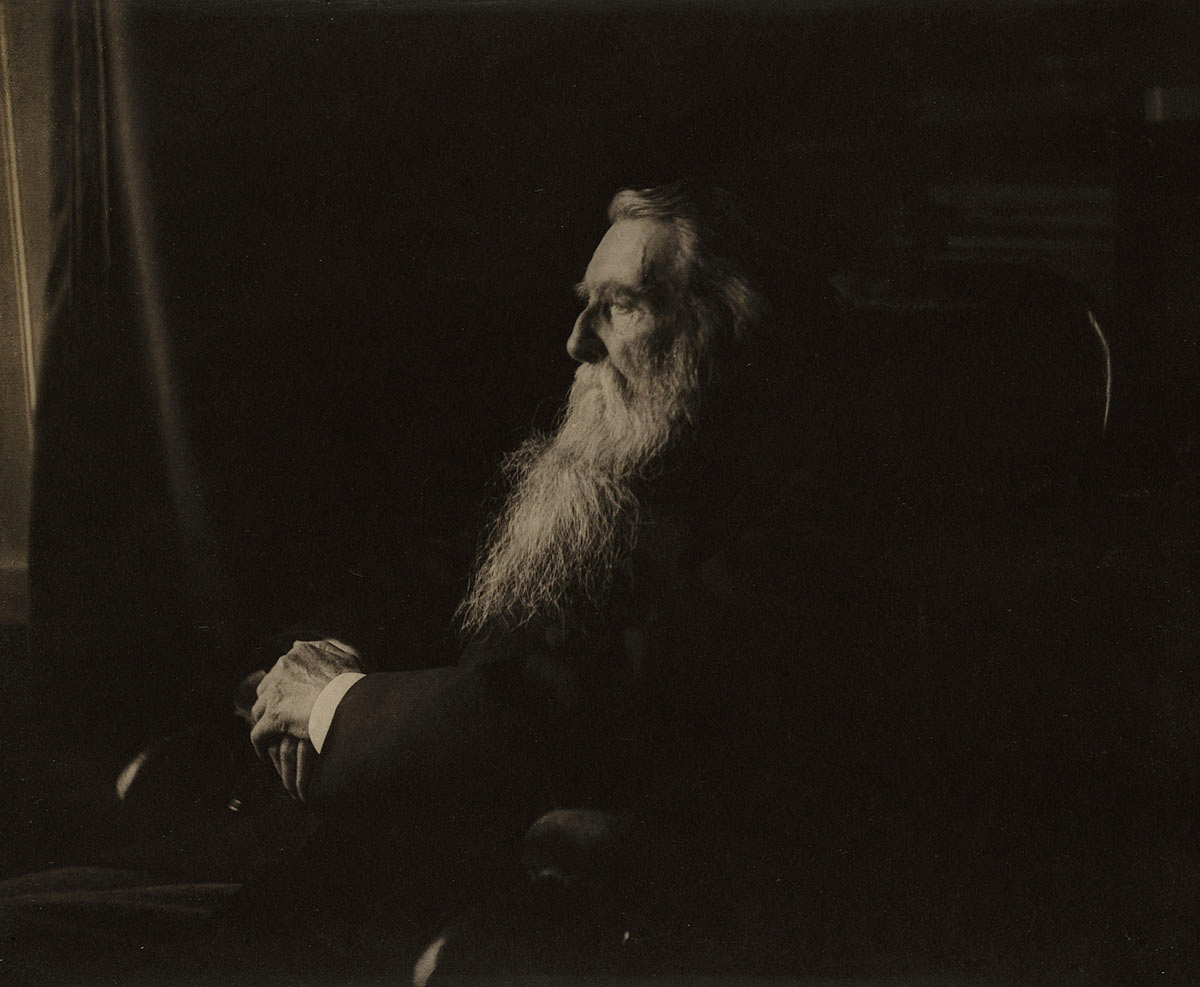

Hollyer, John Ruskin, 1871

Ruskin was a man of intense contradictions. Like a fish, he said, it is healthiest to swim against the stream. He described himself mostly as a Conservative, but many of his ideas were socialist in outlook. He believed in hierarchy but also that the rich had a responsibility to protect the poor. He had a privileged background but gave away much of his wealth, reflecting in his autobiography that “it was probably much happier to live in a small house, and have Warwick Castle to be astonished at, than to live in Warwick Castle and have nothing to be astonished at”.

Through his many books, Ruskin influenced the tastes of his generation, championing artists who were until then little known in England. While he was moved by Turner’s paintings, he was “utterly crushed to the earth” by the genius of the Venetian artist Tintoretto. Ruskin’s publications sparked fresh interest in Italian art and particularly Venetian Gothic architecture. He made numerous prints and drawings, fearing that, if he did not, Venice might vanish undocumented like “a lump of sugar in hot tea”.

Indeed, Ruskin was not only an astute critic but a talented artist in his own right. He likened the “strong instinct” he felt to draw to the instinct to eat and drink. Drawings of gooseberry blossom and ragwort, mountains and clouds, minerals and birds, including an exquisite sulphur-crested cockatoo he sketched at the zoo, line the walls of the London exhibition. Art, he believed, should reflect nature.

But what made Ruskin so unusual was that he was eager to pass his skills down not only to men like himself but to everyone. He was apparently as at ease teaching members of the Working Men’s College in London, where he was "wildly popular", as he was the students of Oxford, where he was elected Slade Professor of Fine Art in 1869. Hundreds turned out to his lectures, which he would deliver with fascinating props, such as model feathers 10 times their actual size.

No comments:

Post a Comment