31 October 2020

Flickering.

Secret.

Wisdom.

Home.

Dancing.

Excellent.

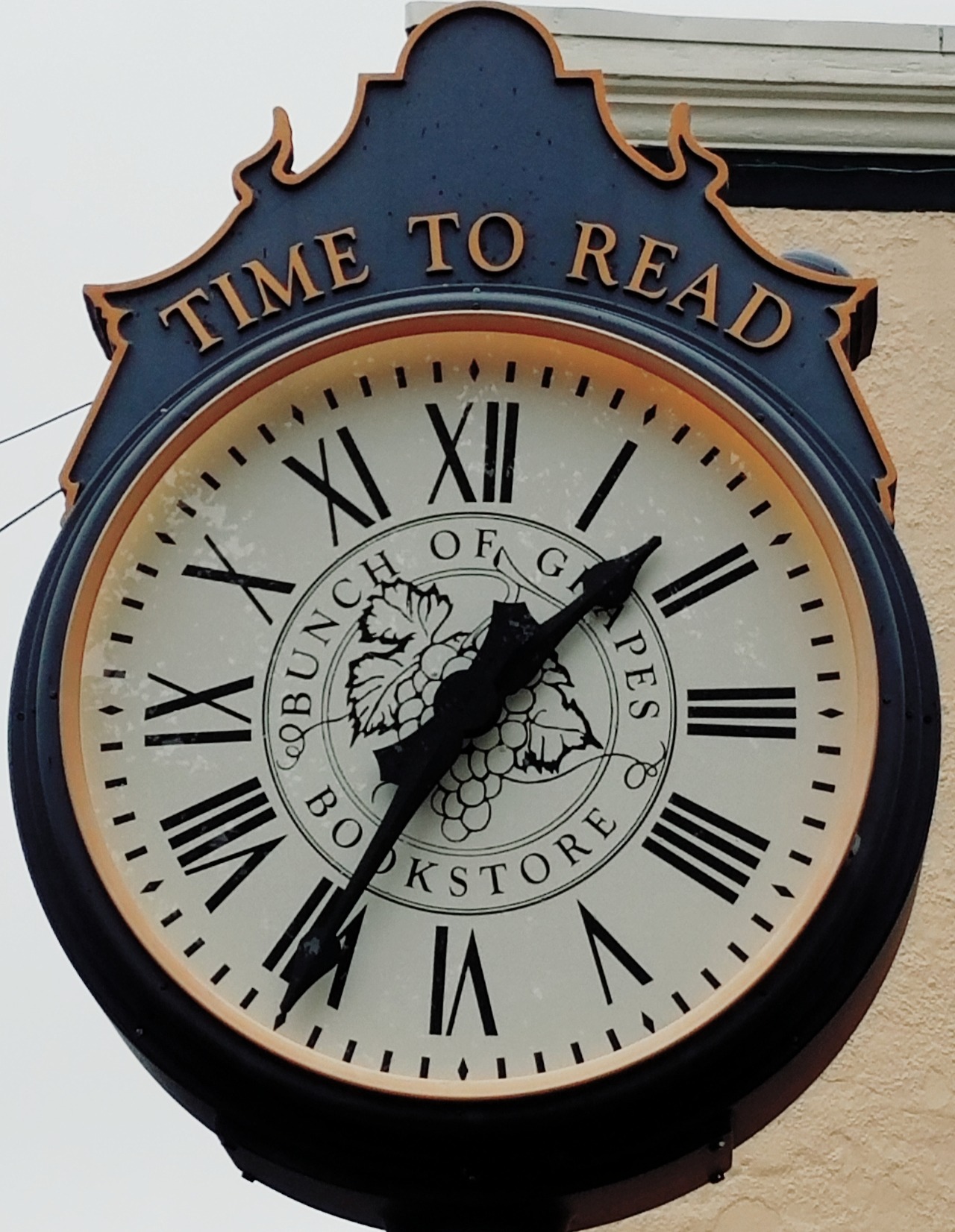

An excellent book ...

Costica Bradatan's reviews ...

To be a respectable scholar today is to specialize in a well-defined, rather narrow subfield, and to stay away from generalist pronouncements. Someone once observed about Leo Strauss that his knowledge was so extraordinary, and covered so many fields, that his colleagues considered him incompetent. Indeed, a reputation for encyclopedism can ruin one’s career. The credo of today’s academic orthodoxy was formulated more than a century ago by Max Weber: “Limitation to specialized work, with a renunciation of the Faustian universality of man which it involves, is a condition of any valuable work in the modern world”. Ironically, Weber was a compulsively Faustian man himself, shuttling between history, law, sociology, philosophy and political theory, among other fields.

That we recognize ourselves in an ancient dispute pitting specialized knowledge against polymathy is no accident. As Peter Burke shows persuasively in The Polymath, the debate has always been part of the West’s self-representation, recurring and amplifying over the centuries, “always the same in essence yet always different in emphases and circumstances”. Whenever we oppose experts to amateurs, theory to practice, pure to applied knowledge, detail to the big picture, we partake in an argument that started in archaic Greece. Burke uses Isaiah Berlin’s distinction between “the fox”, who “knows many things”, and the “hedgehog”, who “knows one great thing”, to emphasize what it is fundamentally at stake.

What has kept the debate alive is that, just as the West has typically valued rigour and expertise, it has at the same time been awed by an ideal of universal knowledge. Heraclitus may have poked fun at the polymath Pythagoras, but his fellow Greeks revered a muse called Polymatheia. A good education in antiquity was enkyklios paideia (which gave us our “encyclopedia”), an ambitious project that demanded the student go through the whole circle of knowledge. Much of our own “liberal arts” education runs along similar lines. People during the Renaissance may have occasionally smiled at Leonardo da Vinci’s unrealistic projects, but they admired him all the same. They could not help recognizing in him the embodiment of an ideal that was only too dear to them, just as it is to us. Dr Faustus was meant to be a dark, repellant figure (“Doctor Fausto, that great sodomite and nigromancer”, noted the deputy Bürgermeister of Nuremberg, in 1532, as he denied the scholar entry to the city), yet he has become one of our paradigmatic heroes. When, about a hundred years ago, Oswald Spengler needed a name to describe what modern Western civilization was essentially about, he came up with the term “Faustian”. We have been calling polymaths names (“amateurs” and “frauds” and worse), and yet we’ve never wanted to be without them.

Bless.

If you don't believe in Jesus, go to hell ... but, may the god of your choice bless you, also.

Happy Birthday, Keats

Horror-struck.

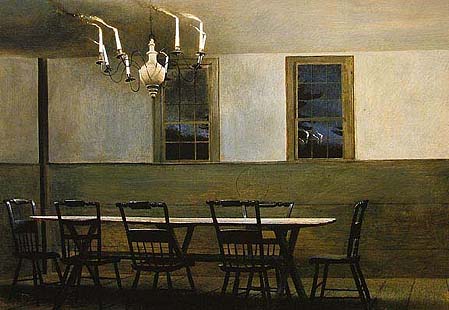

It was the very witching time of night that Ichabod, heavy-hearted and crestfallen, pursued his travels homewards, along the sides of the lofty hills which rise above Tarry Town, and which he had traversed so cheerily in the afternoon. The hour was as dismal as himself. Far below him the Tappan Zee spread its dusky and indistinct waste of waters, with here and there the tall mast of a sloop, riding quietly at anchor under the land. In the dead hush of midnight, he could even hear the barking of the watchdog from the opposite shore of the Hudson; but it was so vague and faint as only to give an idea of his distance from this faithful companion of man. Now and then, too, the long-drawn crowing of a cock, accidentally awakened, would sound far, far off, from some farmhouse away among the hills—but it was like a dreaming sound in his ear. No signs of life occurred near him, but occasionally the melancholy chirp of a cricket, or perhaps the guttural twang of a bullfrog from a neighboring marsh, as if sleeping uncomfortably and turning suddenly in his bed.All the stories of ghosts and goblins that he had heard in the afternoon now came crowding upon his recollection. The night grew darker and darker; the stars seemed to sink deeper in the sky, and driving clouds occasionally hid them from his sight. He had never felt so lonely and dismal. He was, moreover, approaching the very place where many of the scenes of the ghost stories had been laid. In the centre of the road stood an enormous tulip-tree, which towered like a giant above all the other trees of the neighborhood, and formed a kind of landmark. Its limbs were gnarled and fantastic, large enough to form trunks for ordinary trees, twisting down almost to the earth, and rising again into the air. It was connected with the tragical story of the unfortunate André, who had been taken prisoner hard by; and was universally known by the name of Major André’s tree. The common people regarded it with a mixture of respect and superstition, partly out of sympathy for the fate of its ill-starred namesake, and partly from the tales of strange sights, and doleful lamentations, told concerning it.As Ichabod approached this fearful tree, he began to whistle; he thought his whistle was answered; it was but a blast sweeping sharply through the dry branches. As he approached a little nearer, he thought he saw something white, hanging in the midst of the tree: he paused and ceased whistling but, on looking more narrowly, perceived that it was a place where the tree had been scathed by lightning, and the white wood laid bare. Suddenly he heard a groan—his teeth chattered, and his knees smote against the saddle: it was but the rubbing of one huge bough upon another, as they were swayed about by the breeze. He passed the tree in safety, but new perils lay before him.About two hundred yards from the tree, a small brook crossed the road, and ran into a marshy and thickly-wooded glen, known by the name of Wiley’s Swamp. A few rough logs, laid side by side, served for a bridge over this stream. On that side of the road where the brook entered the wood, a group of oaks and chestnuts, matted thick with wild grape-vines, threw a cavernous gloom over it. To pass this bridge was the severest trial. It was at this identical spot that the unfortunate André was captured, and under the covert of those chestnuts and vines were the sturdy yeomen concealed who surprised him. This has ever since been considered a haunted stream, and fearful are the feelings of the schoolboy who has to pass it alone after dark.As he approached the stream, his heart began to thump; he summoned up, however, all his resolution, gave his horse half a score of kicks in the ribs, and attempted to dash briskly across the bridge; but instead of starting forward, the perverse old animal made a lateral movement, and ran broadside against the fence. Ichabod, whose fears increased with the delay, jerked the reins on the other side, and kicked lustily with the contrary foot: it was all in vain; his steed started, it is true, but it was only to plunge to the opposite side of the road into a thicket of brambles and alder bushes. The schoolmaster now bestowed both whip and heel upon the starveling ribs of old Gunpowder, who dashed forward, snuffling and snorting, but came to a stand just by the bridge, with a suddenness that had nearly sent his rider sprawling over his head. Just at this moment a plashy tramp by the side of the bridge caught the sensitive ear of Ichabod. In the dark shadow of the grove, on the margin of the brook, he beheld something huge, misshapen and towering. It stirred not, but seemed gathered up in the gloom, like some gigantic monster ready to spring upon the traveller.The hair of the affrighted pedagogue rose upon his head with terror. What was to be done? To turn and fly was now too late; and besides, what chance was there of escaping ghost or goblin, if such it was, which could ride upon the wings of the wind? Summoning up, therefore, a show of courage, he demanded in stammering accents, “Who are you?” He received no reply. He repeated his demand in a still more agitated voice. Still there was no answer. Once more he cudgelled the sides of the inflexible Gunpowder, and, shutting his eyes, broke forth with involuntary fervor into a psalm tune. Just then the shadowy object of alarm put itself in motion, and with a scramble and a bound stood at once in the middle of the road. Though the night was dark and dismal, yet the form of the unknown might now in some degree be ascertained. He appeared to be a horseman of large dimensions, and mounted on a black horse of powerful frame. He made no offer of molestation or sociability, but kept aloof on one side of the road, jogging along on the blind side of old Gunpowder, who had now got over his fright and waywardness.Ichabod, who had no relish for this strange midnight companion, and bethought himself of the adventure of Brom Bones with the Galloping Hessian, now quickened his steed in hopes of leaving him behind. The stranger, however, quickened his horse to an equal pace. Ichabod pulled up, and fell into a walk, thinking to lag behind,—the other did the same. His heart began to sink within him; he endeavored to resume his psalm tune, but his parched tongue clove to the roof of his mouth, and he could not utter a stave. There was something in the moody and dogged silence of this pertinacious companion that was mysterious and appalling. It was soon fearfully accounted for. On mounting a rising ground, which brought the figure of his fellow-traveller in relief against the sky, gigantic in height, and muffled in a cloak, Ichabod was horror-struck on perceiving that he was headless!—but his horror was still more increased on observing that the head, which should have rested on his shoulders, was carried before him on the pommel of his saddle! His terror rose to desperation; he rained a shower of kicks and blows upon Gunpowder, hoping by a sudden movement to give his companion the slip; but the spectre started full jump with him. Away, then, they dashed through thick and thin; stones flying and sparks flashing at every bound. Ichabod’s flimsy garments fluttered in the air, as he stretched his long lank body away over his horse’s head, in the eagerness of his flight.

Washington Irving, from The Sketchbook of Geoffrey Crayon

30 October 2020

Measure.

29 October 2020

28 October 2020

Happy Birthday, Waugh

Awakened.

Billy Joe Shaver, Rest In Peace

I heard from my friend Kurt today. He told me the sad news that Billy Joe Shaver has passed.

Happy Birthday, Erasmus

Dedicated.

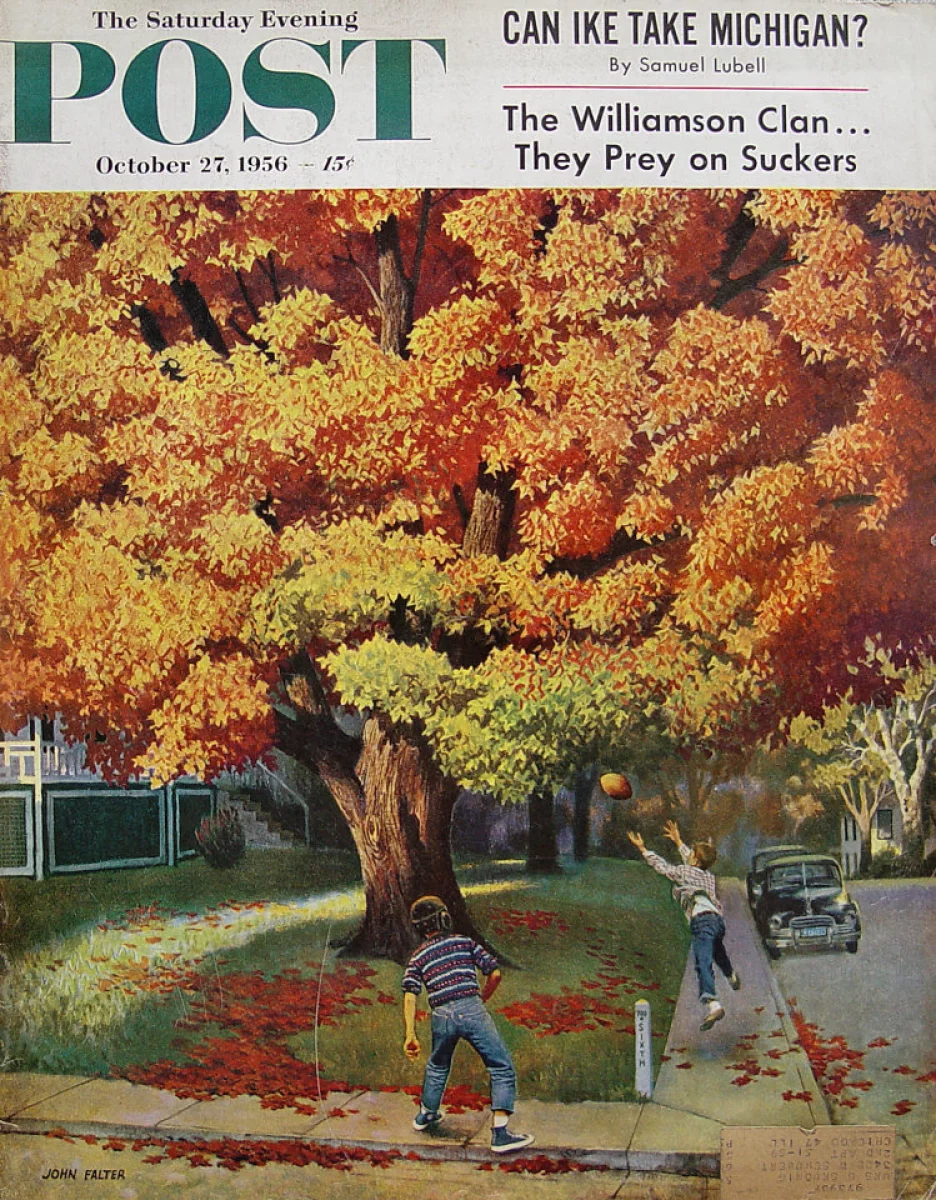

27 October 2020

Happy Birthday, Chatham

Before long, rice and sauce cover the table. Lemon wedges lie scattered about. French bread is torn loose. Each bite of rare, juicy meat is a new thrill, wild duck being something like a cross between filet mignon and fresh deer heart, only with more flavor than either.Our wine glasses become increasingly grease-smeared as we pick up each carcass and suck down to the bare bone and gristle. We carelessly gulp the fancy vintages. Our shirt fronts are ruined. Juice and blood run from elbows on to knees and the floor. The room is blurred. We belch, fart, laugh, and groan.As the carnage winds down I think about my date and wonder if it’s too late, but the face of the clock refuses to come into focus. I find a mirror and what I see there can only be described as soiled.

Wind.

Devotion.

We must show, not merely in great crises, but in the everyday affairs of life, the qualities of practical intelligence, of courage, of hardihood, and endurance, and above all the power of devotion to a lofty ideal, which made great the men who founded this Republic in the days of Washington, which made great the men who preserved this Republic in the days of Abraham Lincoln.

Happy Birthday, Roosevelt

26 October 2020

Hoarsely.

Scarecrow.

Know.

Arrow-heads.

24 October 2020

Adjustments.

In almost every public position in life compromises must be made. The great man is he who makes the minor adjustments—without dishonor—that permit the great issues or important matters to be carried to proper completion.

.jpg)