For a climber is as a man standing on the edge of an abyss. The chance of falling over or of the ground crumbling beneath his feet is negligible, yet his very closeness to the edge makes him think. He cannot but visualize what would happen if he stepped forward, and realizes with a shock of what very small significance it would be. The sun would still be shining, and the waterfall would still be roaring below. And suddenly he realizes, perhaps far the first ttme in his life, what a friendly fellow the sun is, what vividness there is in the green around him.

There is a kind of fear which is very closely akin to love, and this is the fear which the climber enjoys. It is, to use a contradictory term, a brave fear; a fear which announces its presence, perhaps very loudly, but raises no insuperable barrier to achievement. The climber enjoys being frightened, because he knows that fear is no impediment.

Lastly, we may ask ourselves whether the good effects resulting from climbing are permanent. From the pinnacle of our premature old age, we think we can say they are.

The immediate exaltation after a difficult climb only lasts two or three days at the outside, but there is a residual effect after the effervescence has died down. The imagination, through its violent and constant use in climbing, receives a permanent increase in strength. It becomes constructive instead of haphazard, so that instead of thinking what he might do a climber thinks more of what he could and may do. Each achievement makes the next one easier.

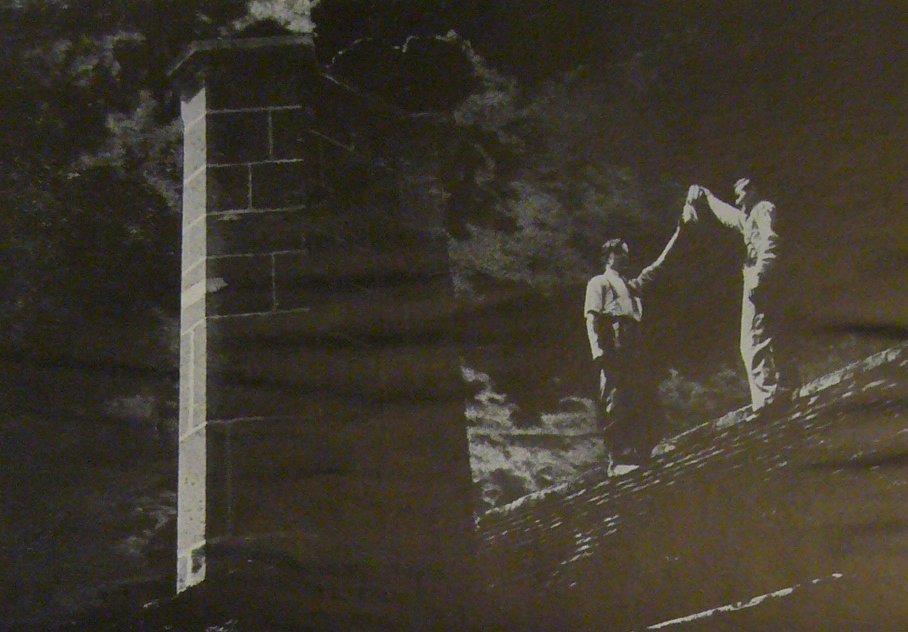

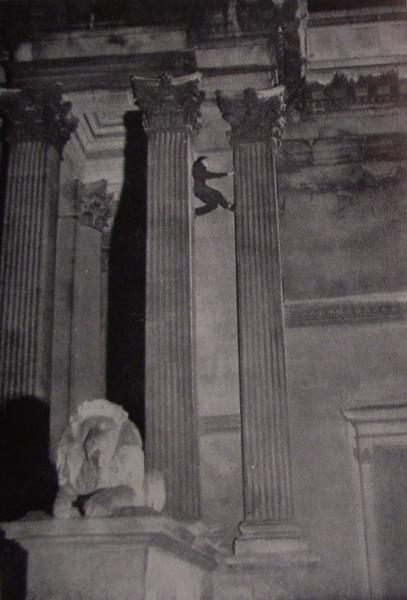

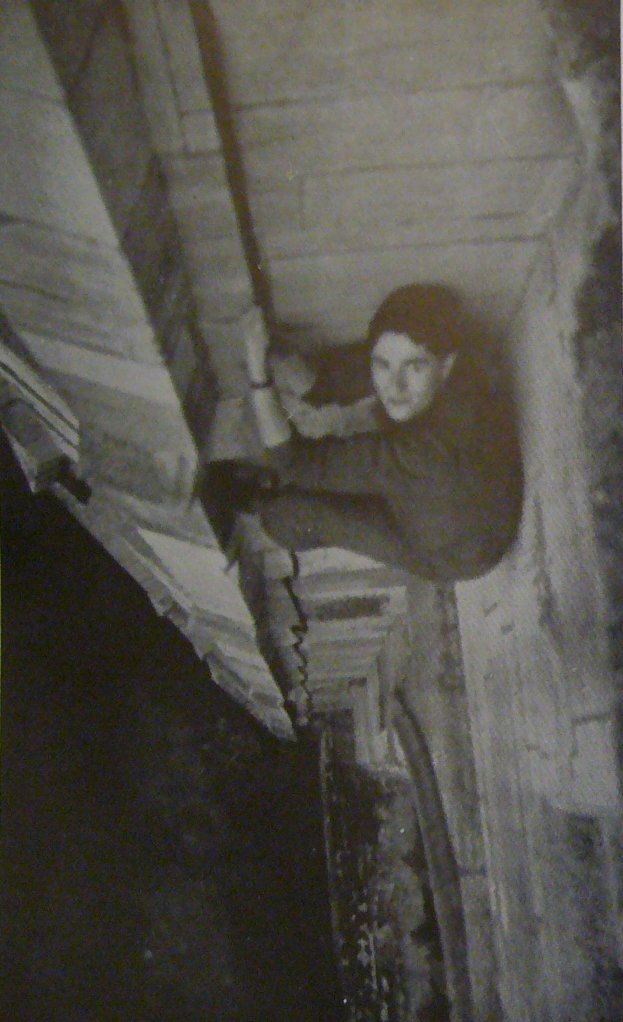

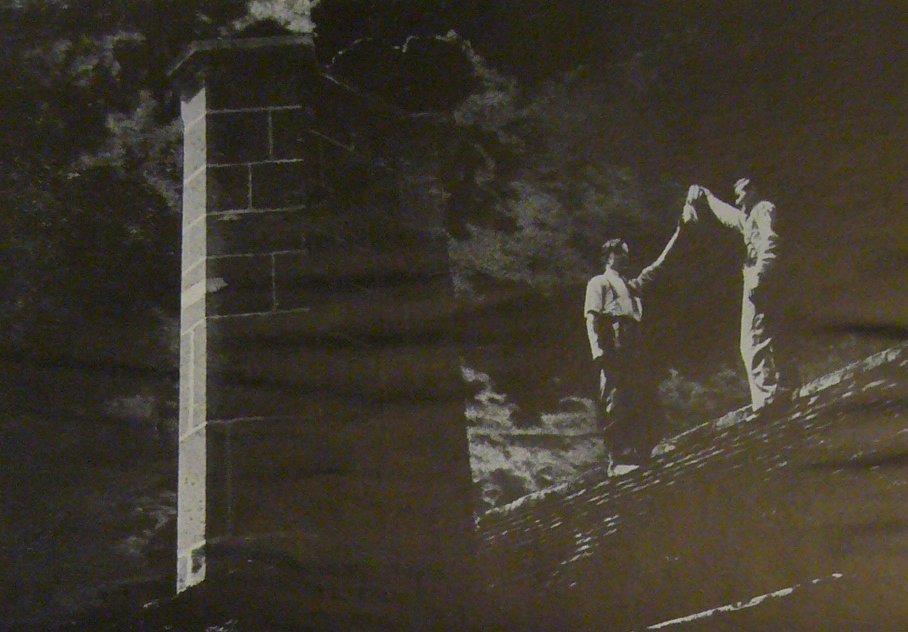

And so, sitting in our armchair by the fireside, we smile as our thoughts carry us back to Cambridge. It has been great fun. These last few weeks have been equal to the best of the old days in college, when to go out involved so little effort that we did so all too rarely. The trouble with the camera, the climbing, the excitement after each flash, the long car journey of over fifty miles up to Cambridge in the evening, night after night, and the return in the darkness before dawn, the hedgerows rushing past on the edge of vision, the feeling of control as the tyres gripped on each corner taken too fast, the moon shining her torch on a sleeping world, or the sense of the country around on a dark night; the memory of bad climbers forcing themselves to be brave on easy buildings, and good climbers arousing our admiration on the severe climbs; the feeling of knowing intimately all those with whom we have been out. Yes, it has been great fun.

Occasionally, as we pause in our reading to throw a log on the fire, we feel a vague unrest. It all seems too comfortable. The night is dark, and in its inscrutability tries to lead us on to action; or the moon laughs down, as though trying to tell us what she can see in other parts of the world. We stir in our chair, and wonder whether it is a sign of strength or weakness that makes us ignore the call. Cambridge is there, just over an hour from us, her roof-tops waiting.

No comments:

Post a Comment