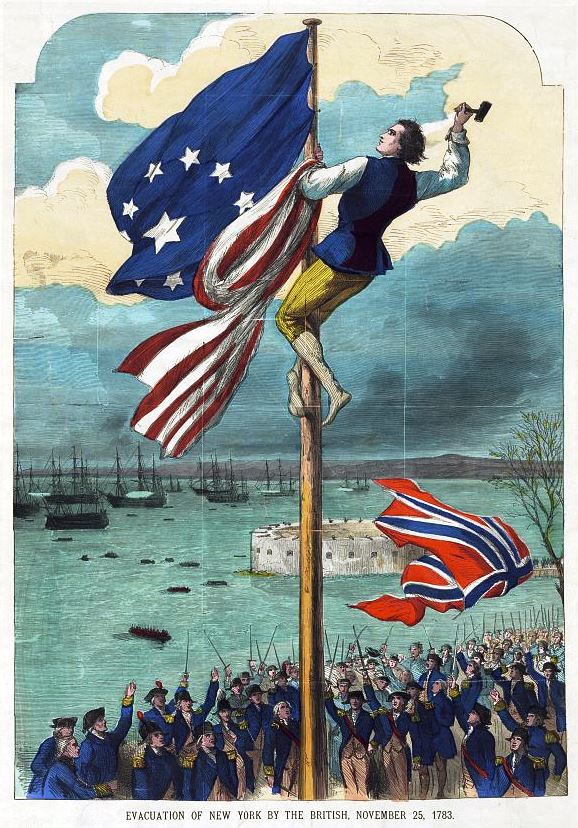

On this day in 1783, the British evacuated New York, their last military position in the United States, during the Revolutionary War.

On Wednesday, November 20, Washington rode down from West Point to Tarrytown where he, Gov. Clinton, and Lt. Gov. Van Cortlandt met and lodged at Edward Covenhaven’s tavern. Also that evening, former officers and soldiers were meeting at Cape’s Tavern in the city to plan for the procession of the governor, Washington, and the last 800 troops remaining in his service. They resolved to all wear a black-and-white Union Cockade as a Badge of Distinction representing Louis XVI, more for its ability to annoy the British soldiers than any abiding affection for their ally, the Catholic monarch of France. But come the twenty-second, Carleton had not yet completed his evacuation. Washington’s triumphant return to the city whose loss haunted him throughout the war would have to wait a few more days.On November 20, 1783, Washington, Clinton, and the army’s remaining soldiers marched from Tarrytown to Day’s Tavern in Harlem, one of the scenes of Washington’s retreat following the Battle of Long Island Carleton’s months-long evacuation would finally be completed on November 25, 1783. Immediately, citizens began preparing an entire day of festivities. Throughout the early hours of the morning, people streamed into the city. The final British troops were supposed to leave the island at noon, at which point Washington, Clinton, and their contingent would march into the city. Much attention was paid to timing to make sure that American forces arrived immediately upon the last evacuation so as not to leave any intermittent period in which there was no authority.Before noon, Major General Henry Knox led a column of soldiers–dragoons, artillery, and infantrymen–down from McGowan’s Pass in Harlem. As he reached the outer limits of the city, he paused to await final word from a British messenger. When word came, Knox and company marched into the city to Cape’s Tavern on Broadway. Once there, Knox led a group of mounted citizens–wearing their black-and-white Union cockades–back to Bull’s Head Tavern just outside the city on the Bowery to meet with Washington, Clinton, and the rest of the procession. Citizens had gathered there hoping to get a glimpse of men whose names and deeds they knew of largely from newspaper reports. The plan was that once the last British troops had left and the British flag had been brought down over Fort George, a blast of thirteen cannon shots would signal to Washington and Clinton that the procession into the city could begin, which would end with the raising of the American flag. There was, however, a hitch in the plan.

No comments:

Post a Comment