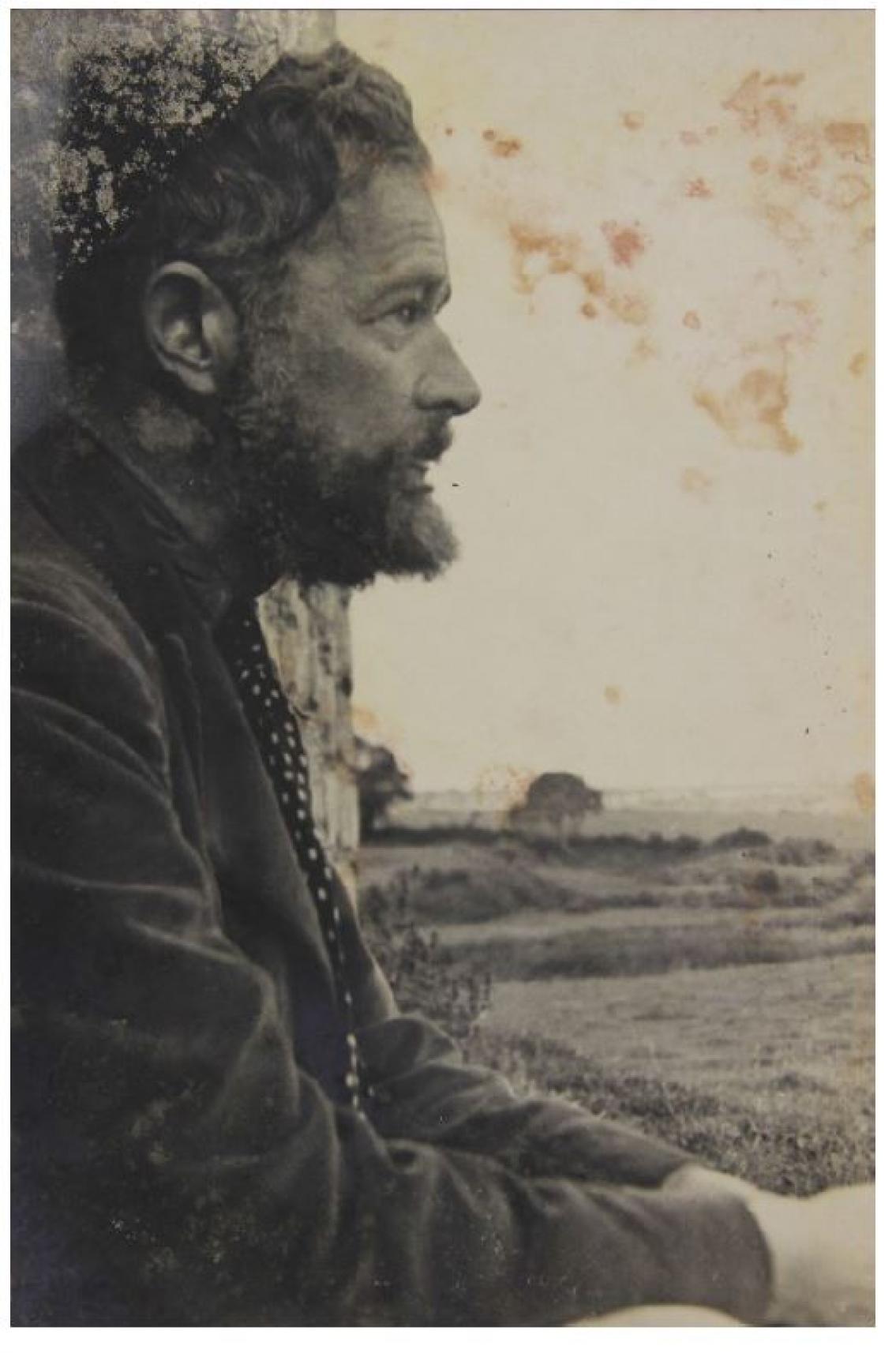

Described by biographer Sylvia Townsend Warner as "chased by a mad black wind," this "hermetic and sometimes cranky man" wrote more than twenty-five books. He was an illustrator and calligrapher. He translated medieval bestiaries. He painted, fished, raced airplanes, built furniture, sailed boats, plowed fields, and flew hawks at prey. Late in life, he made deep-sea dives in a heavy old suit with a bulbous helmet, which made him look like a Zuni mudhead.

New skills "aerated his intelligence," Warner tells us. For his 1955 translation of a 12th-century bestiary, he taught himself Latin. Through a character in one of his novels he hinted at himself. "The best thing for being sad," the character says, "is to learn something."

Much of White's knowledge of the natural world resurfaced in his teaching -- he was for many years a schoolmaster -- although greater experts in his subjects accused him of smattering. "But smatterer or no," writes Warner, White "held his pupils' attention; their imagination, too, calling out an unusual degree of solicitude -- as though in the tall, gowned figure these adolescents recognized a hidden adolescent, someone unhappy, fitful, self-dramatizing, and not knowing much about finches."

He wore scarlet. He was "nobly shabby." He drank, he said, "in order not to be sober." He kept owls and paid his students to trap mice to feed them. Fed, the owls perched on his shoulder as he sat under an apple tree, speaking to him in little squeals.

CONNECT

Thank You, Jess.

No comments:

Post a Comment