31 January 2017

Incuriosity.

INTERVIEWER

You are one of the world’s most famous public intellectuals.

How would you define the term intellectual? Does it still have a particular

meaning?

ECO

If by intellectual you mean somebody who works only with his

head and not with his hands, then the bank clerk is an intellectual and

Michelangelo is not. And today, with a computer, everybody is an intellectual.

So I don’t think it has anything to do with someone’s profession or with

someone’s social class. According to me, an intellectual is anyone who is creatively

producing new knowledge. A peasant who understands that a new kind of graft can

produce a new species of apples has at that moment produced an intellectual

activity. Whereas the professor of philosophy who all his life repeats the same

lecture on Heidegger doesn’t amount to an intellectual. Critical

creativity—criticizing what we are doing or inventing better ways of doing

it—is the only mark of the intellectual function.

INTERVIEWER

Are intellectuals today still committed to the notion of

political duty, as they were in the days of Sartre and Foucault?

ECO

I don’t believe that in order to be politically committed an

intellectual must act as a member of a party or, worse, write exclusively about

contemporary social problems. Intellectuals should be as politically engaged as

any other citizen. At most, an intellectual can use his reputation to support a

given cause. If there is a manifesto on the environmental question, for

instance, my signature might help, so I would use my reputation for a single instance

of common engagement. The problem is that the intellectual is truly useful only

as far as the future is concerned, not the present. If you are in a theater and

there is a fire, a poet must not climb up on a seat and recite a poem. He has

to call the fireman like everyone else. The function of the intellectual is to

say beforehand, Pay attention to that theater because it’s old and dangerous!

So his word can have the prophetic function of an appeal. The intellectual’s

function is to say, We should do that, not, We must do this now!—that’s the

politician’s job. If the utopia of Thomas More were ever realized, I have

little doubt it would be a Stalinist society.

INTERVIEWER

What benefits have knowledge and culture afforded you in

your lifetime?

ECO

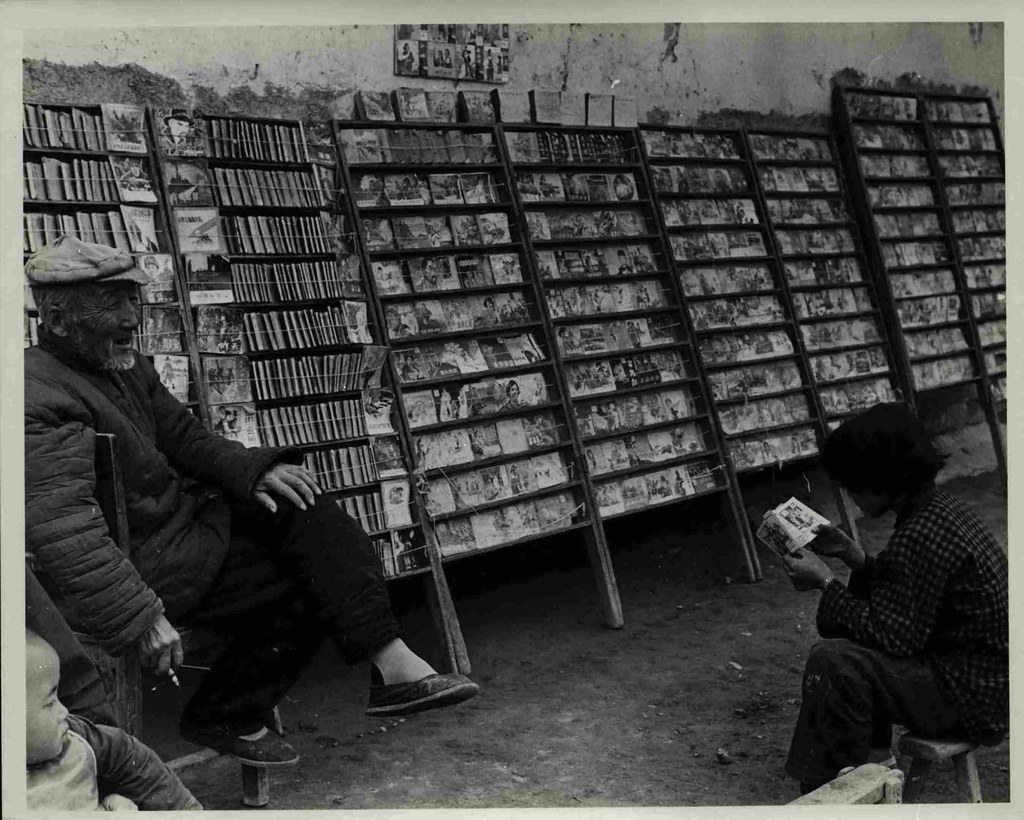

An illiterate person who dies, let us say at my age, has

lived one life, whereas I have lived the lives of Napoleon, Caesar, d’Artagnan.

So I always encourage young people to read books, because it’s an ideal way to

develop a great memory and a ravenous multiple personality. And then at the end

of your life you have lived countless lives, which is a fabulous privilege.

INTERVIEWER

But an enormous memory can also be an enormous burden. Like

the memory of Funes, one of your favorite Borges characters, in the story

“Funes the Memorious.”

ECO

I like the notion of stubborn incuriosity. To cultivate a stubborn incuriosity, you have to limit yourself to certain areas of knowledge. You cannot be totally greedy. You have to oblige yourself not to learn everything. Or else you will learn nothing. Culture in this sense is about knowing how to forget. Otherwise, one indeed becomes like Funes, who remembers all the leaves of the tree he saw thirty years ago. Discriminating what you want to learn and remember is critical from a cognitive standpoint.

I like the notion of stubborn incuriosity. To cultivate a stubborn incuriosity, you have to limit yourself to certain areas of knowledge. You cannot be totally greedy. You have to oblige yourself not to learn everything. Or else you will learn nothing. Culture in this sense is about knowing how to forget. Otherwise, one indeed becomes like Funes, who remembers all the leaves of the tree he saw thirty years ago. Discriminating what you want to learn and remember is critical from a cognitive standpoint.

Beethoven, Piano Trio in D major, Op. 70, No. 1, "Ghost"

This performance features Daniel Barenboim and his red jacket, piano, Pinchas Zukerman, violin, and Jacqueline du Pré, cello ...

Happy birthday, Merton.

Thomas Merton was born on this day in 1915.

Do not depend on the hope of results. You may have to face

the fact that your work will be apparently worthless and even achieve no result

at all, if not perhaps results opposite to what you expect. As you get used to

this idea, you start more and more to concentrate not on the results, but on

the value, the rightness, the truth of the work itself. You gradually struggle

less and less for an idea and more and more for specific people. In the end, it

is the reality of personal relationship that saves everything.

Thomas Merton

30 January 2017

29 January 2017

Wanderers.

We wanderers, ever seeking the lonelier way, begin no day

where we have ended another day; and no sunrise finds us where sunset left us.

Even while the earth sleeps we travel. We are the seeds of the tenacious plant,

and it is in our ripeness and our fullness of heart that we are given to the

wind and are scattered.

Kahlil Gibran

Vivaldi, Flute Concerto in G minor, RV 439, "La Notte"

Ensemble Imaginarium performs under the direction of Enrico Onofri, featuring Marco Brolli, traverse flute ...

Steam.

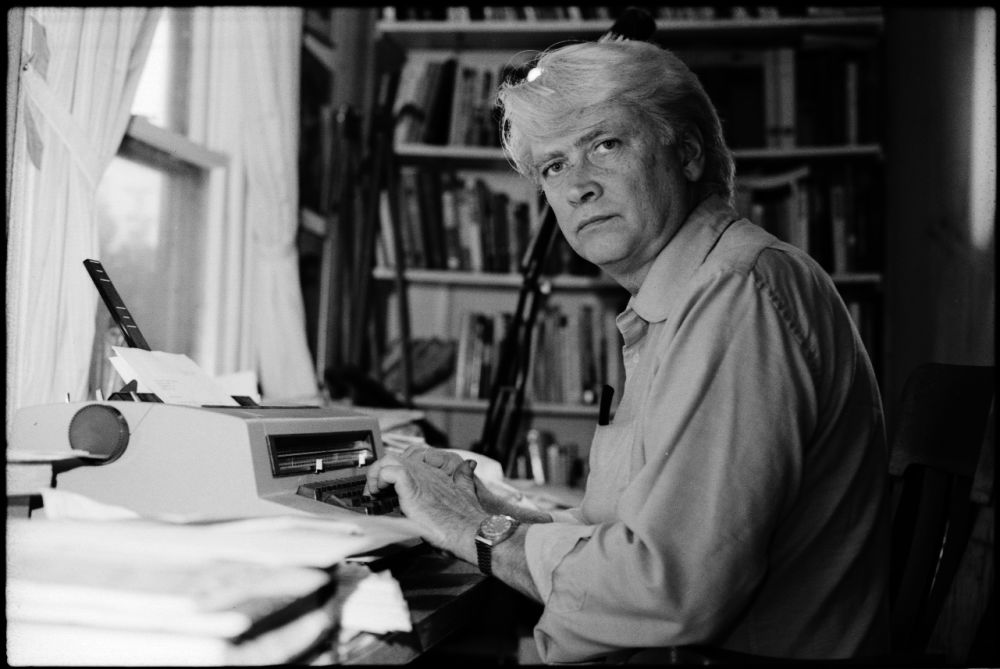

From John Garner, "The Art of Fiction," No. 73 ...

INTERVIEWER

INTERVIEWER

Do you feel that literary techniques can really be taught?

Some people feel that technique is an artifice or even a hindrance to “true

expression.”

GARDNER

Certainly it can be taught. But a teacher has to know technique

to teach it. I've seen a lot of writing teachers because I go around visiting

colleges, visiting creative writing classes. A terrible number of awful ones,

grotesquely bad. That doesn't mean that one should throw writing out of the

curriculum; because when you get a good creative writing class it's

magisterial. Most of the writers I know in the world don't know how they do

what they do. Most of them feel it out. Bernard Malamud and I had a

conversation one time in which he said that he doesn't know how he does those

magnificent things he sometimes does. He just keeps writing until it comes out

right. If that's the way a writer works, then that's the way he had to work,

and that's fine. But I like to be in control as much of the time as possible. One

of the first things you have to understand when you are writing fiction—or

teaching writing—is that there are different ways of doing things, and each one

has a slightly different effect. A misunderstanding of this leads you to the

Bill Gass position: that fiction can't tell the truth, because every way you

say the thing changes it. I don't think that's to the point. I think that what

fiction does is sneak up on the truth by telling it six different ways and

finally releasing it. That's what Dante said, that you can't really get at the

poetic, inexpressible truths, that the way things are leaps up like steam

between them. So you have to determine very accurately the potential of a

particular writer's style and help that potential develop at the same time, ignoring

what you think of his moral stands.

I hate nihilistic, cynical writing. I hate it. It bothers

me, and worse yet, bores me. But if I have a student who writes with morbid

delight about murder, what I'll have to do (though of course I'll tell him I don't

like this kind of writing, that it's immoral, stupid, and bad for

civilization), is say what is successful about the work and what is not. I have

to swallow every bit of my moral feelings to help the writer write his way, his

truth. It may be that the most moral writing of all is writing that shows us

how a murderer feels, how it happens. It may be it will protect us from

murderers someday.

Pathways.

We should not force ourselves to change by hammering our

lives into any predetermined shape. We do not need to operate according to the

idea of a predetermined program or plan for our lives. Rather, we need

to practice a new art of attention to our inner rhythm of our days

and lives. This attention brings a new awareness of our own human and divine

presence. A dramatic example of this kind of transfiguration is the one all

parents know. You watch your children carefully, but one day they surprise you;

you still recognize them, but your knowledge of them is insufficient.

You have to start listening to them all over again.

It is far more creative to work with the idea of mindfulness

rather than with the idea of will. Too often people try to change their lives

by using the will as a kind of hammer to beat their life into proper shape. The

intellect identifies the goal of the program, and the will accordingly forces

the life into that shape. This way of approaching the sacredness of one’s own

presence is externalistic and violent. It brings you falsely outside your own

self and you can spend years lost in the wilderness of your own mechanical,

spiritual programs. You can perish in a famine of your own making.

If you work with a different rhythm, you will come easily

and naturally home to your self. Your soul knows the geography of your destiny.

Your soul alone has a map of your future, therefore you can trust this

indirect, oblique side of your self. If you do, it will take you where you need

to go, but more importantly it will teach you a kindness of rhythm in your

journey. There are no general principles for this art of being. Yet the

signature of this unique journey is inscribed deeply in each soul. If you

attend to your self and seek to come into your own presence, you will find

exactly the right rhythm for your life. The senses are generous pathways which

can bring you home.

John O’Donohue

Kings.

Eisenstaedt, Children at a Puppet Show, Paris, 1963

In a world where nearly everything that passes for art is

tinny and commercial and often, in addition, hollow and academic, I argue -- by

reason and by banging the table -- for an old-fashioned view of what art is and

does and what the fundamental business of critics ought therefore to be. Not

that I want joy taken out of the arts; but even frothy entertainment is not

harmed by a touch of moral responsibility, at least an evasion of too

fashionable simplifications.

We need to stop excusing mediocre and downright pernicious

art, stop "taking it for what it’s worth" as we take our fast foods, our

overpriced cars that are no good, the overpriced houses we spend all our lives

fixing, our television programs, our schools thrown up like barricades in the

way of young minds, our brainless fat religions, our poisonous air, our

incredible cult of sports, and our ritual of fornicating with all pretty or

even horse-faced strangers. We would not put up with a debauched king, but in a

democracy all of us are kings, and we praise debauchery as pluralism.

John C. Gardner

28 January 2017

Resilience.

In the mid-1800s, a railroad director, entrepreneur, and

politician named Lewis Henry Morgan began visiting a largely undeveloped swath

of land dotted with beaver ponds in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. What he saw

amazed him: “[A] beaver district, more remarkable, perhaps, than any other of

equal extent to be found in any part of North America,” he wrote. “A rare

opportunity was thus offered to examine the works of the beaver, and to see him

in his native wilds.”

Morgan wasn’t your typical nature buff. His pioneering

anthropological studies of Native American tribes had already begun to

make him an enormously influential figure in 19th century science. In 1880, he

would be elected president of AAAS (publisher of Science), and

Charles Darwin, Sigmund Freud, and Karl Marx would come to cite his work. But

as Morgan helped his railroad company lay tracks across the Michigan wilderness

in the 1850s and 1860s, the target of his scientific curiosity was the North

American beaver (Castor canadensis).

For years, he carefully documented how the beavers behaved

and where they built their dams and ponds. Then, in 1868, Morgan published his

396-page beaver bible: The American Beaver and His Works. Folded into each

copy was a map, carefully drawn by his railroad’s engineers, which detailed the

locations of 64 beaver dams and ponds spread over some 125 square kilometers

near the community of Ishpeming.

Now, that rare map is giving researchers some new insight

into just how busy beavers can be. A new survey shows that many of the dams and

ponds that Morgan saw nearly 150 years ago are still there—testament to the

resilience of the rodents and their ability to maintain structures over many

generations.

CONNECT

Feels.

BACCHANALIA

I

The evening comes, the fields are still.

The tinkle of the thirsty rill,

Unheard all day, ascends again;

Deserted is the half-mown plain,

Silent the swaths! the ringing wain,

The mower's cry, the dog's alarms,

All housed within the sleeping farms!

The business of the day is done,

The last-left haymaker is gone.

And from the thyme upon the height,

And from the elder-blossom white

And pale dog-roses in the hedge,

And from the mint-plant in the sedge,

In puffs of balm the night-air blows

The perfume which the day forgoes.

And on the pure horizon far,

See, pulsing with the first-born star,

The liquid sky above the hill!

The evening comes, the fields are still.

Loitering and leaping,

With saunter, with

bounds—

Flickering and circling

In files and in rounds—

Gaily their pine-staff

green

Tossing in air,

Loose o'er their

shoulders white

Showering their hair—

See! the wild Maenads

Break from the wood,

Youth and Iacchus

Maddening their blood.

See! through the quiet

land

Rioting they pass—

Fling the fresh heaps

about,

Trample the grass.

Tear from the rifled

hedge

Garlands, their prize;

Fill with their sports

the field,

Fill with their cries.

Shepherd, what ails

thee, then?

Shepherd, why mute?

Forth with thy joyous

song!

Forth with thy flute!

Tempts not the revel

blithe?

Lure not their cries?

Glow not their

shoulders smooth?

Melt not their eyes?

Is not, on cheeks like

those,

Lovely the flush?

—Ah, so the quiet

was!

So was the hush!

II

The epoch ends, the world is still.

The age has talk'd and work'd its fill—

The famous orators have shone,

The famous poets sung and gone,

The famous men of war have fought,

The famous speculators thought,

The famous players, sculptors, wrought,

The famous painters fill'd their wall,

The famous critics judged it all.

The combatants are parted now—

Uphung the spear, unbent the bow,

The puissant crown'd, the weak laid low.

And in the after-silence sweet,

Now strifes are hush'd, our ears doth meet,

Ascending pure, the bell-like fame

Of this or that down-trodden name,

Delicate spirits, push'd away

In the hot press of the noon-day.

And o'er the plain, where the dead age

Did its now silent warfare wage—

O'er that wide plain, now wrapt in gloom,

Where many a splendour finds its tomb,

Many spent fames and fallen mights—

The one or two immortal lights

Rise slowly up into the sky

To shine there everlastingly,

Like stars over the bounding hill.

The epoch ends, the world is still.

Thundering and bursting

In torrents, in waves—

Carolling and shouting

Over tombs, amid

graves—

See! on the cumber'd

plain

Clearing a stage,

Scattering the past

about,

Comes the new age.

Bards make new poems,

Thinkers new schools,

Statesmen new systems,

Critics new rules.

All things begin again;

Life is their prize;

Earth with their deeds

they fill,

Fill with their cries.

Poet, what ails thee,

then?

Say, why so mute?

Forth with thy praising

voice!

Forth with thy flute!

Loiterer! why sittest

thou

Sunk in thy dream?

Tempts not the bright

new age?

Shines not its stream?

Look, ah, what genius,

Art, science, wit!

Soldiers like Caesar,

Statesmen like Pitt!

Sculptors like Phidias,

Raphaels in shoals,

Poets like Shakespeare—

Beautiful souls!

See, on their glowing

cheeks

Heavenly the flush!

—Ah, so the

silence was!

So was the hush!

The world but feels the present's spell,

The poet feels the past as well;

Whatever men have done, might do,

Whatever thought, might think it too.

Teaches.

Chef Marco Pierre White on teaches about persistence, simplicity, and remembering origins ...

27 January 2017

Died.

A wonderful thing happens when you give up on hope, which is

that you realize you never needed it in the first place. You realize that

giving up on hope didn’t kill you. It didn’t even make you less effective. In

fact it made you more effective, because you ceased relying on someone or

something else to solve your problems — you ceased hoping your

problems would somehow get solved through the magical assistance of God, the

Great Mother, the Sierra Club, valiant tree-sitters, brave salmon, or even the

Earth itself — and you just began doing whatever it takes to solve those

problems yourself.

When you give up on hope, something even better happens than

it not killing you, which is that in some sense it does kill you. You die. And

there’s a wonderful thing about being dead, which is that they — those in power

— cannot really touch you anymore. Not through promises, not through threats,

not through violence itself. Once you’re dead in this way, you can still sing,

you can still dance, you can still make love, you can still fight like hell —

you can still live because you are still alive, more alive in fact than ever

before. You come to realize that when hope died, the you who died with the hope

was not you, but was the you who depended on those who exploit you, the you who

believed that those who exploit you will somehow stop on their own, the you who

believed in the mythologies propagated by those who exploit you in order to

facilitate that exploitation. The socially constructed you died. The civilized

you died. The manufactured, fabricated, stamped, molded you died. The victim died.

Derrick Jensen

Doors.

Those for whom culture has been a long-term emotional

investment feel they know what true culture is, and know that it is a thing of

supreme value. But when we try to define it we end up like the poet Matthew

Arnold who, in a celebrated essay, Culture and Anarchy, published in 1865,

wrote of culture as “the best that has been thought and said.” To which the

obvious response is: in what respect and in comparison with what? And what’s

wrong with second best?

We cannot lay down a law for popular taste or forbid people

to enjoy what appeals to them – not unless we can find some serious moral

argument that would justify censorship. But there are certain general

principles that everyone can assent to. For example, we all recognise the

difference between means and ends. We know that we choose the means to our

ends, but also that we choose our ends. We are active guardians of our own

lives, aiming not just to hit the target that we have chosen, but also to

choose the right target. How do we learn to do that? The answer is culture –

both the culture of everyday life and the “high” culture, as it is sometimes

called, in which life becomes fully conscious of itself as an object of

judgment. The arts form the core of high culture: it is why we teach them, and

why we encourage people to take an interest in them. They are doors into the

examined life and, as Socrates famously said, “the unexamined life is not a

life for a human being.”

Roger Scruton

Roger Scruton

Must.

There may be times when we are powerless to prevent

injustice, but there must never be a time when we fail to protest. We must take sides. Neutrality helps

the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the

tormented. Sometimes we must interfere. When human lives are endangered, when

human dignity is in jeopardy, national borders and sensitivities become

irrelevant. Wherever men and women are persecuted because of their race,

religion, or political views, that place must - at that moment - become the

center of the universe.

Elie Wiesel

Happy birthday, Mozart.

Lange, Mozart, 1782

Johannes Chrysostomus Wolfgangus Theophilus Mozart was born on this day in 1756.

Whoever is most impertinent has the best chance.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Whoever is most impertinent has the best chance.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Sir Colin Davis leads the Bayerischen Rundfunks Symphony Orchestra in the Serenade No. 10 in B-flat major, K.361/370a, "Gran Partita" ...

25 January 2017

24 January 2017

23 January 2017

Happy birthday, Manet.

Manet, A Bouquet of Flowers, 1889

Edouard Manet was born on this day in 1832.

It is not enough to know your craft – you have to have feeling. Science is all very well, but for us imagination is worth far more.

Edouard Manet

Manet: The Man Who Invented Modern Art, a documentary by Waldemar Januszczak ...

22 January 2017

21 January 2017

Safeguard.

Why does the state take an interest in education? The prevailing view, at least since the end of the last war, has been that the state takes an interest in education because it is the right of every child to receive it. Hence the state becomes the universal provider, and as such must treat all its dependents equally, and make no special favours on grounds of wealth, talent or social status.

From this, by a kind of creeping egalitarianism, we edge towards the conclusion that the state must make no distinctions, that children should not be sorted by their abilities and aptitudes, and that even exams should be downgraded or at least not made to look as though they were the final goal. When it comes to schooling, the educationists add, we, the experts, are bound to be better informed than the parents, who should feel no qualms in surrendering their children to the beneficent care of a state that acts always on our wise advice.

The assumption has been, in other words, that education exists for the sake of the child. In my view the state takes an interest in education only because it has another and more urgent interest in something else — namely knowledge. Knowledge is a benefit to everyone, including those who do not and cannot acquire it. How many of our citizens could build a nuclear power station, judge a case in Chancery, read a grant of land in mediaeval Latin, conduct a Mozart concerto, solve an equation in aerodynamics, repair a railway engine? We don’t need to have the knowledge ourselves, provided there are others, the experts, who possess it. And the more we outsource our memory and information to our iPhones and laptops, the more those experts are needed. If that is so, then the state must ensure that education, however available and however distributed, will reproduce our store of knowledge, and if possible add to it.

There may come a time when children and their teachers cease to hear about the Dark Ages. People may then no longer understand that knowledge can be lost as well as gained, as our store of knowledge was lost for 400 years, before being slowly and painfully recuperated. Here, it seems to me, is where the educationists have misled us. The state, they have told us, has a duty towards each child, and no child must be made to feel inferior to any other. Although that is true, the state has another and greater duty which is a duty towards us all — namely, the duty to conserve the knowledge that we need, which can be passed on only with the help of the children able to acquire it.

To put the matter simply, knowledge benefits the child, but not as much as the clever child benefits knowledge. Hence the state has an interest in selection, so that those with an aptitude for knowledge can be given the chance to acquire it — to acquire it without the many distractions that come from being surrounded by others who have no interest in the life of the mind.

I was fortunate to attend a grammar school, which made available to me the kind of knowledge that people of my parents’ class did not easily have the chance to acquire. Hence I have played my own special part in absorbing, processing and passing on the knowledge that is still enshrined in our curriculum. I take this as a justification for my existence, that I have passed on to others something that, but for the kind of education I enjoyed, might have died.

Critics tell us that selection divides children into successes and failures, and that the failures are ‘marked for life’. I see no reason to believe that. Future generations need knowledge; but they also need skills, strengths and technical know-how. Schools that provide those benefits — like the German Technische Hochschulen — are as important as grammar schools: and if children have the possibility of freely passing between schools in the process of discovering their aptitude, then selection need in any case never be final.

In the world of education those thoughts are heresies. After years of ‘child-centred’ indoctrination the educational establishment has become lost in a kind of fairyland, believing that education is really a form of social engineering, and that its primary purpose is to boost the pupil’s ‘self-esteem’. Once we see that the primary purpose of education is to safeguard knowledge, all the fairy castles of the educationists tumble in ruins. Hence they are up in arms, and, as so often, in arms against the truth.

Roger Scruton

20 January 2017

Gordon Lightfoot, "Early Morning Rain"

I'm a long way from home

Lord, I miss my loved ones so

In the early morning rain

With no place to go

19 January 2017

Leads.

Some people, I am told, have memories like computers,

nothing to do but punch the button and wait for the print-out. Mine is more

like a Japanese library of the old style, without a card file or an indexing

system or any systematic shelf plan. Nobody knows where anything is except the

old geezer in felt slippers who has been shuffling up and down those stacks for

sixty-nine years. When you hand him a problem he doesn't come back with a

cartful and dump it before you, a jackpot of instant retrieval. He finds one

thing, which reminds him of another, which leads him off to the annex, which

directs him to the east wing, which sends him back two tiers from where he

started. Bit by bit he finds you what you want, but like his boss who seems to

be under pressure to examine his life, he takes his time.

Wallace Stegner

Better.

van Gogh, The Mulberry Tree, 1889

Surely a canvas I've covered is worth more than a blank one.

This, dear Lord is all I have -- my right to paint, my reason for painting --

and believe me, my pretensions go no further.

And after all it has cost me: this dilapidated carcass and a brain addled from living as best I can and have had to because of my own philanthropy.

My concentration is becoming more intense, my touch more certain. So I can almost dare to promise you that my paintings will get better. Because that is all I have left.

And after all it has cost me: this dilapidated carcass and a brain addled from living as best I can and have had to because of my own philanthropy.

My concentration is becoming more intense, my touch more certain. So I can almost dare to promise you that my paintings will get better. Because that is all I have left.

Vincent Van Gogh

18 January 2017

Making.

Witkiewicz, Jesieniowiska, 1894

The best teachers have showed me that things have to be done

bit by bit. Nothing that means anything happens quickly--we only think it does.

The motion of drawing back a bow and sending an arrow straight into a target

takes only a split second, but it is a skill many years in the making. So it is

with a life, anyone's life. I may list things that might be described as my

accomplishments in these few pages, but they are only shadows of the larger

truth, fragments separated from the whole cycle of becoming. And if I can tell

an old-time story now about a man who is walking about, a forest lodge man, it

is because I spent many years walking about myself, listening to voices that

came not just from the people but from animals and trees and stones.

Joseph Brochak

17 January 2017

Dvořák, Symphony No. 9 in E Minor, "New World"

The Largo performed by the Vienna Philharmonic, directed by Herbert von Karajan ...

This.

You may have noticed that the books you really love are bound together by a secret thread. You know very well what is the common quality that makes you love them, though you cannot put it into words: but most of your friends do not see it at all, and often wonder why, liking this, you should also like that. Again, you have stood before some landscape, which seems to embody what you have been looking for all your life; and then turned to the friend at your side who appears to be seeing what you saw — but at the first words a gulf yawns between you, and you realize that this landscape means something totally different to him, that he is pursuing an alien vision and cares nothing for the ineffable suggestion by which you are transported. Even in your hobbies, has there not always been some secret attraction which the others are curiously ignorant of — something, not to be identified with, but always on the verge of breaking through, the smell of cut wood in the workshop or the clap-clap of water against the boat’s side? Are not all lifelong friendships born at the moment when at last you meet another human being who has some inkling (but faint and uncertain even in the best) of that something which you were born desiring, and which, beneath the flux of other desires and in all the momentary silences between the louder passions, night and day, year by year, from childhood to old age, you are looking for, watching for, listening for? You have never had it. All the things that have ever deeply possessed your soul have been but hints of it — tantalizing glimpses, promises never quite fulfilled, echoes that died away just as they caught your ear. But if it should really become manifest — if there ever came an echo that did not die away but swelled into the sound itself — you would know it. Beyond all possibility of doubt you would say,“Here at last is the thing I was made for." We cannot tell each other about it. It is the secret signature of each soul, the incommunicable and unappeasable want, the thing we desired before we met our wives or made our friends or chose our work, and which we shall still desire on our deathbeds, when the mind no longer knows wife or friend or work. While we are, this is. If we lose this, we lose all.

C.S. Lewis

Revealed.

Roger Scruton

A section of Scruton's talk, "The View from Nowhere," which was part of the Gifford Lectures' The Face of God ...

16 January 2017

Poetry.

Cuvelier, Fountainebleau Forest, 1869

How I used to love the dark, sad evenings of late autumn and winter, how eagerly I imbibed their moods of loneliness and melancholy when wrapped in my cloak I strode for half the night through rain and storm, through the leafless winter landscape, lonely enough then too, but full of deep joy, and full of poetry.

How I used to love the dark, sad evenings of late autumn and winter, how eagerly I imbibed their moods of loneliness and melancholy when wrapped in my cloak I strode for half the night through rain and storm, through the leafless winter landscape, lonely enough then too, but full of deep joy, and full of poetry.

Herman Hesse

Himself.

Jean Piaget

Lessons.

CONNECT

Own.

Human freedom is finite freedom. Man is not free from

conditions. But he is free to take a stand in regard to them. The conditions do

not completely condition him. Although our existence is influenced by

instincts, inherited disposition and environment, an area of freedom is always

available to us. Everything can be taken from a man, but the last of the human

freedoms is to choose one’s attitude in any a given set of circumstances, to

choose one’s own way.

Dr. Viktor Frankel

Dr. Viktor Frankel