The Journal of the American Revolution provides accounts of the first reading of the Declaration of Independence ...

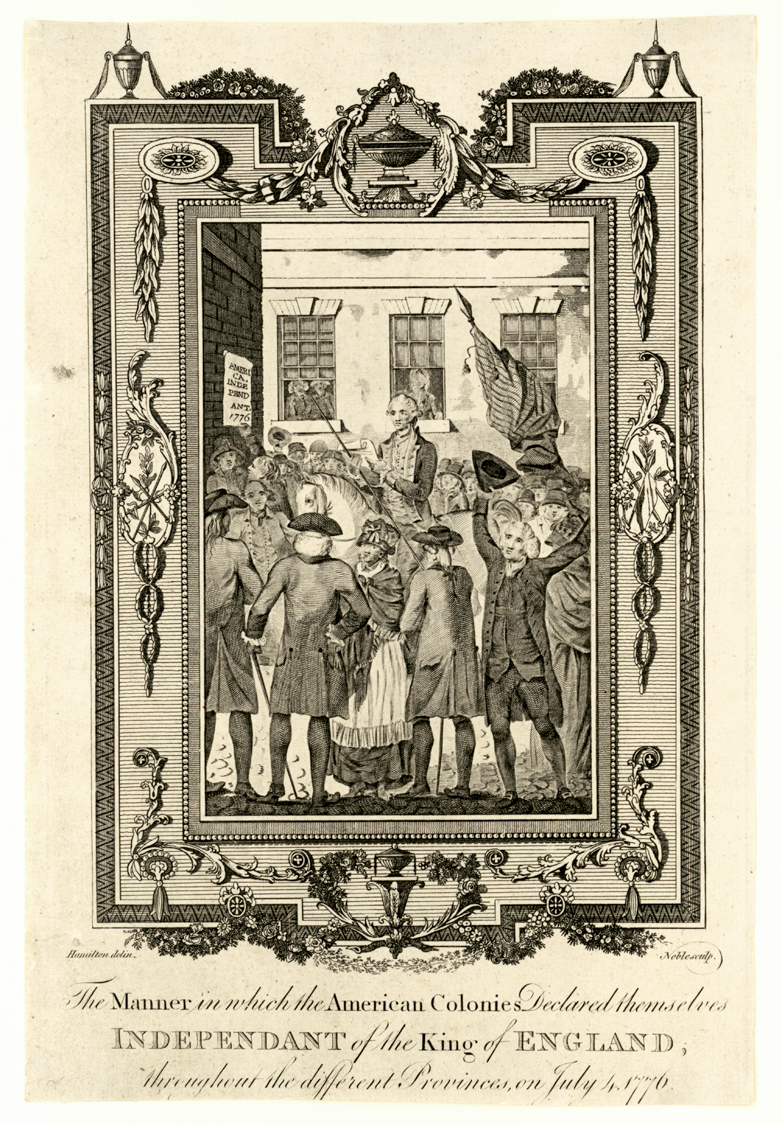

In 1878 Demorest’s Monthly Magazine published an article which said, “Timothy Matlack is probably entitled to especial commemoration and veneration as the actual reader of the Declaration of Independence, from the State House steps on July 4, 1776.” This witness who identified Matlack as the speaker was Anthony Morris, who was ten years old at the time. Morris was later a merchant and lawyer in Philadelphia, a Speaker of the Pennsylvania State Senate, and a minister to Spain for the United States. He gave his account later in life to the spouse of a Matlack descendant. He told her:Did you know that your husband’s great grandfather was the first one to read the Declaration of Independence to the people of Philadelphia from the State House steps? I was a young boy, July 4, 1776, at the time and stood in the crowd and heard him. Whether he was chosen as a reader for his stentorian voice or for the position he held in the Commonwealth I cannot tell. I only know that I heard him.A local historian named A. M. Stackhouse later asked, “May not the occasion referred to by Mr. Morris have been an unofficial reading by Colonel Matlack? He was at that time clerk of Congress. The last mention made of him in that capacity is on the 11th day of July 1776.” The testimony of Anthony Morris is the only one that names Matlack as the speaker.Another account identifies another witness, a militia man named George Piper. The author of a brief biography stated that “Piper listened to the reading of the Declaration of Independence in front of the State House, Philadelphia, July 4, 1776.”Although legal scholar Ritz was unaware of both the Morris and Piper testimonies, he pointed to the contemporaneous journal of Henry Melchior Muhlenberg. On July 2, 1776, Muhlenberg wrote: “It is said that the Continental Congress resolved to declare the thirteen united colonies free and independent.” On July 4, 1776, he wrote: “Today the Continental Congress openly declared the united provinces of North America to be free and independent states.” The change in emphasis from “resolved to declare” to “openly declared” suggests Muhlenberg witnessed or heard about the public reading(s).In her book American Scripture: Making of the Declaration of Independence, the historian Pauline Maier refers readers to Ritz “For evidence that the Declaration was first read publicly on July 4 to a small audience that included few ‘respectable’ people.” Regarding this characterization of the people gathered that day, both Biddle and Logan said they were members of the “lower” sector of society. In another diary entry Logan wrote derisively, “The crowd that assembled at the State House was not great and those among them who joined in the acclamation were not the most sober or reflecting.” This description helps us distinguish between the informal crowd of working artisans and laborers who heard the Declaration read on July 4, and the formal one of wealthier merchants and lawyers who attended the grand ceremony on July 8.The first people to hear the words of the Declaration were the common people standing out on Chestnut Street on July 4, 1776. The first to read them in public was likely either Timothy Matlack or Charles Thomson. As the people’s tribune, Matlack would have been addressing his constituents. If the historian Deborah Norris Logan is correct, the crowd followed the speaker to the Court House where he read the Declaration a second time.

No comments:

Post a Comment