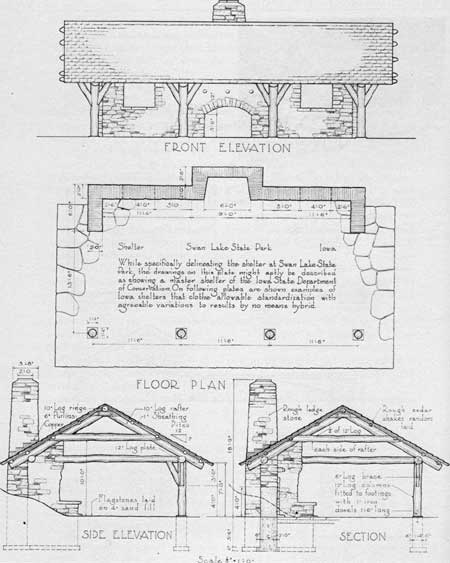

For lack of a better phrase, these varied styles have long been inadequately lumped together under the term "rustic architecture." But perhaps a voice from the 1930s can explain the problem more clearly:

"The style of architecture which has been most widely used in our forested National Parks, and other wilderness parks, is generally referred to as "rustic. " It is, or should be, something more than the worn and misused term implies. It is earnestly hoped that a more apt and expressive designation for the style may evolve, but until it appears, "rustic, " in spite of its inaccuracy and inadequacy, must beA superior term has never appeared, so "rustic" it remains.

resorted to . . . . "

CONNECT

No comments:

Post a Comment