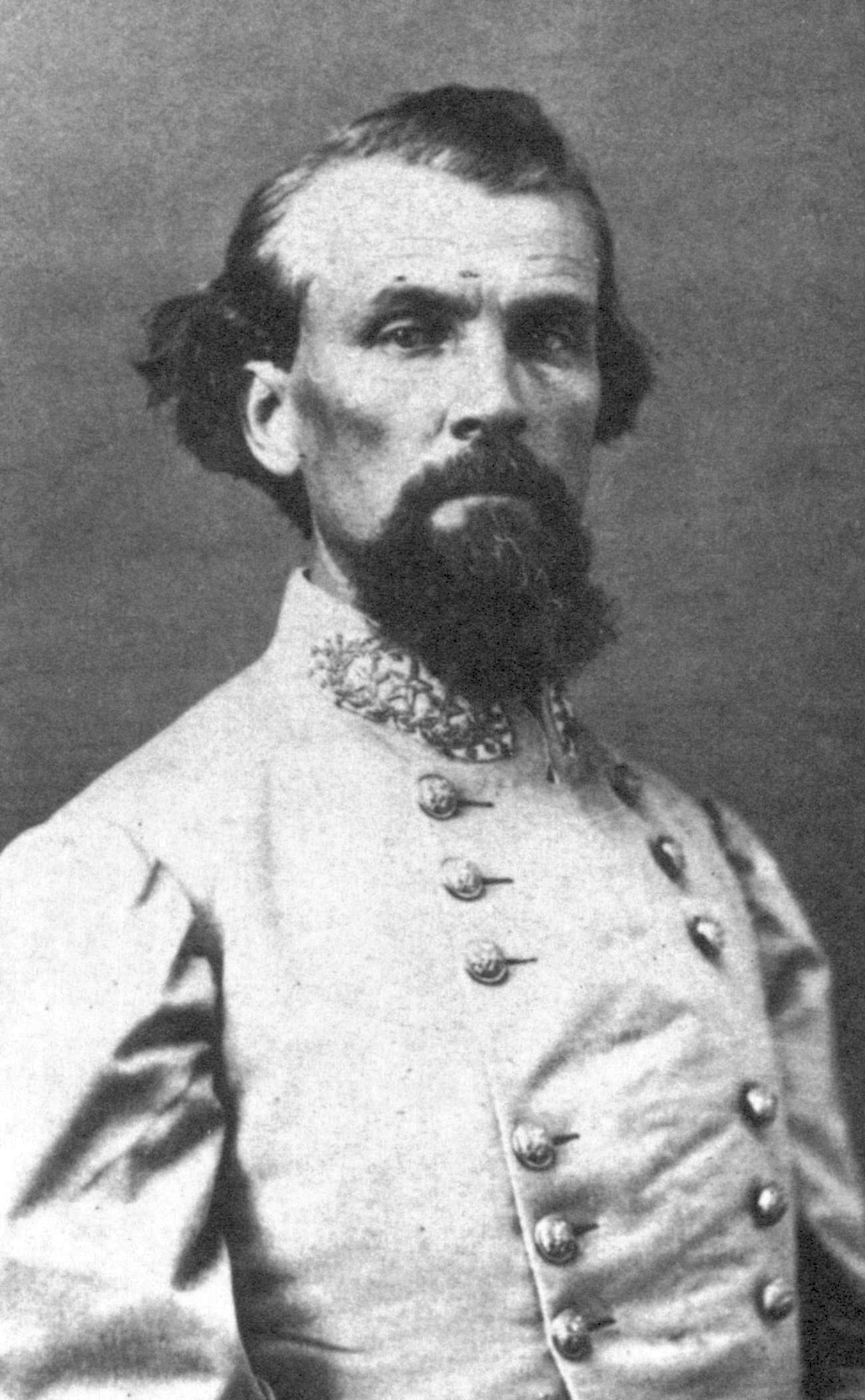

Nathan Bedford Forrest was born on this date in 1821.

These were no mere bushwhackers, like those who operated along the Kansas-Missouri border. From the beginning Forrest recognized the importance of discipline—an attribute learned in part from his own experiences as custodian of a fierce temper.

Forrest did not rise from frontier hayseed to millionaire plantation owner and businessman without learning self-control. In a hard-drinking age he was abstemious. He was neither hothead nor brawler. His outbursts were fewer than legend allows, usually brief and often followed by apologies. His wartime lapses in self-control were nonetheless spectacular—he brandished his sword at one fellow general during a blowup over regulations and reportedly drew a pistol on another who disputed his troopers’ right of way. In a time and place when one was expected to defend his honor personally and immediately, Forrest’s behavior did not put him beyond the pale, as it might have in the Army of Northern Virginia.

Even when conscription agents resorted to scraping the bottom of the Confederacy’s barrel, Forrest could always raise men. Enlisting as a private and soon commissioned a lieutenant colonel, he successively recruited a battalion, then a regiment and ultimately an entire corps. While convalescing from his injuries at Shiloh, Forrest ran a recruiting advertisement in the Memphis Daily Appeal with the stirring phrase, “Come on, boys, if you want a heap of fun and to kill some Yankees.”

While the training his men received was often marginal and occasionally nonexistent, Forrest compensated for it by his strict insistence on camp discipline. Leaves and passes were restricted. “Hoorahing”—the frontier practice of galloping about on horses and firing guns indiscriminately— was a court-martial offense. Forrest sentenced his own son and fellow transgressors to several hours of carrying fence rails on their shoulders for breaking camp discipline. In the field the commander strictly forbade straggling and looting.

The key to Forrest’s skill as a tactician was his innate ability to read a fight. He understood how best to balance mounted and dismounted action, defense and attack, commitment and pursuit. Whatever his issues of self-control behind the lines or in personal combat, Forrest never let emotion overcome him in conducting a battle.

His defining approach involved maintaining pressure, harassing enemy forces before an engagement, engaging them at all points during a fight and giving them no time to rally. “Whenever you see anything blue, shoot at it and do all you can to keep up the scare,” was his injunction during one skirmish.

He was born to be a soldier the way John Keats was born to be a poet.

Shelby Foote, from The Civil War ...

No comments:

Post a Comment