McGuane has lived on Montana ranches for almost as long as he’s been a published writer, and the processes of maintenance and improvement feature frequently in his fiction and nonfiction. In Nobody’s Angel (1981), the troubled and aimless protagonist has only his horsemanship as bedrock: “Patrick used spurs like a pointing finger, pressing movement into a shape, never striking or gouging. And horseback, unlike any other area of his life, he never lost his temper, which, in horsemen, is the final mark of the amateur.” Some Horses (1999), a nonfiction look at training, using, and competing with cattle-ranching horses (known as cutting horses), contains some of McGuane’s most meticulously descriptive and effortlessly analogic writing, in which the lessons of horse riding seem to stand in for lessons of life.

“A cutting horse not only has to be quicker than the cow but also has to have the strategic sense to deal with the cow’s bold first moves. The rider, through weight shifts and other body signals (such as leg pressure and touches of the spurs), can tell the horse what he thinks the cow will do. The rider must also react without interference to moves the horse devises on his own. These shared signals constitute the elusive ‘feel’ of cutting.”

And McGuane is not unaware of connections between properly learned process or technique and proper living:

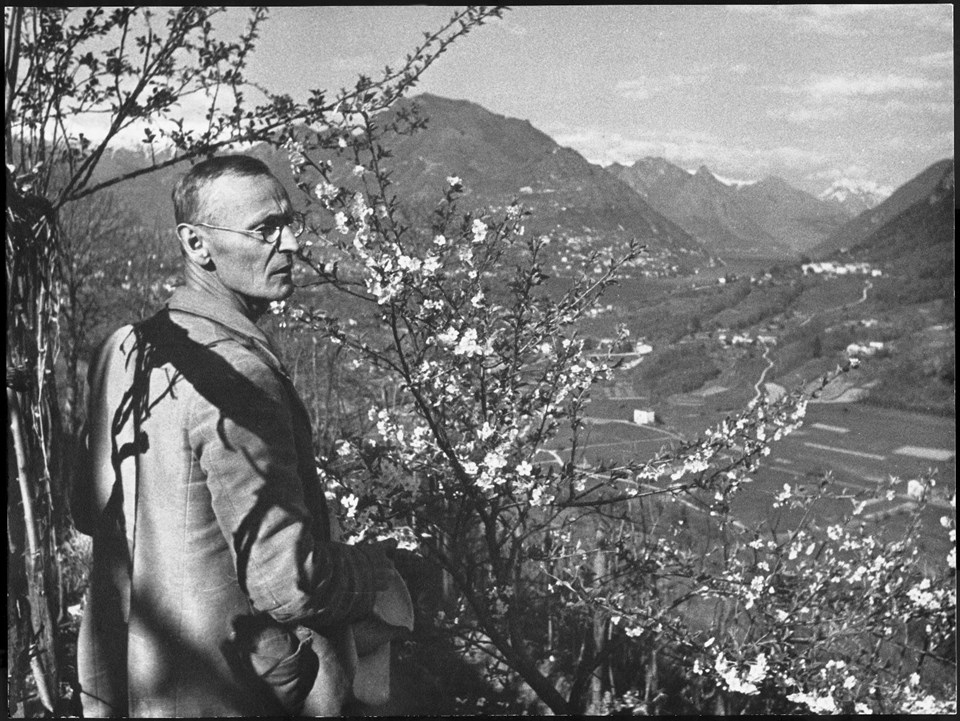

"I once gave Eugen Herrigel’s little masterpiece Zen in the Art of Archery to Buster [a famed cutting-horse trainer] to read and he concluded that its application to horsemanship was that if you are thinking about your riding you are interfering with your horse."

Process (“doingness”) mastered to this extent comes to feel analogous not only to proper living but to proper writing, and McGuane’s approach does seem to include an element of Zenlike dedication to writing as process, or at least a workerlike dedication to putting in the hours. About his writing apprenticeship he has this to say: “I thought that if you didn’t work at least as hard as the guy who runs a gas station then you had no right to hope for achievement. You certainly had to work all day, every day. I thought that was the deal. I still think that’s the deal.”

McGuane has never been a proponent of the easy answer. A fish moving by “force of blood” may be “exactly noble,” but people get no such pass. At best, they achieve a craftsman’s expertise—guiding, riding, fishing. And expertise is a guarantee only of itself. Wider knowledge or continued growth may not be in the cards. “The bonefisherman has a mildly scientific proclivity for natural phenomenology insofar as it applies to his quest, but unfortunately he is inclined to regard a flock of roseate spoonbills only in terms of flying objects liable to spook fish.” A writer’s style—a similarly practicable craft in McGuane’s world—holds no promise of ongoing improvement. Michael Wood, in his introduction to On Late Style, points out that it “can’t be a direct result of aging or death, because style is not a mortal creature, and works of art have no organic life to lose.” Style does not grow, like a plant, based on soil and rainfall, or like a fish or a horse, based on breeding and instinct and environment. It is a willed thing.

Read the rest here.

No comments:

Post a Comment