Upon that night, when fairies light

On Cassilis Downans dance,

Or owre the lays, in splendid blaze,

On sprightly coursers prance;

Or for Colean the route is ta'en,

Beneath the moon's pale beams;

There, up the cove, to stray and rove,

Among the rocks and streams

To sport that night.

Among the bonny winding banks,

Where Doon rins, wimplin' clear,

Where Bruce ance ruled the martial ranks,

And shook his Carrick spear,

Some merry, friendly, country-folks,

Together did convene,

To burn their nits, and pou their stocks,

And haud their Halloween

Fu' blithe that night.

The lasses feat, and cleanly neat,

Mair braw than when they're fine;

Their faces blithe, fu' sweetly kythe,

Hearts leal, and warm, and kin';

The lads sae trig, wi' wooer-babs,

Weel knotted on their garten,

Some unco blate, and some wi' gabs,

Gar lasses' hearts gang startin'

Whiles fast at night.

Then, first and foremost, through the kail,

Their stocks maun a' be sought ance;

They steek their een, and graip and wale,

For muckle anes and straught anes.

Poor hav'rel Will fell aff the drift,

And wander'd through the bow-kail,

And pou't, for want o' better shift,

A runt was like a sow-tail,

Sae bow't that night.

Then, staught or crooked, yird or nane,

They roar and cry a' throu'ther;

The very wee things, todlin', rin,

Wi' stocks out owre their shouther;

And gif the custoc's sweet or sour.

Wi' joctelegs they taste them;

Syne cozily, aboon the door,

Wi cannie care, they've placed them

To lie that night.

The lasses staw frae 'mang them a'

To pou their stalks of corn:

But Rab slips out, and jinks about,

Behint the muckle thorn:

He grippet Nelly hard and fast;

Loud skirl'd a' the lasses;

But her tap-pickle maist was lost,

When kitlin' in the fause-house

Wi' him that night.

The auld guidwife's well-hoordit nits,

Are round and round divided,

And monie lads' and lasses' fates

Are there that night decided:

Some kindle coothie, side by side,

And burn thegither trimly;

Some start awa, wi' saucy pride,

And jump out-owre the chimlie

Fu' high that night.

Jean slips in twa wi' tentie ee;

Wha 'twas she wadna tell;

But this is Jock, and this is me,

She says in to hersel:

He bleezed owre her, and she owre him,

As they wad never mair part;

Till, fuff! he started up the lum,

And Jean had e'en a sair heart

To see't that night.

Poor Willie, wi' his bow-kail runt,

Was brunt wi' primsie Mallie;

And Mallie, nae doubt, took the drunt,

To be compared to Willie;

Mall's nit lap out wi' pridefu' fling,

And her ain fit it brunt it;

While Willie lap, and swore by jing,

'Twas just the way he wanted

To be that night.

Nell had the fause-house in her min',

She pits hersel and Rob in;

In loving bleeze they sweetly join,

Till white in ase they're sobbin';

Nell's heart was dancin' at the view,

She whisper'd Rob to leuk for't:

Rob, stowlins, prie'd her bonny mou',

Fu' cozie in the neuk for't,

Unseen that night.

But Merran sat behint their backs,

Her thoughts on Andrew Bell;

She lea'es them gashin' at their cracks,

And slips out by hersel:

She through the yard the nearest taks,

And to the kiln goes then,

And darklins graipit for the bauks,

And in the blue-clue throws then,

Right fear't that night.

And aye she win't, and aye she swat,

I wat she made nae jaukin',

Till something held within the pat,

Guid Lord! but she was quakin'!

But whether 'was the deil himsel,

Or whether 'twas a bauk-en',

Or whether it was Andrew Bell,

She didna wait on talkin'

To spier that night.

Wee Jennie to her grannie says,

"Will ye go wi' me, grannie?

I'll eat the apple at the glass

I gat frae Uncle Johnnie:"

She fuff't her pipe wi' sic a lunt,

In wrath she was sae vap'rin',

She notice't na, an aizle brunt

Her braw new worset apron

Out through that night.

"Ye little skelpie-limmer's face!

I daur you try sic sportin',

As seek the foul thief ony place,

For him to spae your fortune.

Nae doubt but ye may get a sight!

Great cause ye hae to fear it;

For mony a ane has gotten a fright,

And lived and died deleeret

On sic a night.

"Ae hairst afore the Sherramoor, --

I mind't as weel's yestreen,

I was a gilpey then, I'm sure

I wasna past fifteen;

The simmer had been cauld and wat,

And stuff was unco green;

And aye a rantin' kirn we gat,

And just on Halloween

It fell that night.

"Our stibble-rig was Rab M'Graen,

A clever sturdy fallow:

His son gat Eppie Sim wi' wean,

That lived in Achmacalla:

He gat hemp-seed, I mind it weel,

And he made unco light o't;

But mony a day was by himsel,

He was sae sairly frighted

That very night."

Then up gat fechtin' Jamie Fleck,

And he swore by his conscience,

That he could saw hemp-seed a peck;

For it was a' but nonsense.

The auld guidman raught down the pock,

And out a hanfu' gied him;

Syne bade him slip frae 'mang the folk,

Some time when nae ane see'd him,

And try't that night.

He marches through amang the stacks,

Though he was something sturtin;

The graip he for a harrow taks.

And haurls it at his curpin;

And every now and then he says,

"Hemp-seed, I saw thee,

And her that is to be my lass,

Come after me, and draw thee

As fast this night."

He whistled up Lord Lennox' march

To keep his courage cheery;

Although his hair began to arch,

He was say fley'd and eerie:

Till presently he hears a squeak,

And then a grane and gruntle;

He by his shouther gae a keek,

And tumbled wi' a wintle

Out-owre that night.

He roar'd a horrid murder-shout,

In dreadfu' desperation!

And young and auld came runnin' out

To hear the sad narration;

He swore 'twas hilchin Jean M'Craw,

Or crouchie Merran Humphie,

Till, stop! she trotted through them

And wha was it but grumphie

Asteer that night!

Meg fain wad to the barn hae gaen,

To win three wechts o' naething;

But for to meet the deil her lane,

She pat but little faith in:

She gies the herd a pickle nits,

And two red-cheekit apples,

To watch, while for the barn she sets,

In hopes to see Tam Kipples

That very nicht.

She turns the key wi cannie thraw,

And owre the threshold ventures;

But first on Sawnie gies a ca'

Syne bauldly in she enters:

A ratton rattled up the wa',

And she cried, Lord, preserve her!

And ran through midden-hole and a',

And pray'd wi' zeal and fervour,

Fu' fast that night;

They hoy't out Will wi' sair advice;

They hecht him some fine braw ane;

It chanced the stack he faddom'd thrice

Was timmer-propt for thrawin';

He taks a swirlie, auld moss-oak,

For some black grousome carlin;

And loot a winze, and drew a stroke,

Till skin in blypes cam haurlin'

Aff's nieves that night.

A wanton widow Leezie was,

As canty as a kittlin;

But, och! that night amang the shaws,

She got a fearfu' settlin'!

She through the whins, and by the cairn,

And owre the hill gaed scrievin,

Whare three lairds' lands met at a burn

To dip her left sark-sleeve in,

Was bent that night.

Whyles owre a linn the burnie plays,

As through the glen it wimpl't;

Whyles round a rocky scaur it strays;

Whyles in a wiel it dimpl't;

Whyles glitter'd to the nightly rays,

Wi' bickering, dancing dazzle;

Whyles cookit underneath the braes,

Below the spreading hazel,

Unseen that night.

Among the brackens, on the brae,

Between her and the moon,

The deil, or else an outler quey,

Gat up and gae a croon:

Poor Leezie's heart maist lap the hool!

Near lav'rock-height she jumpit;

but mist a fit, and in the pool

Out-owre the lugs she plumpit,

Wi' a plunge that night.

In order, on the clean hearth-stane,

The luggies three are ranged,

And every time great care is ta'en',

To see them duly changed:

Auld Uncle John, wha wedlock joys

Sin' Mar's year did desire,

Because he gat the toom dish thrice,

He heaved them on the fire

In wrath that night.

Wi' merry sangs, and friendly cracks,

I wat they didna weary;

And unco tales, and funny jokes,

Their sports were cheap and cheery;

Till butter'd so'ns, wi' fragrant lunt,

Set a' their gabs a-steerin';

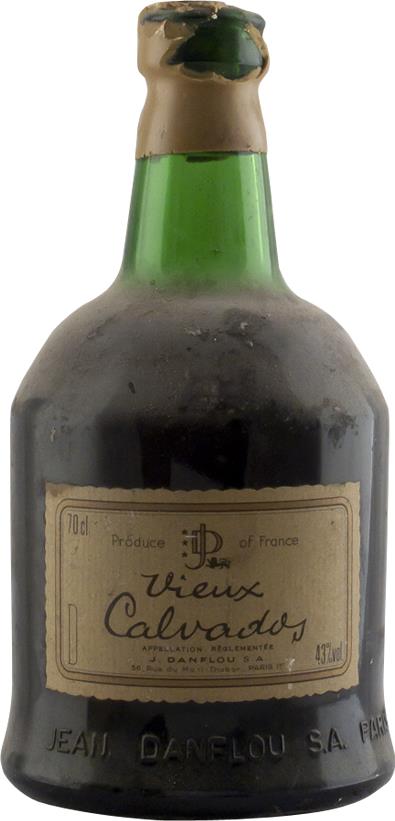

Syne, wi' a social glass o' strunt,

They parted aff careerin'

Fu' blythe that night.

Robert Burns